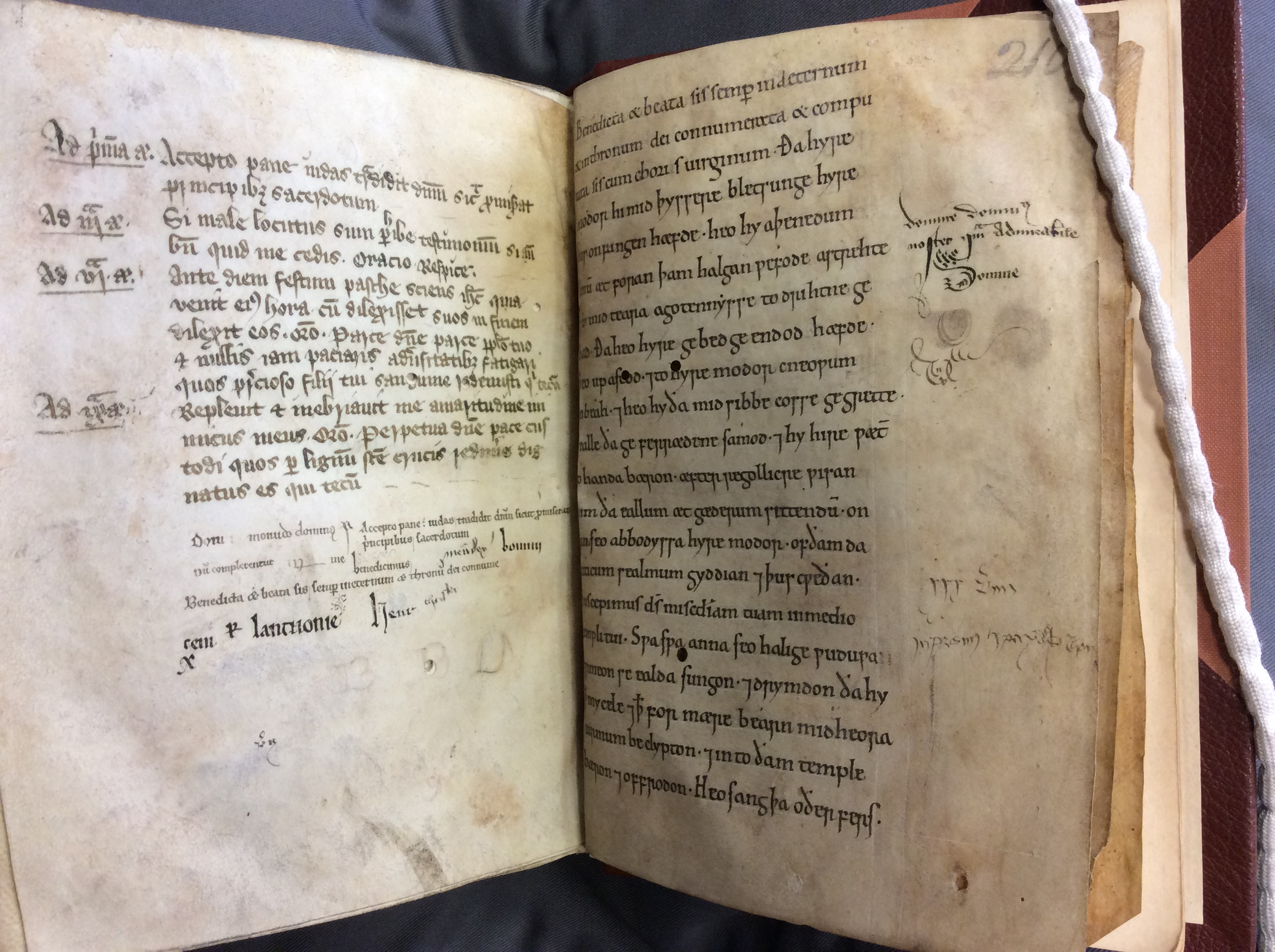

London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427, fols.209v-210r. Reproduced with the kind permission of Lambeth Palace Library. Note the first line of fol.210r is copied in a pen trial on fol. 209v. Fols. 210 and 211 were are one stage used as binding, but worm holes through the vellum indicate that the leaves have long been incorporated into the manuscript proper.

London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427, fols.209v-210r. Reproduced with the kind permission of Lambeth Palace Library. Note the first line of fol.210r is copied in a pen trial on fol. 209v. Fols. 210 and 211 were are one stage used as binding, but worm holes through the vellum indicate that the leaves have long been incorporated into the manuscript proper.

by Diane Watt

Most of the early medieval texts at which I am looking as part of the project ‘Women’s Literary Culture Before the Conquest’ are in Latin, produced by or for women religious. The evidence for female authorship or a specifically female audience of Old English poetry and prose is sparse, although of course the female-voiced Old English elegies ‘Wulf and Eadwacer’ and ‘The Wife’s Lament’, both found in the tenth century Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library, Exeter Dean and Chapter MS 3501) may be an exception. This depends, however, on whether or not we accept that they fall within the tradition of frauenlied [women’s song] and that they might have been composed either by a woman or with women in mind. Women would certainly have encountered other works, including sermons and saints’ lives, and some of these texts (such as some of Ælfric’s late tenth-century homilies) address female readers either directly or implicitly.

A major feature of much Old English Literature is that it is fragmentary. The famous Old English poem Judith (composed in the late tenth century or early eleventh), which is found alongside Beowulf in London, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A. XV , is famously incomplete. According to R. M. Liuzza, in his introduction to the volume Old English Literature: Critical Essays:

The surviving remains of Old English literature are the flotsam and jetsam of a vanished world, manuscripts and fragments of texts divorced from their original context, most of them second- or third hand copies of unknown originals, many of them saved from oblivion only by chance or neglect. From these randomly preserved parts of a whole we are supposed to extrapolate a fluid and living system—a spoken dialect, a literary tradition, a moment in history—but it is sometimes difficult to imagine how to move from these discontinuous scraps to a reconstructed reality. (p.xi)

Given such a fragmented and often anonymous body of work, Liuzza goes on to ask ‘Can we make these texts speak?’ This is the question that I want to address in this post, specifically in relation to the possibility of female authorship lying behind three Old English fragmentary lives of or associated with Mildrith, the eighth-century abbess of Minster-in-Thanet in Kent. M.J. Swanton edited and translated these three fragmentary texts in ‘A Fragmentary Life of St. Mildred and other Kentish Royal Saints’, Archæologia Cantiana 91 (1975): 15-27.

As David W. Rollason explains in his study of the legend of Mildrith (which exists in a number of versions, including three Latin lives), it most likely dates to the time of Mildrith’s successor, Eadburg of Minster-in-Thanet, who translated Mildrith’s remains and fostered her cult. Eadburg probably commissioned the writing down of the earliest version of this legend, or she may have written it herself. Stephanie Hollis, in her 2008 article ‘The Minster-in-Thanet Foundation Story’, makes the case for an Old English Mildrith tradition ‘created by monastic women’ and argues that the main function of the legend of St Mildrith was ‘commemoration of the founder-abbess of Thanet and continued possession of the monastery’s land’ (pp.46 and 44).

The first and longest of the Old English lives is found in London, British Library MS Cotton Caligula A.XIV, fols.121v-124v. The two other Old English fragments survive in London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427, fols.210r-v and 211r-v. The relationship of these fragments to that found in the Cotton manuscript and to each other is debated, but it seems feasible to me that the two Lambeth fragments are part of the same text, and that they are related only more distantly to the Cotton life. The provenance of the fragments is also open to interpretation but a Canterbury origin has been posited for the Cotton fragment, and Minster-in-Sheppey for the Lambeth Palace folios.

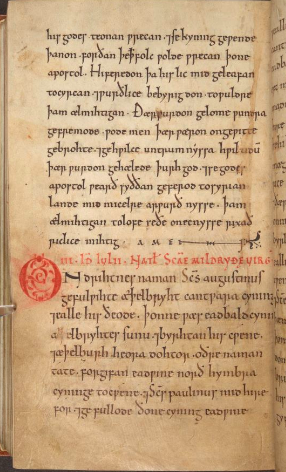

London, British Library, Cotton Caligula A.XIV, fol. 121v. © The British Library. Not to be reproduced by other parties without written permission from the copyright holder.

There is nothing in the manuscript context of the three fragments to suggest a close connection to early medieval women’s literary culture. Cotton Caligula A.XIV is a composite manuscript, and the British Library restricts access to it, not because it includes a life of Mildrith, but because it contains in fols.1r-36v the ‘Caligula Troper’, a fragmentary eleventh-century liturgical chant book (arguably produced in Winchester or Worcester) distinguished by its musical notation and very striking illuminations. In the thirteenth century, when the incomplete Caligula Troper was bound with a late twelfth-century Troper-Proser (fols.37r-92v), which is also potentially from Worcester, it was apparently still in use, judging from the annotations. The seven leaves of the fragmentary life of Mildrith are found near the end of Cotton Caligula A.XIV, where they appear, quite literally, in the midst of two other mid eleventh-century copies of earlier hagiographical works written in what seems to be the same hand: Ælfric’s life of St Martin of Tours, also incomplete (fols.93r-111v and 125r-130v), and his life of St Thomas the Apostle (fols.111v-121v). Why the lives of Mildrith and St Thomas interrupt that of Martin of Tours is unclear. It may be that the scribe was unable to locate some of the material he had relating to Martin of Tours so continued his work without it, and when he found it he simply picked up where he left off.

The fragments in Lambeth Palace, MS 427 also date to the eleventh century, and they are also misplaced, if for different reasons. They appear at the end of the composite manuscript, after the so-called Lambeth Psalter, which is renowned for its interlinear Old English glosses. The manuscript is of a South West English provenance, possibly from Winchester. The psalter is found in fols.5r-183v. There are also some other additions to the manuscript, including lines of alliterative verse (occupying the lower half of fol.183v). The psalter is followed by the canticles (fols.184r-202v), a litany of saints (fols. 202v-205v), some blank leaves (fols. 206r-209r), and some antiphons and lines of writing practice (fol.209v).

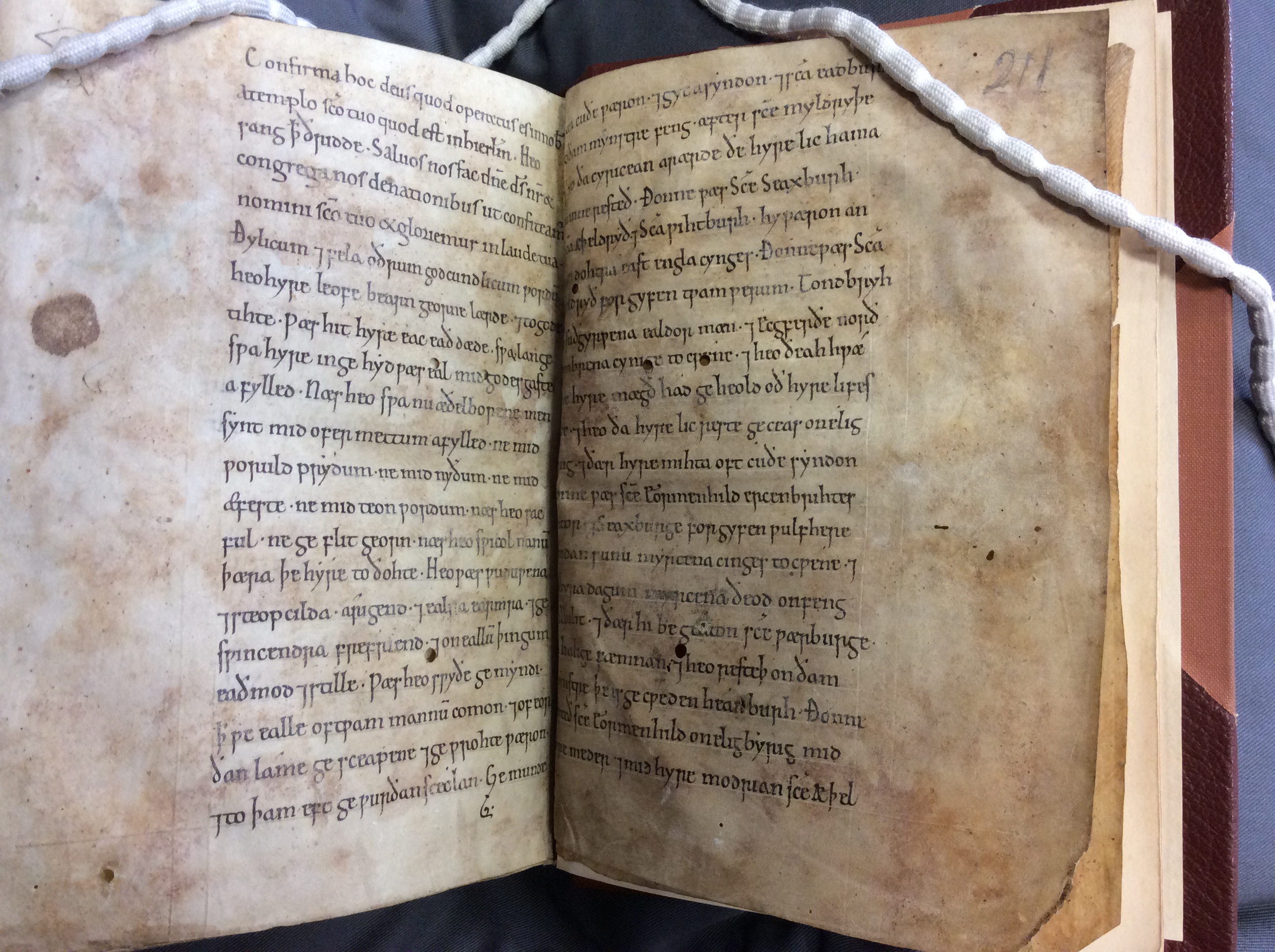

London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427, fols.210v-211r. Reproduced with the kind permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

The fragments, although of a similar date to the psalter, are added in a new hand, and are visually quite distinct from the folios that precede them: the parchment is slightly darker in colour and the leaves are fractionally smaller. As Elaine Treharne notes in her description of the manuscript (compiled with the assistance of Hollie Morgan and Sanne van der Schee), the fragments were actually used as binding leaves for the main manuscript contents sometime in the later medieval period (fols.1r-209v). There are stubs of two missing folios after fol.211. The precariousness of the survival of these fragments is therefore particularly marked.

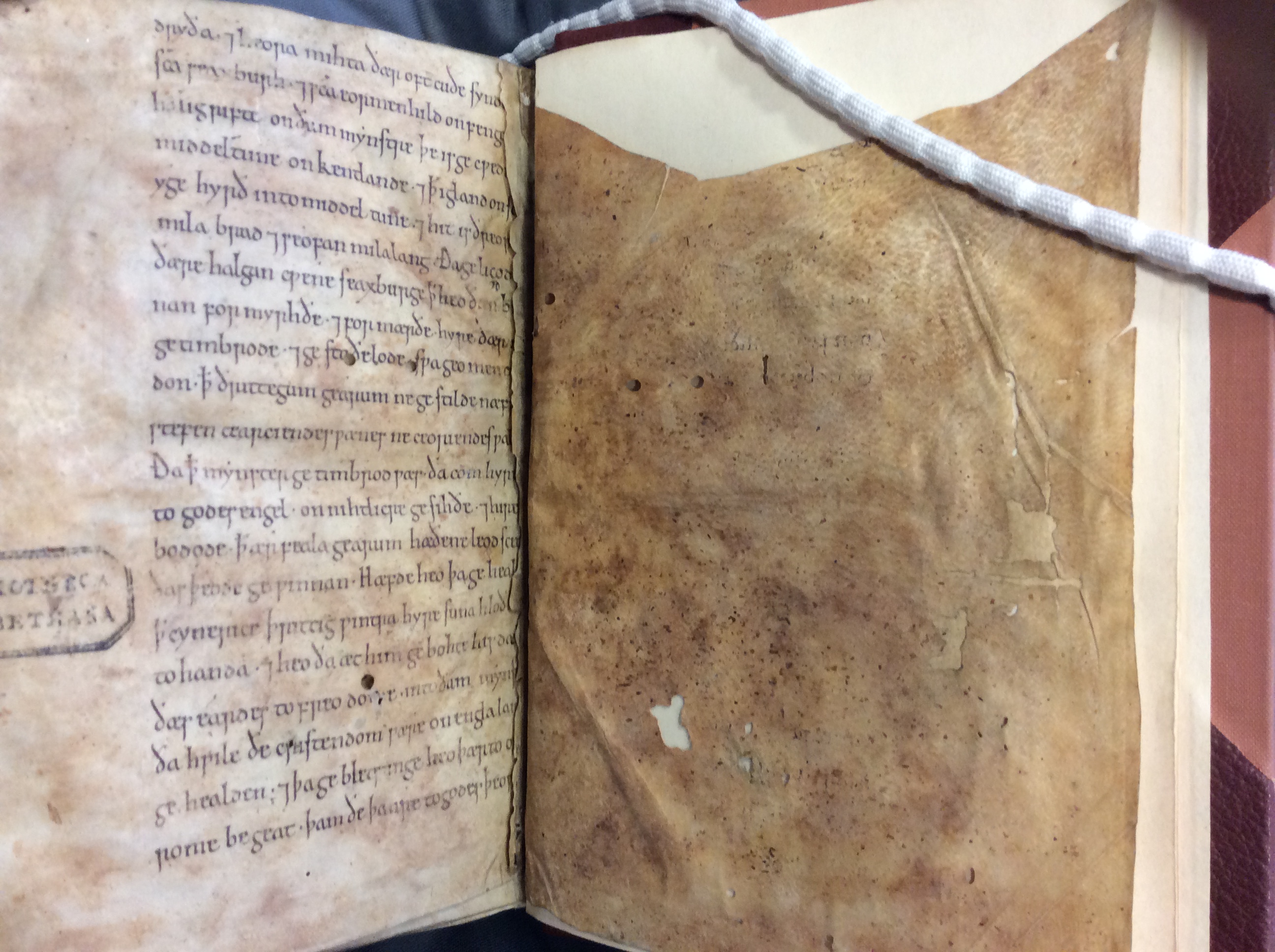

London, Lambeth Palace, MS 427, fols.211v-212r. Note the stubs of missing folios. Fol. 212 was at one stage a pastedown. Reproduced with the kind permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

The main evidence that connects the fragments with earlier female authorship is internal: all three address topics of relevance to women, and nuns more specifically, from the perspective of women. The Cotton version, for example, opens with a a genealogy and then provides an account of the miraculous foundation of the monastery at Thanet by St Mildrith’s mother, referred to here as ‘Domne Eafe’ [Lady Eve]. In fact it actually breaks off before Mildrith’s own life is recounted. For a succinct introduction to the story, which quotes extensively from the original, see this post by the blogger known as A Clerk of Oxford. The narrative, which establishes the abbey’s claim to the land of which it is built, is characterized by its use of the supernatural and Celtic folk-tale elements. The first of the Lambeth Palace fragments is rather allusive in its points of reference. According to Hollis, it appears, remarkably and uniquely, to describe the admission or consecration of Mildrith by her mother, Domne Eafe, but as Mary Dockray-Miller has noted, in a reading that pays greater attention to the indeterminacy of the fragment form, it could refer to any mother offering her daughter as an oblate (p.40). The second of the Lambeth Palace manuscripts is a royal and saintly genealogy that includes an account of Seaxburh’s founding of Minster-in-Sheppey.

Common to all three fragments is a focus on female empowerment, whether that be manifested in the active roles played by women, in the concern with what Dockray-Miller has termed ‘matrilineal genealogy’ (pp. 9-41), or in the attention paid to the rituals of monastic women. On the basis of their contents, all three fragments, then, can reasonably be understood as products of monastic women’s engagement with literary culture.

In connecting these three fragments and seeking out unifying themes, I have, to quote Arthur Bahr in his 2013 book on late medieval compilations, Fragments and Assemblages, sought to make them ‘speak with a voice that is intelligible, if not unified’ (p.4). Samantha Seal, in her recent review of Bahr’s book, observes that although ‘[o]ne cannot repair all the holes, nor create one single lasting narrative out of the fragments of text’, nevertheless ‘one can embrace the disruptive nature of that simultaneity inherent in partus, the breaking that is healed and broken and healed again ad infinitum.’

The same can be said of the history of early medieval women’s writing. As I have argued in my essay ‘Literature in Pieces: Female Sanctity and the Relics of Early Women’s Writing’, this history, like the manuscripts that are so integral to it, is ‘disrupted, discontinuous, fragmentary’ and so our responsibility as feminist literary critics has to be not to reject this, but to recognize the generative possibilities and to respond creatively and imaginatively (p.364).

We can do more than simply make the fragments speak: we can listen to the new stories that they tell.