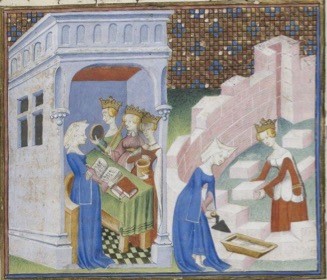

© The British Library Board: London, British Library, Harley MS 4431, fol. 3r – Christine presenting her book to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria

Is Christine de Pizan a member of the literary “canon”? Although she was recently cited as an example of a woman author who has managed to enter it, she certainly hasn’t always had a place there. So when did she enter the canon, and how? It would be more accurate to say that Christine underwent a kind of ‘double dip’ canonisation, by which I mean that after initially entering the canon, she was left out of it for a while, only going on to regain her place within it in the twentieth century. This blog post briefly traces these trajectories, showing that Christine’s is an example of an author whose place within the literary canon is far from stable.

Christine de Pizan was an active writer for thirty years (from around 1399 to 1429), and is believed to be the first professional woman of letters in French literary history. In her writings, Christine had a keen interest in promoting women’s access to education, and demanded that they be treated properly; it’s this interest in women’s issues that has led to her being labelled a protofeminist writer. She was present at the court of Charles VI of France, and used her time there fruitfully, writing texts that promoted these (along with many other) ideas for the French nobility, to whom she also presented copies of her works in beautiful illuminated manuscripts. Her recipients included the King’s uncle, brothers, sister-in-law, nephews, cousin, not forgetting King Charles VI himself, and his Queen, Isabeau of Bavaria. Her contemporary audience was, in other words, extremely limited. Although Christine produced at least fifty-four manuscripts during her lifetime, these stayed in royal libraries, were owned by noble patrons, and circulated amongst a very restricted group. Outside the royal sphere, Christine cannot have been a well-known figure. If she was a canonical author, it was only within the confines of this very small circle.

Paris BnF fr. 836, fol 1r – Christine presents her work to the King of France

In the century following her death, she did become more widely known. Her death in around 1430 was shortly followed by the invention of printing, which bolstered the circulation of texts whose readership had previously been fairly limited, thanks to which, Christine’s works reached international audiences through English, Flemish, and Portuguese translations. In terms of her reputation, she was commemorated and praised by her contemporary, the poet Eustache Deschamps, and by the next generation of great French poets, including Martin le Franc and Clément Marot. This period, I would argue, represents Christine’s first “dip” into the literary canon.

But the fifteenth century was a time of contradictions in terms of Christine’s literary renown: although her works were reaching new audiences, her name was simultaneously being erased from some of them. Copies of her works often circulated either anonymously, or were sometimes attributed to male writers. Her Livre des fais d’armes et de chevalerie was attributed to the fourth century Roman writer, Vegetius and a translation of her Proverbes moraulx circulated as though written ‘of […] Geffray Chaucers doyng’. Whilst her works had made their way into the contemporary canon, Christine herself was gradually being forgotten. Although earlier in the fifteenth century, Christine had a firm place within the French literary canon, like many medieval authors, she was relatively unknown within a century of her death. From the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, according to Earl Jeffrey Richards, references to Christine tend to appear in ‘discussions of royal historiography, of female erudition, of […] literary history […] or of fanciful, romanicizing author biographies’. In other words, she is only mentioned in the works of specialists. Christine’s name was known only to a few, and her works themselves were far from admired or even read. At this time, she can no longer be considered as a canonical author.

Fast-forwarding to the nineteenth century, and to Gustave Lanson’s Histoire de la littérature française of 1894, the book that is often regarded as having first established the French literary canon. This volume proceeds century by century, enumerating all the great works that its author deemed ‘unmissable’, but in the section on the fifteenth century, Lanson notably chose not to include Christine. He defends this decision as follows:

We will not stop to consider the excellent Christine de Pisan, a good girl, good wife, good mother, and moreover a veritable bluestocking, the first of that insufferable lineage of women authors, […] who […] have no concern but to multiply the proof of their tireless facility, equal to their universal mediocrity.

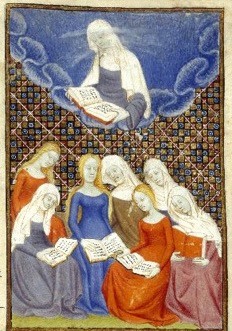

Although this pronouncement could have signalled Christine’s eternal banishment from the literary canon, the reverse actually took place half a century later, when her works were rediscovered by feminist critics. They were valued not only for showing a woman writer at work, but also for their testimony to women’s literacy, political engagement, and to a pro-feminist discourse that stood up against the torrent of misogynist texts that were rife in the Middle Ages. Christine’s manuscripts are also held in high regard for their visual programmes which literally show women in positions of power, including as rulers, as female knights, groups of women holding scholarly debates, a woman directing men in a scriptorium, female construction workers, and images of women, including Christine herself, teaching men.

© The British Library Board: London, British Library, Harley MS 4431, fol. 107r – Women Reading together in the Epistre Othea

But if, with the rise of feminism and of feminist literary criticism, Christine has enjoyed being reloaded into the canon, the terms of her presence within it are not the same, as the texts most enjoyed nowadays are not the ones that were most popular in the late medieval or early modern period. In the Middle Ages, by far her most popular text was a didactic treatise, the Epistre Othea, a poem with two prose glosses in which the goddess Othea teaches lessons based on the Trojan myths. But this unusual combination of poetry and prose in a non-narrative text doesn’t have the same appeal for twentieth and twenty-first century audiences. Instead, the current favourite is the Livre de la cité des dames, a much more overtly feminist text with a dramatic opening scene that has been adapted for radio and referenced in Amanda Foreman’s The Ascent of Woman.

Paris BnF fr. 1178, fol.3r – Opening Scene of the Livre de la Cité des Dames

Christine’s example shows that the literary canon is by no means fixed, and authors and works can dip in and out of it and, indeed, back in again. Her case also illustrates the separation that exists between the canonicity of a historical author and of their literary corpus: an author can be known to specialists without their work actually being read, and conversely, a work can circulate and be well-known without this being the case for the author, especially if that text circulates anonymously.

The idea of a shifting canon might make us a little uneasy, and I can’t help but wonder whether Christine’s place in it will be secure in the future. Ultimately, her unique position as a medieval woman writer, who wrote about being a medieval woman writer, should secure her name for future generations, but whether this means that her works maintain their place within the literary canon remains to be seen.

Charlotte E. Cooper, St Edmund Hall, Oxford

Earl Jeffrey Richards, ‘The Medieval “femme auteur” as a Provocation to Literary History: Eighteenth-Century Readers of Christine de Pizan’, in The Reception of Christine de Pizan from the Fifteenth through the Nineteenth Centuries: Visitors to the City, ed. Glenda K. McLeod (Lewiston and Lampeter: Mellen, 1991), 101-126