The second workshop in the Leverhulme-funded international networks research project, “Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon,” met at Boston University this summer from July 26th to 28th for three full and exciting days of papers, discussion and planning for future research. Entitled “Gender and Genre,” the workshop was attended by ten member of the Network team, who were joined by two scholars based in the United States and one undergraduate researcher, and two scholars based in the UK. Our larger project is an investigation of the substantial corpus of medieval English writing by and for women which sets out to show connections between women’s texts, genres and themes and those at large in medieval literary culture more generally. How does the consideration of women’s engagement with literature change our understanding of the established canon? Do Chaucer and other male authors have more in common with women’s literary culture than has previously been assumed? Participants in the project think these are questions that need asking and we asked them again in the beautiful and (in the Boston heatwave) mercifully cool seminar room at the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies.

DAY ONE

Diane Watt (University of Surrey), our Network leader, opened the proceedings by welcoming the group and paying tribute to the founder of the Center for Jewish Studies at BU, Elie Wiesel, writer, Holocaust survivor, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for 1986, who died only two weeks before the conference was to begin at the age of 88. After that, the workshop proper began with a paper by local network visitor, Nicholas Watson (Harvard University) on the “lost first draft” of the Book of Margery Kempe. Although it is often described as an autobiography, the Book is written in the third person, as though by a male cleric, and there have been several attempts to identify this clerical voice with that of Kempe’s second scribe, her confessor and parish priest Robert Spryngolde. Nicholas argued that Kempe was herself the creator of this voice, and wrote her own Book in the male genre of the woman’s visionary biography.

Difficulties of genre and situating medieval women’s voices continued to be at issue in the presentation that followed: Diane Watt, focused on the writing by Anglo-Saxon women in the collection now known as the Boniface correspondence. Can we approach these letters as expressing a specifically female experience of isolation and exile during this 8th century conversion mission, Diane asked? Suggesting these letters constitute “fragments of an early queer archive of migratory feelings” Diane further explored the way these voices collapse distance and have designs on us, as contemporary medievalists.

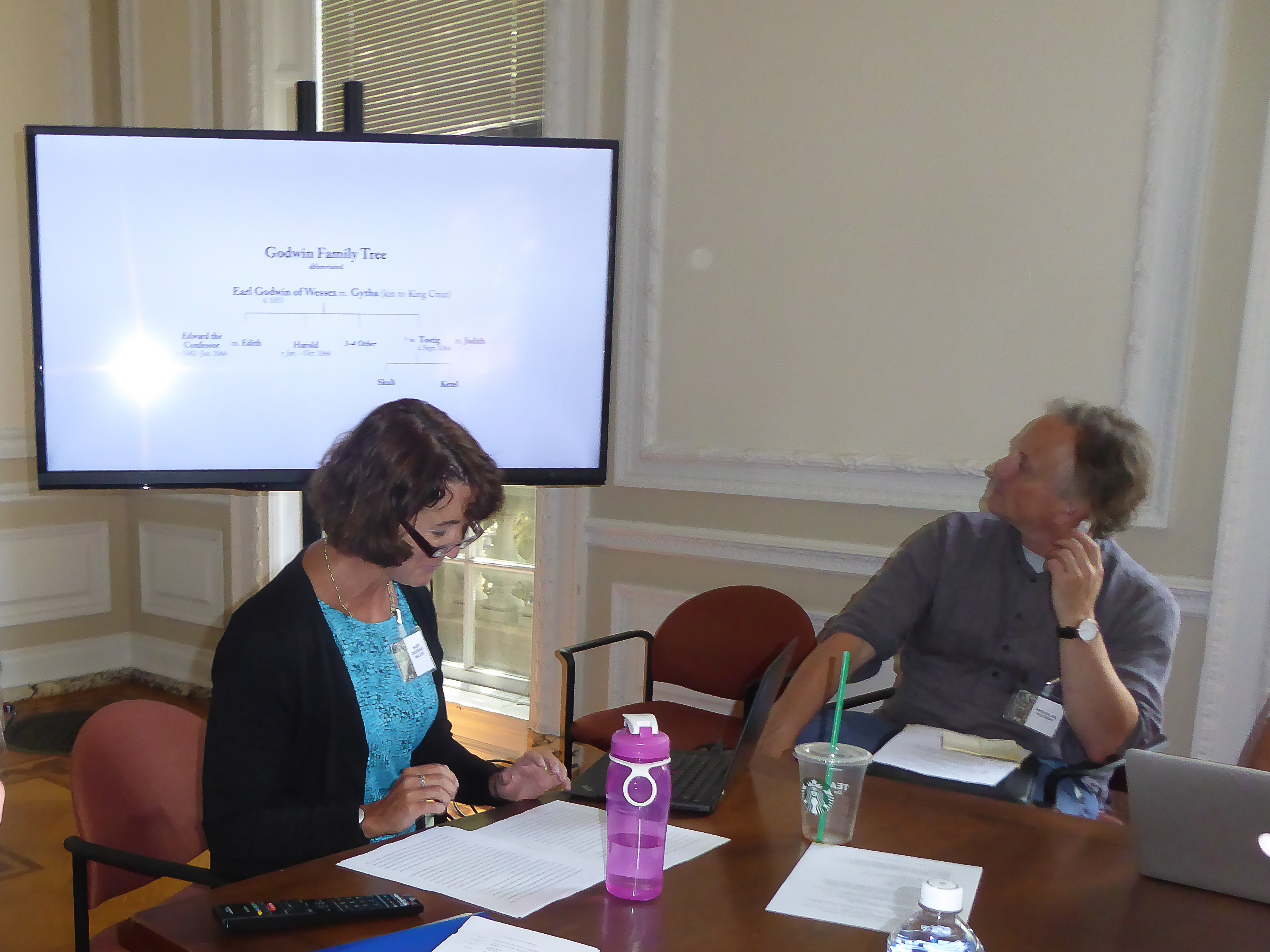

One of the particularly exciting aspects of this summer’s meeting was that we had the opportunity to learn about on-going research at other large, multi-year research projects with shared interests in women’s writing. Network visitor Mary Dockray-Miller (Lesley University) gave us an update on her current research that uses Lexomics, a digital lexical and textual analysis system developed at Wheaton College by Michael Drout http://wheatoncollege.edu/lexomics/, to ascertain the authorship of the Vita Edwardi. Mary argued that monk-hagiographer Goscelin wrote the text, perhaps for the retired Queen Edith while at Wilton Abbey during the mid-1060s. Following Mary’s paper, undergraduate researcher Jillian Valerio (Wheaton College) provided a demo of Lexomics and left us all excited about the possibilities this digital tool has for our own research needs.

After a lively discussion over lunch, Liz McAvoy (Swansea University) explored the echoes of Booke of Gostely Grace by visionary writer, Mechtild of Hackeborn (d. 1298) in late medieval literature, and especially in Dante’s Divine Comedy and the anonymous Middle English Pearl. With notable shared images, turns of phrase, and theological concepts, Liz argued that the Pearl-poet was familiar with both Mechtild and Dante, suggesting not only that Pearl needs to be read as informed by a well-established tradition of female spirituality, but also that our current assumptions about the poem’s early readership and authorship may need reconsideration.

Our last presentation of the day by Corinne Saunders (University of Durham) provided a glimpse into the work being done at Durham’s Wellcome Trust-funded interdisciplinary research project ‘Hearing the Voice’, which explores the phenomenon of hearing voices without external stimuli. Demonstrating that the project offers a valuable lens through which to view the Book of Margery Kempe, Corinne returned us to the problem of discernment of Margery’s own voice, this time focusing on the multi-sensory aspects of her visionary experiences, and how the Book consistently brings to the reader’s attention back to the problematic experience of (inner and outer) voices throughout the book, and the difficulty of articulating to others inner sensorial phenomenon.

DAY TWO

I began our second day, with a paper on Syon brethren Richard Whitford’s works that returned us to discussion of male writers’ drawing on traditions of female spirituality. In a 1537 compilation, Whitford’s A Work for Householders is joined with a death manual, A Daily Exercise of Death, which presents itself as written “at the request” of Syon Abbess Elizabeth Gybbs The death text includes rarified exercises of willed self-annihilation especially associated in the period with woman visionaries. Circulating widely during England’s violent 1530s, these works together redirect advanced female modes of spirituality to lay male political subjects as material for potentially activist and resistant praxes.

Our discussion of the imaginative role medieval women played in the religious and political conflicts of the sixteenth century continued with a presentation by Nancy Bradley Warren (Texas A&M University), whose paper centered on the Catholic William Forrest’s History of Grisild the Second (1558). Written for Queen Mary, Forrest retells Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale with Henry VIII occupying the role of Walter and Katherine of Aragon occupying the role of Griselda, drawing on both Chaucer as auctoritas and Marian devotion to offer Mary Tudor a model of “medieval,” “cloistered” queenship.

After lunch, Sue Niebrzydowski (Bangor University) got us out of our seats and into groups to puzzle over an Anglo-Norman prayer for the protection of women in childbirth. Written in the first person voice of the mother-to-be and with a special focus on the Virgin Mary, the prayer is found in deluxe books of hours, one of which names the prayer as by Matilda Becket (d. c. 1141), mother of Thomas Becket (b. c. 1120). This apparently utilitarian prayer, we found after analysis and discussion, was both theologically and linguistically complex and provided a fascinating glimpse into female pregnancy culture and uses of personal prayer.

Our discussion of Marian devotion and its special relationship in the period to female voice continued: Christiania Whitehead (University of Warwick) took as her focus the three short Middle English hymns of the hermit saint, Godric of Finchale (d.1170), in Reginald of Durham’s late 12th century Latin vita. While often studied as possibly the earliest post-conquest vernacular religious lyrics, in their original context the hymns form part of an account of one of Godric’s visionary experiences in which the female voices of his dead sister, Burgwine, also a recluse, and of the Virgin Mary are central. Read in context, these hymns present female (especially Marian) voice as especially associated with emergent vernacular textual practices and new musical modes.

DAY THREE

Laura Saetveit Miles (University of Bergen) was joined via Skype by Barbara Zimbalist (University of Texas at El Paso) and together they returned us to the question of the influence of female spirituality on late medieval English culture more widely. They focused on texts first written for Syon women such as the Speculum Devotorum as well as on the vitae of thirteenth-century holy women found in Oxford, Bodleian Library Douce MS 114, with Laura discussing imaginative community-formation and behavior regulation and Barbara discussing holy women’s reported verbal and vernacular expression as shareable devotional expressions. Medieval devotional texts, they suggested, not only formed communities, but individual readers through offering themselves as a focus for “participative piety.”

Following this, we had our third joint presentation and “state of research” update from the FNRS-funded multi-year project spearheaded by Denis Renevey (University of Lausanne) on late-fourteenth and fifteenth-century devotional compilations. Denis was joined by Marleen Cré (University of Lausanne) to discuss how devotional compilations work to mediate reader access to source texts, which might include more canonical materials from biblical, patristic or contemporary religious writing. Late medieval compilations always address or imply female readership, either professional religious or lay, suggesting the importance of this form of “mediating” textual dissemination for this constituency. Presenting important new research on the organization, address and provenance of The Chastising of God’s Children, and Disce Mori, Denis and Marleen explored the significance of female readers (implied or real) and enclosed religious culture to the popularity of devotional compilations in later medieval England.

In his wrap up, David Fuller (University of Durham) asked us to return to the word ‘genre’ in the title of this year’s workshop and offered a wide-ranging tour of various theories of genre, from classical canonical articulations of genre by Aristotle, and notes on genre by 19th and 20th century thinkers, including Burke and Derrida: how does genre form readers’ “horizons of expectation”? How is genre “an invitation to form”? Most interestingly, David pointed out that, although in the workshop title, genre as such was rarely discussed, but lurked quietly behind various recurring questions: is Margery Kempe’s book a ‘treatise’? Is an Anglo-Saxon woman’s letter best translated as a poem? Is there a genre particularly associated with women’s literary culture or is one of the signs of it mixed or hybridity of form? The implication of literary form in women’s literary culture, we agreed, is a question worth more discussion at the next workshop meeting.

Workshop Take-Aways and Notes for Future Research

Although participants presented on a wide range of texts and topics, our discussions returned with some urgency to a fairly concrete set of questions and concerns:

1) The necessity for more archival study and work on authorship, the production, manuscript organization and circulation of texts, and for closer engagement with new research tools and interdisciplinary approaches. It is clear from the new knowledges presented over the three days that we can’t assume that we know what the archive of women’s literary culture is, that it is complete, or that we already have a complete toolkit for approaching it.

2) The difficulty of discerning female voice and new formulations for thinking about it. The cultural role and particular form of women’s voices was a recurrent thread. We discussed both Margery Kempe’s inner voices and her textual clerical voice; the voices of Anglo-Saxon women, and the queer connections they create with us as modern medievalists; the voice of Mary and how it calls forth (in the imagination or in reality) the voices of real women, in prayer or in hymns; and various reports of spoken utterances that become shareable vernacular devotion.

3) Women’s religiosity, visionary and devotional, implied, real or imagined, as a crucial and marked player in the wider context of later medieval English culture: whether as inspiration for a male author’s poetic practice and theological imagery; as imaginary focus for individual and communal self-shaping; or as a modality deployed in the religious and political controversies of Reform and Marian England.

We fully expect and are excited to return to these questions at Bergen in June 2017, a meeting we began to plan at the end of this workshop in a presentation headed by Diane Watt and Laura Miles, who will host the event.

Amy Appleford

Boston University