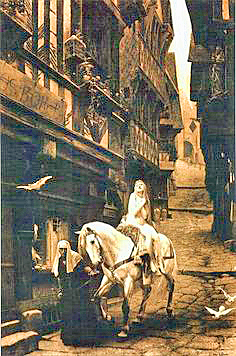

Image from Wikimedia Commons

How does a legend arise, and what purpose does it serve? Is myth the opposite of history, or can it elucidate the rather sparse hard facts that we inherit? And if the story of a noblewoman performing a highly unlikely action persists down through nearly a thousand years, what does that tell us of the period in which she lived and the hopes and beliefs of the intervening years. It was questions like these that aroused my interest in the Lady Godiva story, so universally known in Britain, and so variously interpreted and illustrated down the years.

Godiva is, without doubt, an historical figure. She was an Anglo-Saxon gentlewoman who lived between around 1040 and 1080 and was married to Leofric, Earl of Mercia. The correct form of her name, Godgifu, meaning ‘gift of God’, was fairly common in Anglo-Saxon England and is the name by which she would have been known before it was Latinised into the now familiar form of Godiva. We know that Godgifu was wealthy in her own right and that she was in all probability considerably younger than her husband. We also know that the couple were both generous benefactors, and that together they founded an abbey in Coventry.

When it comes to the famous ride, it is difficult to disentangle fact from fantasy. There are no contemporary records of it, the first mention of the story occurring in a document written by two monks in St Albans nearly a century after her death. They place the ride in 1057, and relate how Godgifu pleaded with her husband to relieve the people of their onerous taxes and how he, in a fit of pique at her persistent entreaties, agreed to do so if she would ride naked through the town square. In a spirit of generosity, she conceded to the deal and rode through the town on horseback, her body hidden by nothing more than her hair.

Other aspects of the story that appear in the various accounts include Godiva’s instruction to the townspeople to close their shutters and remain indoors so that no one should witness her shame, and the fact that Leofric did, indeed, revoke the taxes. A rather charming endorsement of this part of the story comes from Ranulf Higden (died 1364) in his Polychronicon, where he mentions the fact that Leofric freed the town from all tolls except those on horses. At the time of Edward I it was found that no tolls except those on horses were being paid in Coventry. Another later accretion to the story is the appearance of Peeping Tom, who disobeyed the instruction to refrain from observing Godiva’s nakedness and who was punished with blindness.

The level of Godiva’s sacrifice demonstrated by the story should not be underestimated. The name Godgifu means Gift of God, and a woman who performed such a self-sacrificial action for the sake of the people would most certainly have been seen as a gift from God. It is quite reasonable to suggest that in this story we have a respectable woman who makes what must have been for her the ultimate sacrifice for the good of her people. In other words, far from Godgifu being a salacious tale told for the titillation of men, it is actually a parable in which a woman is portrayed as an image of Christ.

In my sonnet, I celebrate this good and holy woman who, for the sake of the poor and downtrodden, performed a sacrificial act through which she was able to alleviate the misery of the people of Coventry.

Godgifu

She challenged the poverty and injustice of the age,

and when tears and arguments failed to hold much sway,

instead of reacting to bureaucracy with righteous rage,

she chose radical non-violent action to win the day.

The hair she’d brushed a hundred times each night

shone and shimmered, falling like a gown

to cover her nakedness and hide from curious sight

the beauty of her body as she rode through town.

To protect her modesty the people all agreed

to close their shutters and look the other way

until she’d passed, so that there’d be no need

to witness her sacrificial act that day –

except for a cheating boy who left this legacy behind:

for watching Godiva riding by, Peeping Tom went blind.