Figure 1: Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, Ms.65, f.141: A Map of Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

As part of my research into late medieval devotional practices and the performance of pilgrimage, I have primarily focused on the unique and idiosyncratic account of Margery Kempe’s travels to Rome and the Holy Land, as a means to better understand the role models that she follows, the broader textual community to which she belongs, and the local influences at work on her text. What follows is a brief insight into my broader research project, focusing here on the relationship between Kempe and St. Bridget of Sweden as a role model for sanctity and the performance of pilgrimage.

For Kempe, St. Bridget represents the gold standard of late-medieval sainthood to which she herself aspires to. The English mystic consciously structures her saintly-vocational-persona in Bridget’s image, as part of the argument that she puts forth for her own sanctity within her text, The Book of Margery Kempe. The importance of the Swedish saint for the lay mystic from East Anglia is stated both implicitly and explicitly throughout her work, in which Bridget’s text is mentioned by name several times, and has been noted by multiple scholars.

Figure 2: Casa di Santa Brigida, Piazza Farnese, Rome. Credit: Einat Klafter, February 2016

Kempe’s pilgrimage to Rome is not undertaken in the footsteps of St. Peter and Paul, but in those of Bridget, who called the Eternal City home from 1350 until her death in 1373. Rather than tour stational churches and other landmarks to amass indulgences for herself and her kin, Kempe deepens her knowledge of and connection to the Swedish saint, in a manner very reminiscent of the imitatio Christi tradition. She visits Bridget’s house (Casa di Santa Brigida), seeks out people who knew the saint and sites that were important to Bridget, such as Santa Maria Maggiore. For Kempe, Bridget is to Rome what Christ is to the Holy Land.

In doing so, Kempe offers something other than what we commonly find in the pilgrimage guides of the period, such as the Stacions of Rome, which Kempe would have been familiar with. She constructs a different spiritual experience for herself in Rome, an imitatio Birgittae, which remaps the sacred places and spaces of Rome, and creates a unique female-oriented pilgrimage circuit in Rome, which testifies to Kempe’s familiarity with the content of both the Liber Celestis and Bridget’s vita.

And yet, while Kempe’s account of her experience in Rome is Bridget-centric, the way in which she conceptualizes, articulates, and locates the sanctity of Rome breaks with the example that Bridget presents.

The Swedish saint, residing in Rome during the Avignon Papacy, is aware of and vocal about the poor material condition of Rome and particularly the state of the churches and relics, as well as the questionable moral compass of its inhabitants in the absence of the Pope.

Conversely, Kempe, visiting during the Great Western Schism, eschews the desperate material reality that she would have experienced in Rome and focuses on her encounters with the locals, primarily the poor, who are at the center of her mystical voyage through the city.

I believe this departure from Bridget’s texts is not the product of stylistic choices, or a reflection of vastly different material conditions in Rome, between the fourteenth and fifteenth century, which in fact would have been similar to those encountered by Bridget. Rather, it is a result of the different influences and pressures at work in the production of these texts.

Bridget, involved in papal politics and taking on an active role within the campaign to end the Avignon Papacy, emphasizes that the holy relics and churches of Rome are the wellspring of the city’s sanctity. Thus, she creates an un-transferable link between the sanctity of Rome and its soil – drenched in the blood of its martyrs – aiming to undercut the argument of ubi Papa, ibi Roma, used to justify the absenteeism of the Pope from Rome.

Kempe, unconcerned with papal politics, is instead focused on establishing her authority and status as a divinely chosen holy-lay woman, and is influenced by the anxieties over artifact veneration and pilgrimage practices raised as part of the English Lollard-fueled image debates, which were raging in her homeland during her time.

Unlike Bridget, Kempe is silent about the material conditions of Rome during her stay from August 1414 to Easter 1415.

This was a particularly tumultuous time of political instability and armed conflicts. The socio-political realities created by the Schism brought the Eternal City to the nadir of its fortunes. Particularly harsh was the last decade of the Schism, with bloody conflicts becoming a daily occurrence in Rome, because of feuds between rival Roman factions, along with reoccurring Neapolitan attempts to take, retake, and maintain control of the city. These included the sacking and burning of the city in 1413, and ongoing armed conflict around Castel Sant’Angelo during Kempe’s stay. Disease and famine were rampant in the streets of Rome, as described in great detail by St. Francesca Romana.

While Kempe is generally sparing in her description of places and spaces, she is neither oblivious to nor silent on matters that threaten her personal safety, be they natural or manmade. She frequently voices concern about the threat of being robbed or raped on the road, as well as more specific dangers, such as the political tensions that threaten to negatively impact her ability to freely travel to Danzig.

In addition, unlike Bridget and other pilgrimage accounts, Kempe’s text is also silent with regard to the great Indulgences and many relics that Rome had to offer, such as “the holy vernacle of Rome” referenced by Julian of Norwich from her cell in England.

Kempe’s account of Rome is instead densely populated with the people she encounters on the street of the Eternal City, and it is through these living beings that she connects with the divine in Rome. They do not simply replace the traditional artifacts through which the pious access the sanctity that Rome offers: they become devotional aids whose connection to the divine is so powerful that even the most fleeting encounter, such as the sighting of men walking in the street, offers Kempe the opportunity to access the spiritual benefits that Rome offers. She is gifted the intense experience of seeing Christ everywhere in the young boys and the “handsome men” she encounters, an experience so powerful and frequent that she must avert her gaze as she walks through the streets.

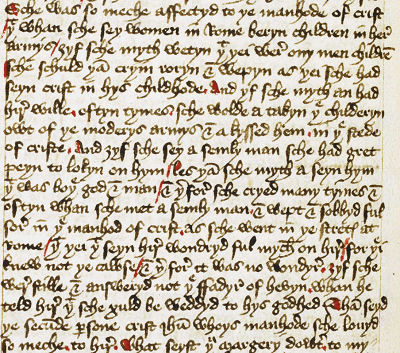

Figure 3: Add. MS 61823, f. 42v. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library

Such intense devotional experiences in Rome occur only in connection to the living beings through which she sees Christ and other divine personages. They enable Margery to access and connect with the sanctity of the city anywhere and in an unmediated way, without the need to seek out specific shrines or relics, which were accessible or displayed on set dates and times. Margery’s attention on people in Rome appears to reflect the call, circulated as part of the English image debates, that pilgrimage be made to people rather than artifacts. This is also found in other places in Kempe’s text, where the focus of her travels is on connecting with the friends of God “in divers placys of relygyon” – anchoresses, anchorites, priests, nuns, monks, etc. – rather than relics or artifacts.

Kempe does not access the sanctity of Rome only through the people she encounters, but also through the experience of poverty – her own voluntary poverty and the involuntary penury of others. The positive treatment of the poor in Rome is noteworthy, as this is the only instance in Kempe’s text where she mentions encountering the poor as an urban and everyday phenomenon. This raises the question of what makes the poor of Rome so special, since Margery did not need to step out of her native Bishop’s Lynn to find people in need, to embrace poverty, or to fully commit to the service and care of the poor.

This site-specific prominence of poverty is connected to Rome itself. In Kempe’s text, Rome enjoys special status over other sacred sites, due to its connection to Bridget, who lived a life of chaste poverty in Rome and begged for the poor outside of San Lorenzo in Panisperna.

Here we return to the importance of Bridget within Kempe’s text, in which poverty represents another connection to Bridget and part of Kempe’s performance of imitatio Birgittae in Rome. At the same time, it functions as a distinguishing characteristic of Rome as a sacred place, for it is in connection to her experience of poverty in Rome that Christ tells Kempe that “Thys place is holy.”

While scholarship has correctly identified the link between these two mystics and the near-dependency of Kempe’s narrative on the actions of her predecessor, it is also important to explore the differences between the two texts and the diverse external influences that may have shaped them. These differences can help us shed light on how local influences impact works that belong, or are seen as belonging, to a wider pan-European textual network and community. It is possible to identify the place of each text within this community and its connections to other works, while at the same time rediscovering and understanding the idiosyncrasies that make each of them unique.

Dr. Einat Klafter

Tel Aviv University

Twitter: @medievalk