Justin M. Byron-Davies and Ko Jeong-hee

In the early decades of Korea’s Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) a young woman who was renowned for her exceptional beauty, wit and keen intellect wrote the following reproof in verse to an eminent contemporary Neo-Confucian scholar:

‘What cause did I give you / To expect me to appear? / I never meant for you to believe / That I would disturb the fallen leaves at midnight. / Why blame me?/ It is the autumn wind that influences your delusion.’

The poet was Hwang Jin-i, widely regarded as one of the ‘Hermit Kingdom’s’ best-known female literary talents and viewed today as a proto-feminist figure, and Korea’s most famous Kisaeng.

Kisaeng were professional female entertainers and somewhat comparable to Japanese Geisha. The subject of Hwang Jin-i’s admittedly gentle rebuke was the eminent Neo-Confucian scholar Seo Kyong-duk, who would become her tutor and mentor. According to popular tradition, Hwang Jin-i wrote her sijo as a response to Seo Kyong-duk’s sijo in which he expresses his anguish at her nonappearance while awaiting her visit:

‘After my heart became unsettled / Every single thing distracted me. / In these shrouded mountains / What prospect of a visit? / The falling leaves in the autumn wind / Mimicked my lover’s approach.’

Seo Kyong-duk’s sijo contrasts markedly with Hwang Jin-i’s response. Whereas the scholar expresses his obsessive, all-consuming emotions which prompt him to view the natural world itself as heralding her imminent arrival, Hwang Jin-i, in her sijo, displays her characteristic logical outlook in language that is more cerebral than emotional and conveys brazen confidence borne of her self-awareness of possessing natural intelligence and physical beauty in addition to an array of talents which she cultivated.

This style is consistent with Hwang Jin-i’s other extant sijo. Thus, she subverts traditional male and female roles by stating that she had no intention of appearing before him, that it was the fallen leaves that prompted his futile anticipation, and that she is therefore not responsible for his delusion.

This introduces a previously unheard voice in Korean literary history: the voice of the woman who is loved more than she loves the counterpart.

Sijo are lyrical three-line verse which came to be written in the vernacular Korean script (Hangeul) interspersed with traditional Chinese characters (Hanja). Hangeul (Great Letters), King Sejong the Great’s revolutionary indigenous script created in 1443 (refined and distributed to the people in 1446), enabled the spread of literacy, whereas previously only the elite could read and write due to educational opportunities. The complex Chinese characters that were used prior to the development of the phonetic Hangeul script were impenetrable to the uneducated masses since as ‘borrowed’ script they bore no relation to spoken Korean. However, sijo were mostly disseminated through an oral tradition and were often sung; most were not written down until the eighteenth century.

From the forty or so extant contemporary stories from which we draw our limited knowledge of Hwang Jin-i, she is portrayed as a strong-willed, strikingly radical and highly sought-after woman who had relationships with several members of the Neo-Confucian literati who dominated politics during the Joseon Dynasty. Although she was a Kisaeng in Song-do (now Kaesong in modern North Korea) her fame had spread as far as the Neo-Confucian literati in the royal court in Hanyang (modern-day Seoul). Her main role was to entertain the local officials.

Unlike Seo Kyong-duk, who, according to a contemporary story about their relationship, rejected Hwang Jin-i’s initial attempts to seduce him, thus proving his virtue, other scholars were less respectable and she had no qualms about exposing their licentiousness and hypocrisy through the medium of satirical anecdotes, which found no shortage of keen disseminators and voracious readers and listeners who revelled in their subversive content.

Whilst the language of the sijo quoted above is deceptively simple, it is pregnant with allusions and hidden meaning, which require unpacking in order to capture their full resonance. It affords us an aperture into an analytical and perceptive mind. As with her other sijo, it draws evocatively on bucolic scenes as a backdrop to sexual politics. Hwang Jin-i’s gentle rebuke of Seo Kyong-duk belies the relatively precarious position of women in the hierarchical and staunchly patriarchal neo-Confucian Joseon society since far from being afforded the same opportunities as men, they faced restrictions on their movements and behaviour. A man was answerable to the king, a woman was answerable her husband, and after his death, she was to obey her eldest son. In contrast to male-authored sijo – which comprise most of the works within the genre – Kisaeng-authored sijo focus on personal themes of love and loss and can have the woman adopting the superior position to her lover.

Hwang Jin-i vocalises the woman’s predicament in a relationship whilst eschewing the normative focus on the male perspective. Far from demurely positioning herself as the one whose love is stronger she daringly reverses this commonplace so that it is the man who is vulnerable and susceptible to his emotions.

The Confucian prohibition of extramarital physical contact (for women) was frequently flouted and in practice Kisaeng were expected to seduce and provide sexual services if desired by, for instance, a bureaucrat who was posted to her province for a period of time. Indeed, non-compliance could result in corporal punishment or incarceration. She was expected to take the lead in initiating the relationship and subsequently become increasingly passive and deferential. Nevertheless, it was not unheard of for some Kisaeng to develop affection for the men whom they entertained. Yet such relationships were necessarily temporary since the bureaucrats could not take the Kisaeng with them when they were transferred, nor could they take a Kisaeng as a second wife due to strict rules designed to preserve the rigid class system (unlike these men, Kisaeng belonged to the lowest class of society).

Hwang Jin-i problematises this traditional gender role and in effect chastises the government officials whose disingenuous professions of love and false promises prior to their inevitable departure at the end of their posting.

Kisaeng, should not be confused with prostitutes; the rigorous and lengthy training which they had to undergo equipped them with literary competence and the ability to entertain the higher echelons of society, whether in the form of conversation, musical performances, or composition, and serve as companions to aristocratic Korean politicians (Yangban). Although during the late Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) some Kisaeng served at the royal court, from the mid Joseon Dynasty, they were not permitted to perform at the royal rituals. Nevertheless, some Kisaeng were permitted to attend royal banquets for the king’s pleasure. The abilities and opportunities of Kisaeng were anomalous in terms of societal practices, and women’s contribution to literature was restricted; notwithstanding the restrictions which applied to all women, kisaeng were able to give a voice to the contemporary marginalised woman through their greater autonomy.

This enabled Hwang Jin-i to express her emotions in ways that contrast with sijo written by male neo-Confucian poets, which is characterised by formality and clearly defined rules.

The most highly regarded Kisaeng had a degree of artistic licence to mock aristocratic men and speak truth to power through metaphors and similes, and Hwang Jin-i displays her wry sense of humour in her playfully reproving tone. Such specific freedom to criticise their lovers also provided them with qualified exemption from political threats. This was possible because of the kisaeng’s perceived harmlessness, attributable to their low status and the prejudice and complacent underestimation of their literary and intellectual capabilities.

Hwang Jin-i’s astute, uncompromising, dissenting, yet teasing and therefore disarming voice, provides a counterpoint to other works within this male-dominated canon.

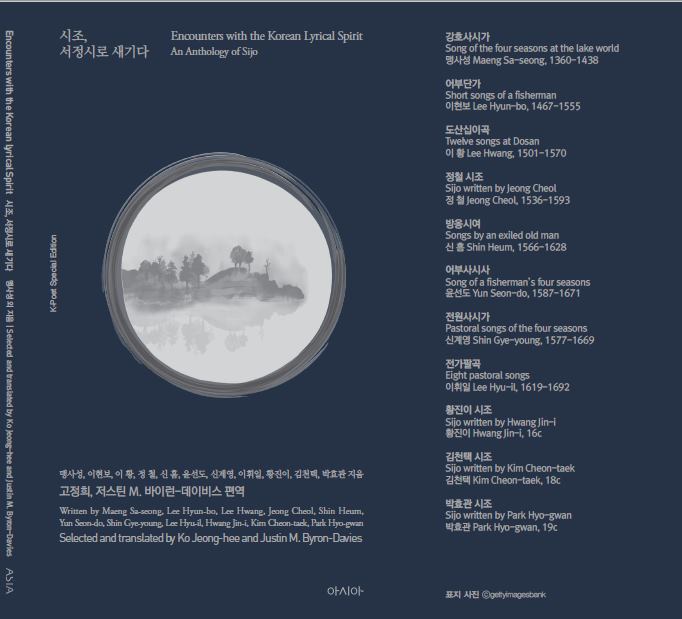

In order to gain a more comprehensive view of a given literary tradition it is important to give a platform to both male- and female-authored works. Therefore, we sought to make our translation of selected sijo, Encounters with the Korean Lyrical Spirit: An Anthology of Sijo (Seoul: Asia Publishers, 2019), as accessible as possible by making it a parallel text edition (Korean and English). Just as in medieval English literature the voices of women writers such as Julian of Norwich are regarded as, at the very least, the equal of their male contemporaries, it should come as no surprise that the writing of the marginalised voices of women elsewhere in the world, when heard, match those of their male counterparts.

Hwang Jin-i’s sijo complements the work of her male contemporaries even if she is not always complimentary of the male scholars and bureaucrats with whom she crossed paths.

To order Encounters with the Korean Lyrical Spirit from Amazon.com click on this link.

You can listen to a KBS World Radio interview with Justin M. Byron Davies in which he discusses the volume here.