At one level, the denunciation by UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, of the party’s 2010 General Election manifesto as ‘drivel‘ at the end of last week merely confirms the image of plain-speaking, see-as-they-find types, unafraid to change tack as they develop. Certainly, it’s almost impossible to imagine any other party leader (and not just in the UK) doing the same and living it down, especially if they too had written part of it and defended at the time.

However, it also exposes something about the nature of the party.

Manifestos have always been a sore point for UKIP, ever since it’s foundation in the early 1990s. Back then, the founding leader, Alan Sked, wanted to have just one policy – of refusing to take up seats in the European Parliament, so as to cause a constitutional crisis that would result in British exit from the European Union – and nothing else. since UKIP MEPs (and by later extension MPs) would do nothing except push for this outcome, there was no need to produce positions on anything else.

From such purist positions there has been much subsequent expansion, especially as the prospect of actually securing seats drew much nearer in the late 1990s with the switch to PR. In the absence of the immediate overthrow of the system, the party began to build its views on various matters. Most obviously, the increasing interest in immigration provided a clear opportunity to mark out some territory upon which other parties (committed to EU membership) could not completely close down.

However, it was only with the 2004 EP elections that a much more coherent manifesto emerged, largely as a function of the guidance of Bill Clinton’s former advisor Dick Morris. His suggestion that the party needed to be more aspirational in its marketing, building on a platform of ‘independence’ in the broadest sense, lent a structure and direction to the manifesto itself. This was not without reprecussions, though.

Most importantly, as UKIP’s profile (and that of eurosceptics more generally) has grown over the past decade, so too have the cries that there is no substance of ideology or policy to the party: the ‘no good alternative’ line of argument. This has stung, since it was evidently true and (ostensibly) easy to remedy: just sit down and write some policies.

As any party member can tell you, it’s not that easy. And it’s especially not easy in a party that lacks an ideology. UKIP often makes much of the fact that it draws from across the political spectrum, but the pay-off is that not much holds them together, except the negatives of disliking the EU, immigration and ‘the system’.

While those on the right have built up the idea of the Anglosphere as a counterpoint to European integration, UKIP pushed out production of its manifestos to small groups of activists who were interested in such things, largely so that come the 2010 election, the leadership could point to the substantial looking document and say “of course we have policies”. Even if they hadn’t obviously read them.

Farage’s description is thus fairly apt, in the circumstances, and in the context of having a shot at getting MPs into the next parliament, he was right to drop the text.

But this now leaves the party without a manifesto for the May elections, a position that is very much an oddity in modern politics. Especially when one considers that it is still likely to come first in voting.

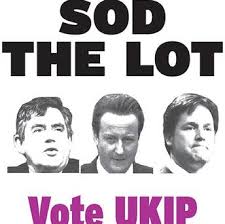

Part of UKIP’s success is the way in which individuals have made the party to be what they want: typically a rejection of politics as usual. The absence of a manifesto might – paradoxically – reinforce that impression, and so do more good than harm and the UKIP ‘brand’ is strong enough to weather the next four months like this.

The more interesting point will come after that, as it tries once more for Westminster. This is first-order politics and jovial bonhomie won’t get very far in debates about the economy, welfare or health.

However the party does in May – good or bad – it’ll still have the same difficulties it has always had in producing policy. It will be a busy summer and autumn for them, trying to decide what they put into that document, and it is a process that will bear very close scrutiny.