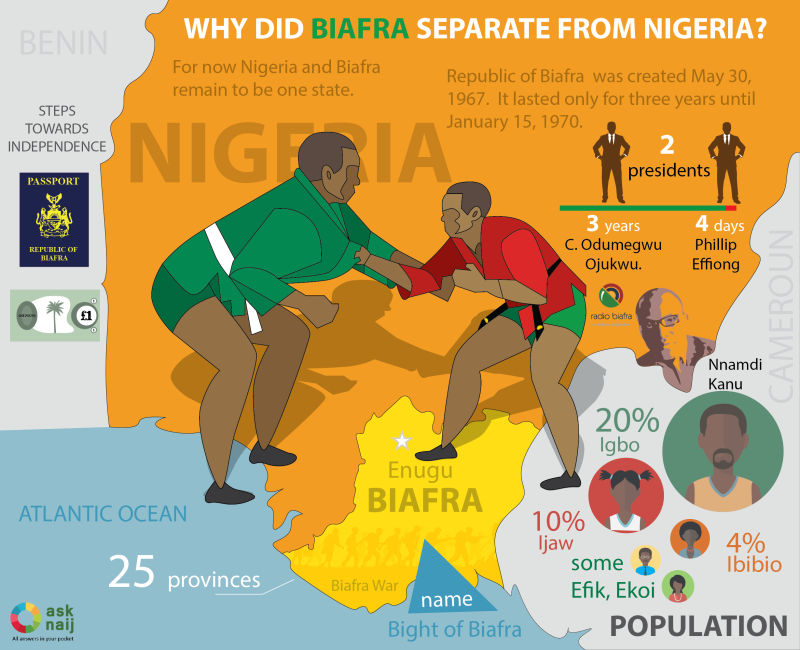

Nigeria, showing the former Eastern Region that on 30 May 1968 decared independence as the Republic of Biafra:

Speaking in 2015 about some of the worst horrors of the Second World War the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, said: “Remembering well is essential to forgiving completely.” This could have been a motto for the “Remembering Biafra” conference held earlier this month at George Washington University. It was an extraordinarily powerful event both emotionally and intellectually and it was a privilege to attend and to give a presentation, based on personal experience, on some of the humanitarian dilemmas of the Biafran war.

Although the war occurred 50 years ago it continues to arouse strong passions, not least because of the sheer scale of the man-made disaster it represents and the tragic loss of life, especially among children. It was also a catastrophic failure of international intervention to stop the suffering. All the more important, then, that we should have a clear understanding of the causes and the nature of the conflict and that we should “remember it well”. As the Nigerian author of the prize-winning novel[i] about the Biafran war Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose inspiring keynote lecture was the climax of the conference, put it: “It is almost a moral imperative – we have to remember.”

And yet the Biafran conflict is less visible than it should be. This is partly because when the war ended it was in a sense swept under the carpet. The then leader of Nigeria, General Gowon, declared a policy of “no victor, no vanquished”; at the time this was welcome, not least because part of the reason the war lasted for so long was a fear among the Ibos, who were the dominant people in Biafra – and who had suffered horrific massacres in other parts of the country prior to the conflict – that if they lost they would become victims of genocide. However, while people in Biafra had experienced terrible trauma during the 30 months of the war, life in the rest of Nigeria had continued more or less as normal; this meant that those Nigerians not from the East had no real comprehension of what their newly reunited compatriots had suffered and failed to understand how vital it was to recognise this. The war was over but it was not remembered well.

Instead, the former citizens of Biafra were allowed to convert only a paltry £20 of their Biafran currency savings into Nigerian money by the government, and many feel deliberately marginalised by successive federal governments even to this day. One of my fellow speakers commented “A lack of will to acknowledge that there is a wound means there can be no healing”. The impact on – and the role of – women in the conflict is especially under-acknowledged; as one speaker put it, the war had left an “indelible mark” on many of their lives. Another contributor commented how striking it was that there was no official commemoration of such a momentous and tragic event in Nigeria’s history; as Adichie put it, “Formal state actors have silenced both history and memory.” And another speaker recounted how Nigerian university students had recently been prevented by the authorities from holding a debate to understand better what had happened over Biafra. Clearly there is much unfinished business left over from the conflict.

The presenters included US-based Nigerian/Ibo academics, who described a generational difference in terms of how people relate to the war; as one of them put it “The older generation is at the vanguard of those who want to move on; the younger ones are at the vanguard of those who want to understand”. Adichie herself commented: “Had I experienced the war, I do not think I could have written Half of a Yellow Sun”. Our panels generated an extraordinary amount of pro-Biafra comment on social media. This has to be seen in the light of a resurgence of the Biafra movement in Nigeria and among the diaspora, which in turn has provoked a sometimes brutal response from the security authorities. Given the history of Nigeria since the end of the war one can see why the same lack of belief in the country that led to Biafra’s secession in 1967 is powerfully present among some young people today.

Remembering well therefore means acknowledging the trauma of the past, asking for forgiveness, and forgiving. But it is also about historical accuracy; if the story is not properly told the truth itself becomes a casualty. This is not helped when ‘alternative facts’ circulate on social media, for example the assertion that “3.5 million Biafrans were massacred”. Not only is the number wildly exaggerated – the estimate of total deaths in the conflict made at the time by the well-respected chronicler John De St Jorre[ii] was 600,000 (which is bad enough) – but the use of the word “massacre” in this context is itself misleading. There certainly were massacres, but the vast majority of deaths came not from the fighting but from starvation and disease among the civilian population, particularly the poorest and most disadvantaged members of Biafran society. And while the Nigerian economic blockade played a major part in this, so did the willingness of the Biafran leadership to use the suffering of its own people as a means of rallying international support to its cause.

One must also challenge the frequent use of the term “genocide” in the context of the conflict. Undoubtedly there were parts of the Nigerian state apparatus that had murderous intent towards the Ibos living in other parts of the country, and the killings that occurred in 1966 would in modern parlance certainly be seen as “ethnic cleansing” and “crimes against humanity”. During the war itself atrocities were committed by the Nigerian army and air force against unarmed Biafrans, including civilians; the lack of accountability for these war crimes is itself an outrage. However there never was any substantive reason to believe that a Nigerian military victory would be followed by genocide; abuses there were, but not systematic mass killings. This was a myth that sadly dominated the way ordinary people thought about the conflict, and it contributed to their suffering. Out of fear for their lives many of them fled into the bush rather than stay in their villages and face the advancing Nigerian army; when finally they were persuaded to emerge many of them were in a truly terrible state having had virtually nothing to eat for several months.

Admittedly there is room for debate about the meaning of “genocide” as expressed in the 1948 Genocide Convention. And one of the speakers pointed out that if you go to bed every night not knowing whether you will be alive in the morning the wording of international conventions is somewhat immaterial. As Adichie put it: “Objective evidence can sometimes be incomplete”. Nevertheless it would seem important to be able to distinguish between what happened in Biafra and, say, events 27 years later in Rwanda, where there was a deliberately orchestrated attempt to eliminate an entire ethnic group. We can and should acknowledge the absolute horror of what happened in Biafra without needing to stretch the meaning of a word. What matters is that the ordinary people of Biafra suffered a huge injustice for which there has been no reparation – and which their children cannot forget.

As Dean Brigety of the Elliott School of International Affairs said in opening the conference, “The subject of Biafra is still an extremely sensitive issue… nevertheless our duty as an academic institution is to be brave enough and respectful enough to examine controversial and challenging topics in an environment that leads to more understanding.” The conference certainly achieved that but it also revealed the scale of the task in taking that discussion to a wider audience, particularly in Nigeria. Over the years there has arguably been more informed analysis of the conflict outside the country than within it, and that needs to change. Despite a long-standing intellectual and emotional involvement with the subject of Biafra, I left the conference painfully aware of my limited ability as an outsider to judge it; that task now has to pass to those who have inherited its legacy. Like Adichie’s character Richard, the English writer who goes to Nigeria, stays, falls in love – with the place and the people – takes part in the struggle, and shares the traumas of life inside Biafra, I have to accept: “The war isn’t my story to tell, really.”

[i] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Half of a Yellow Sun (Fourth Estate, 2014 – originally published 2006 by Knopf Anchor).

[ii] John De St Jorre, The Brothers’ War, (London: Faber, 2009 – originally published in 1972 by Hodder and Stoughton as The Nigerian Civil War) p412.