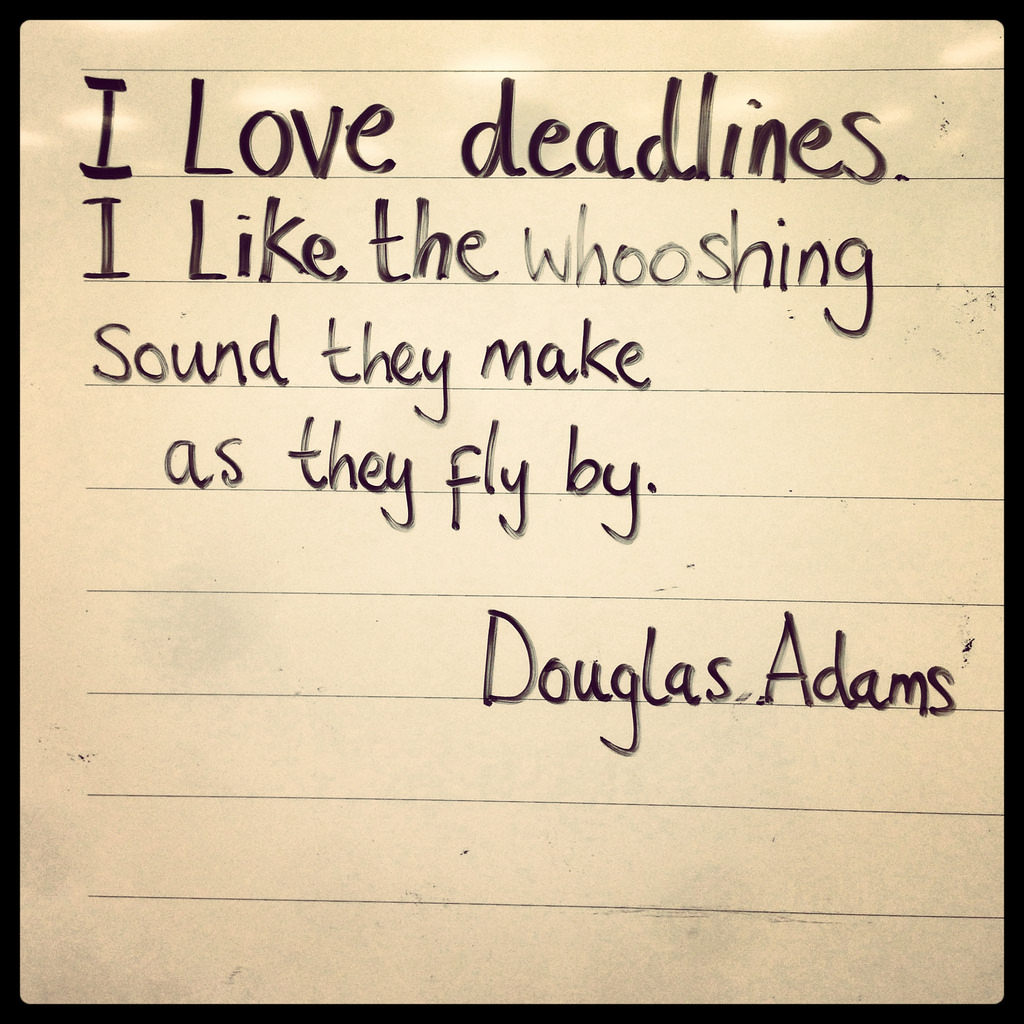

Sometimes one has the impression that everyone involved in European politics is a big fan of Douglas Adams: certainly, as far as Article 50 goes, each new day brings absurdity piled upon absurdity.

Sometimes one has the impression that everyone involved in European politics is a big fan of Douglas Adams: certainly, as far as Article 50 goes, each new day brings absurdity piled upon absurdity.

The last week has made this point better than most, with the sudden rush to agreement on Monday then brutally undercut and a new stasis emerging.

It’s easy to be very negative about it all – confirming as it seemingly does – everything you thought was wrong with everything.

But for once I’d prefer to stress the positives from the latest batch of events, in the spirit of goodwill to all.

The most obvious positive to take away from it all is the capacity of both sides to demonstrate flexibility and movement in their positions.

Prior to the start of last week, there had been little evidence for this. The British government had stuck to its vague pronouncements that didn’t cohere, while the EU seemed to be on a loop in restating its principles and red-lines.

The apparent clarification on finances helped to open this up: the UK committed more clearly to honouring the large bulk of current liabilities, including the RAL (which makes up most of these), which removed one of the biggest blocks in the road. More importantly, the finances was the most fungible of the Phase I issues and the most pressing for most of the EU27, so it set a positive tone for what might come next. The money was thus both important in itself and as a marker of intent, not to mention signalling that the UK might come round much more to the EU’s position than the other way around.

Even if citizens’ rights was still stuck on the role of the CJEU – something that will be coming back before long – the second key development was a consensus among the negotiators that a statement of intent on the Irish border would be enough to move this latter topic on to ‘sufficient progress’.

This matters because the underlying difficulties of resolving the border question remain as stark as ever. The incompatibility of the EU’s single market, the Good Friday Agreement, the common travel area, UK territorial integrity and UK withdrawal from the single market/customs union has no solution in purely formal terms. Even the UK’s vagueness about ‘technical solutions’ couldn’t really address this point, as Dublin had made repeatedly clear.

Importantly, Phase I is the point at which Ireland has the most leverage, especially since the rest of the EU appeared to stand squarely behind it: to let the UK get away with what it had offered previously would be to risk losing any chance to pin it down, as the agenda moved on.

The compromise then was to work on a statement of principles that would apply whatever the outcome – i.e. including a no-deal scenario – to keep the border open and the GFA operative. With some linguistic fancy footwork on ‘regulatory alignment‘, it was possible to carve out a bit of space whereby the EU could claim no regulatory gap – so removing on key arm for needing a hard border – and the UK could claim it had its own regulatory process – albeit one that one have to very closely follow EU rules.

Put differently, the EU moved on form – from a detailed plan to a detailed set of principles – while the UK moved on substance – effectively tying themselves into the EU’s preferences and regulation.

This compromise seemed to work well enough for all the principals to sign off on it, right up to the point that the DUP raised their objections. But this shouldn’t obscure that the movement took place at all. It now sets the agenda for the work going on right now.

And this is the second big positive to take away: everyone’s working very hard for a deal.

Of all the counter-productive language since last June, ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’ has been the most problematic (and the one producing the firmest response from experts).

Every since Monday afternoon, when the wheels came off the compromise deal, figures on all sides have been very keen to stress the positives. The May-Juncker press conference was very brief, but couched entirely in such language, while briefings on all sides kept to the script too. While it would have been tempting to stick the boot into the DUP, the Irish government has made repeated positive noises about the chances of salvaging a new text this week or next, and appears determined not to rock the boot for May.

Just as important has been the language in the UK. With Davis distracted by the impact assessments this week – which also says something about the British situation – it was May taking the lead and again pushing the line that agreement was still possible. While it might be understandable, given her position, it was also apparent that most of her party wasn’t trailing the ‘no deal’ line and that Labour was challenging her competence, rather than the substance of what she had negotiated.

Most importantly in all of this is the Douglas Adams point about deadlines. Yesterday had been set by the EU as the last date to get text agreed in time for the EU27 to discuss prior to next week’s European Council. That has now drifted out to at least tomorrow and possibly early next week. Moreover, Leo Varadkar’s statements also open up the possibility of a special European Council early in the new year, should things not pan out, so that Phase II doesn’t have to wait until February.

Taken together, the impression is that Article 50 is still a going concern and that all sides are serious about making it happen. Certainly, the UK still has tremendous problems with its internal politics, but the fact that it could move as it did should give cause for some positivity about it all.

But a final word of caution. This past week also suggests that the outcome of Article 50 is now likely to be only one of two outcomes: either a deal very largely on EU terms, or a complete lack of agreement. The middle path of a more tailored deal looks less and less probably now. That might sound good to some, but the polarisation of outcomes also raises dangers, especially as and when Phase II opens.