All that summer rest finally gave me the impetus to put together this little chart the other day.

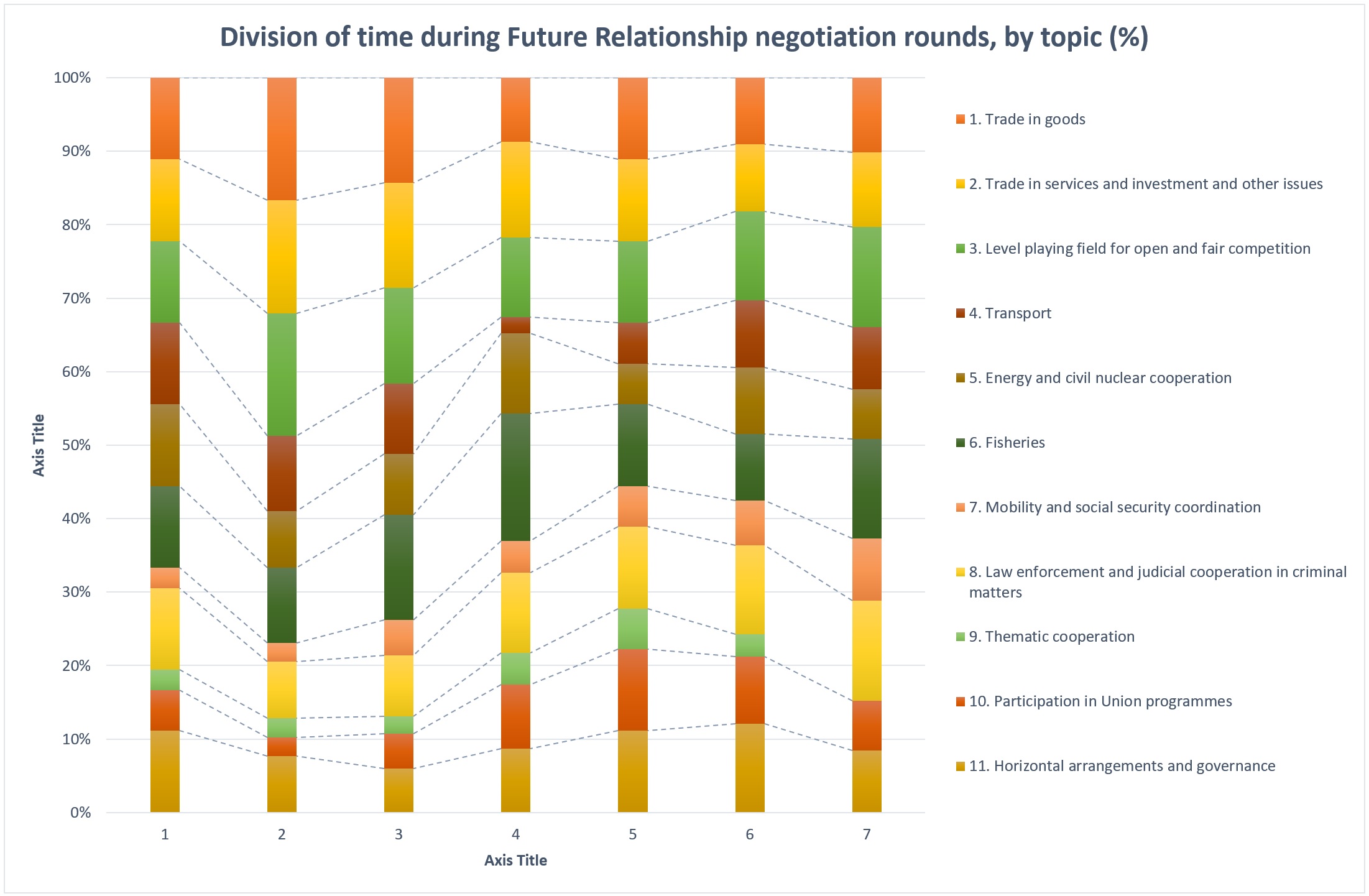

It’s a simple breakdown of the time allocated to the 11 headings of the Future Relationship negotiating rounds, including this week’s 7th. Weightings are based on a negotiating block (usually a half-day), with some joint sessions (e.g. governance and aviation) being split evenly between the two original headings. All the data is based on the published agendas.

When I posted on Twitter, I focused mainly on the stability of the time allocations, reflecting the non-agreement on any one chapter: the entire agenda is still in a state of nascent points of common ground, but awaiting now the political level to push into any horse-trading that might occur. Without that push, we’re not going to see things change, or indeed resolve into agreement, regardless of what rational cost-benefit analysis might tell us should happen.

Others have written on the politics of the calculations involved, so I’m not going to add further to that pile, but instead I’ll pick up on the comments I got about the time devoted to fisheries.

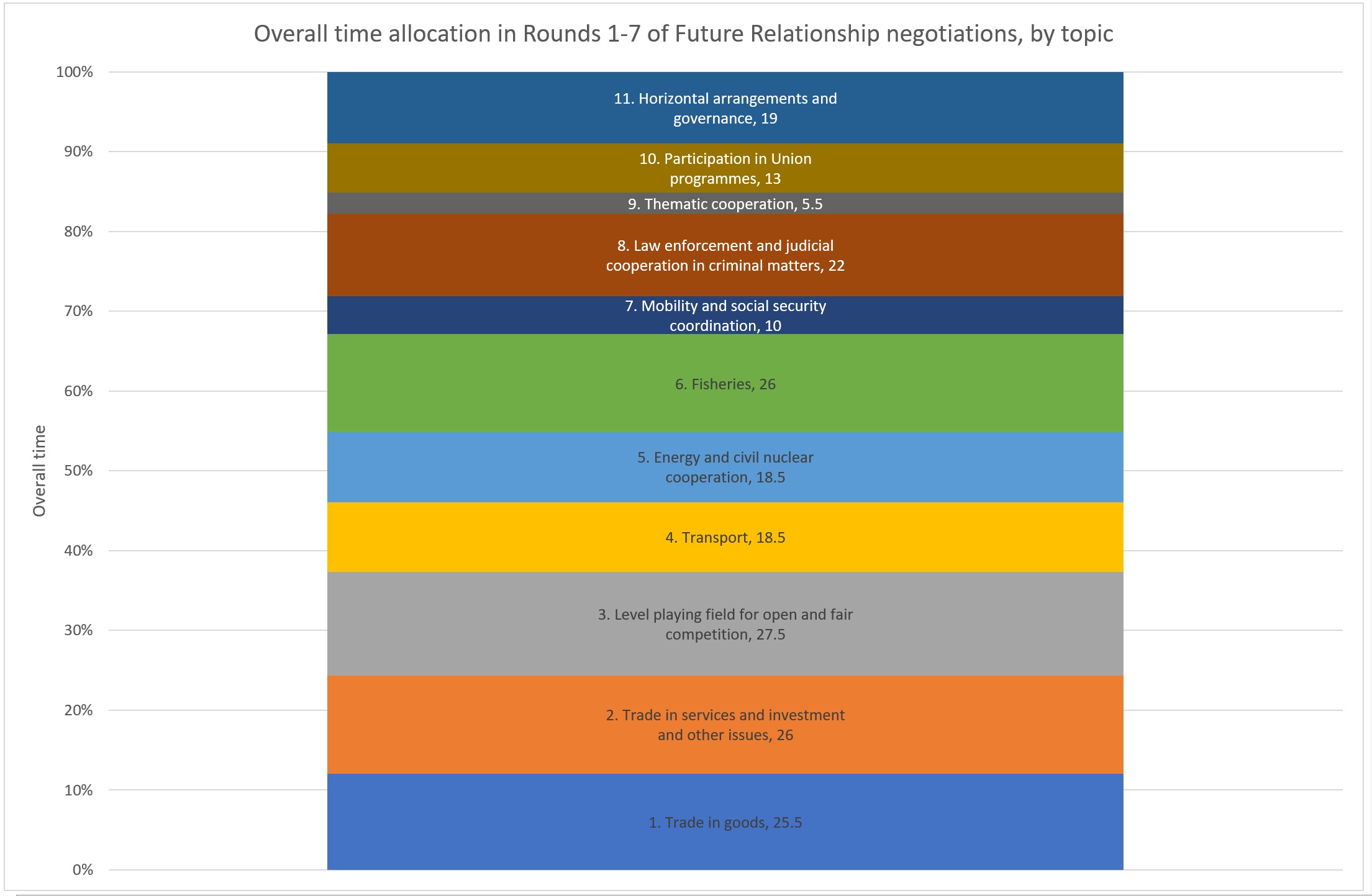

People rightly pointed out that fisheries contributes a trivial amount to economic activity, certainly compared to services, and yet it gets just as much time (only the Level Playing Field gets more).

A quick glance at that overall distribution of time will show that economic value is not the driver here.

Instead, it’s about the production of legal text to meet the needs of the parties involved, as well as the degree of disagreement between them.

Time in negotiations is shaped much more by the logic of the agreement than by objective external benchmarks: the process of negotiation itself becomes part of what is discussed.

In some cases, the parties might have minimal disagreement, so it’s relatively quick and simple to close the gap. In others, there might be big differences, but the nature of the field might only allow for one position or the other, so the only discussion is about whether either side concedes the point, or rather that it falls.

The difficult and time-consuming cases come when there are multiple options available – including novel ones – or where there are additional legal obligations to be factored in. Fisheries is a good example of such a situation, given assorted bits of international public law, fishing conventions, environmental protection obligations and more ways of managing things than you’d think would exist.

Services, by contrast, remains an underdeveloped area of international cooperation, so a lot of what’s going on is about degrees of alignment to EU rules, including on financial equivalence. In addition, the UK isn’t asking for nearly so much on this front, as compared to fisheries.

In both cases, the time taken to produce legal texts for inclusion in a new treaty takes time (and you can read the Withdrawal Agreement‘s many annexes for a relevant illustration of how politically not-so-important points can take up a lot of legal space), but it’s not as simple as saying that works on the same basis as the politics of the situation.