The conclusion of the EU-UK Trade & Cooperation Agreement (TCA) over Christmas meant that the end of the transition period a few days later saw the start of a new phase of the relationship between the two parties.

Since there are many others who are much better placed to analyse the contents of the TCA (e.g. Steve Peers, Chris Grey, and the entire UK in a Changing Europe massive), I will limit myself here to discussion of just one aspect, namely the structuring of future EU-UK relations within the treaties.

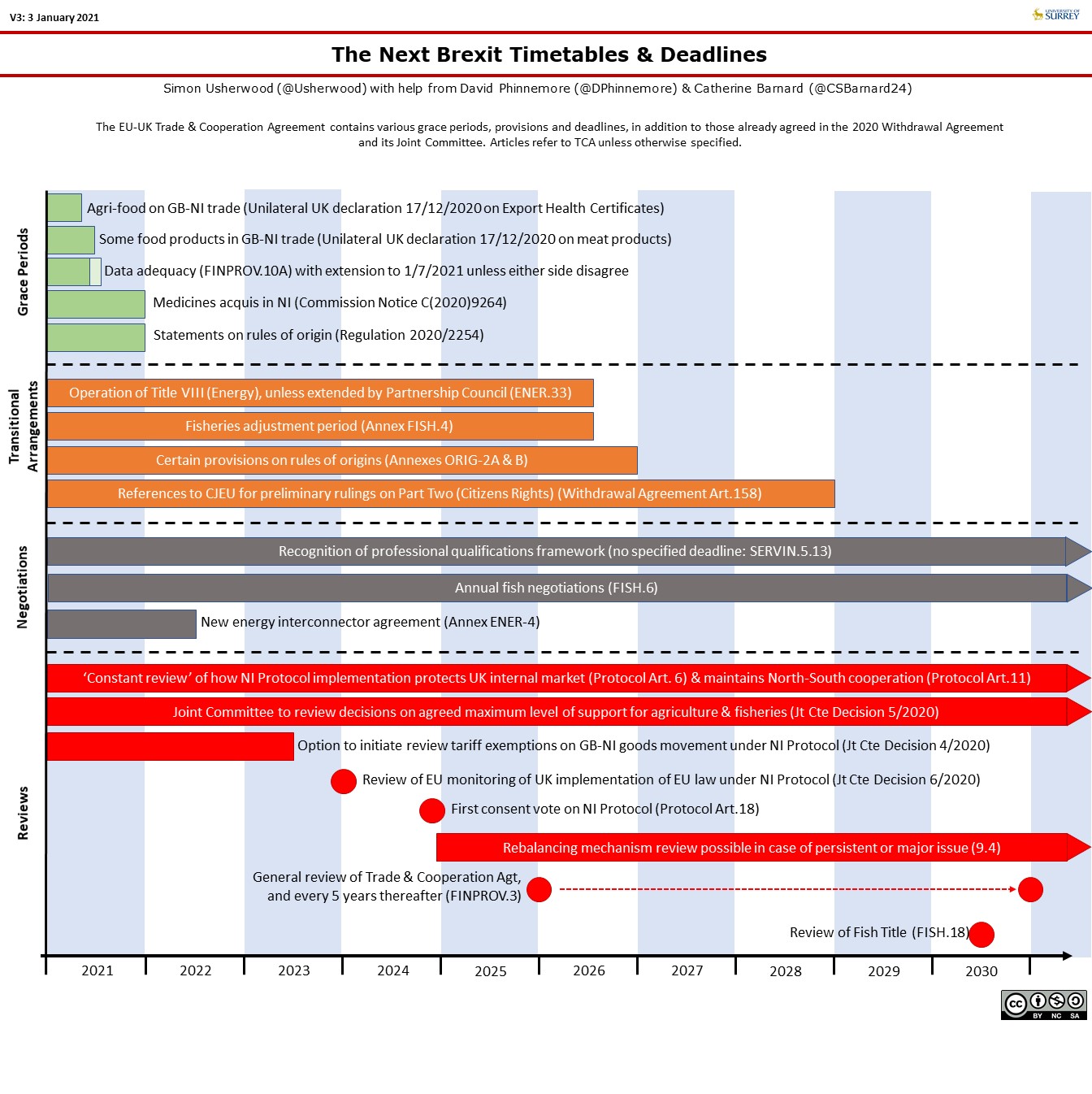

As the diagram above indicates, the TCA joins the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) in creating an architecture not solely of commitments but also of continuing change, review and negotiation.

Put simply, Brexit is not ‘done’, merely shifted into a new framework.

To illustrate the dynamic nature of the relationship, we might usefully consider four distinct areas.

Firstly, the TCA /WA creates a number of grace periods. These are agreed non-applications of rules or processes immediately after the end of transition/start of the TCA (i.e. 1 January 2021). In all the cases listed these are functions of the very rushed timetable from end of negotiations to start of implementation and the consequent inability of the UK to put in place replacement systems or processes.

Such grace periods should be considered relatively unusual, for the reason just mentioned: international treaties do not normally get done at such breakneck speed and they do not normally involve divergent regulation. This second point matters a lot in enabling a more phased introduction of the TCA model, since the starting point on 1 January was one of complete alignment on EU standards. The variable length of the grace periods is thus a function of the likely speed at which divergence and/or issues might be expected to emerge: higher for food standards (which involves health), lower for rules of origin (where integrated supply chains cannot change speedily).

A further should be made on the data adequacy provision in Art.FINPROV.10a, both for its semi-automatic extension and for the particularity of what follows. Unlike the other cases, where the UK will simply start following pre-agreed rules, this will require the EU to make a new unilateral declaration on adequacy for the UK to maintain existing data flows. This does not allow for any negotiation by the UK, only demonstrating its continuing implementation and enforcement of the necessary standards. The Commission did leave this hanging over the UK during the autumn, so it would be naïve to expect it to be without problem this summer.

The second category is that of more conventional transitional arrangements. Unlike the grace periods, these allow for temporary situations to apply while more major adaptations can take place.

In the case of references to the Court of Justice on citizens’ rights matters, the emphasis is on sunsetting this legal avenue, as free movement of people becomes a more historic right: the anticipation is that eight years should be long enough for any significant issues to have worked their way through to the courts.

By contrast, both the rules of origin and fisheries transitions are designed to phase in new arrangements in a more progressive manner than a simple step-change: the adjustments allow for a longer process of change that better reflects the ability of each side to operationalise it.

The final transitional arrangement is the limited shelf-life of Title VIII (energy) of the TCA. While it can be extended beyond June 2026, by mutual agreement, the Title also clearly sets out plans for further, specific negotiations, notably to implement a new energy interconnector agreement by the middle of next year. This is best understood as an early case of the two sides identifying specific needs for resolution, but not being able to tie that off straight away: thus Title VIII will grow, rather than shrink, over time, whether within the TCA text or not.

The interconnector example is the only specific and scheduled case of the third category: negotiations. The commitment to develop a new framework for mutual recognition of professional qualifications is left hanging in the TCA and there appears to be no sign of any immediate urgency to get this moving.

The other case of a commitment to negotiate falls under the fisheries section of the TCA. Annual rounds of discussions will continue using the Common Fisheries Policy framework through the 5.5 year adjustment period, using the TCA’s indications on reducing the EU’s share of access to UK waters. Thereafter, from 2026, the UK will be treated like other fishing states, albeit with one major caveat, namely that the EU can apply tariffs on UK fish if it suffers further reductions in its share (Bryce Stewart explains more).

With the exception of the fisheries negotiations, all that has been listed so far has been about bedding into a new relationship, but this is not the end of the structuring of relations.

Perhaps most consequential of the four categories is that of review, since these all carry the potential for more major changes to the TCA/WA arrangements.

Most fundamentally of all, the TCA carries a general review clause (Art.FINPROV.3), first at the end of 2025 and then every five years thereafter. No limits are placed on that review and so we might expect it to become a convenient point for both sides to (re)consider what they do with each other and how.

The timing of that first general review also matters, since it will follow the outcome of the first consent vote on the Northern Irish Protocol, the start of the emergency brake provisions in the UK’s Trade Scheme, and will coincide with the end of the fisheries adjustment period. Each of these might generate significant issues that require more general attention in the general framework. A similar bunching occurs in 2030, when the TCA’s provisions on fish will be specifically reviewed just ahead of the second general review.

All of this runs alongside the rolling reviews that the WA’s Joint Committee will be pursuing in its Northern Irish Protocol implementation (as specified in its recent Decisions). As the graphic at the top suggests, it might be expected that the TCA’s Partnership Council also ends up establishing such reviews, as it gears up its work and identifies points of interest.

Summary

While the signature of the TCA might have brought to a close of the ‘hot’ phase of Brexit, it certainly does not mean that the UK and EU have now entered a stable new relationship.

At best, the TCA/WA is a framework within which both parties will have to actively work to establish new norms of interaction and (hopefully) rebuild some of the trust that was lost during the period since 2016.

If the cataloguing above appears extensive, then that is because both of the time-constrained nature of the TCA negotiations and because of the continuing uncertainty of the UK about what it wants to do with its new situation. Only with the passage of time will it become evident how that fits with (or changes) the TCA/WA.