I’ll be straight with you: today is probably my favourite day of the Christmas season. I like it because it’s not a holiday and hardly anyone notices it, but mainly I like it because it’s the shortest day of the year.*

It’s a reminder that not matter what else might be dispiriting about this time of year – the weather, the present-based anxiety, the vague feeling that you haven’t hit your goals for the year – tomorrow will be a bit brighter, for a bit longer.

I mention this because it’s not how I normally think about the world around me. Specifically, it’s a recognition of a cyclical pattern that is essentially immutable (sure, I could become a global traveller, residing the southern hemisphere, but frankly, who’s got the energy?): it’s why late June is always a bit disappointing for me.

There’s a certain comfort in cycles, in watching the world carry on without our help or involvement. The certainty that the sun will rise again gives solace to those in the dark, just as the budding of the plants in spring brings a brightness into our lives.

But this natural world is not the only world in which we live. Indeed, most of our existence is spent in a human world, one constructed by us.

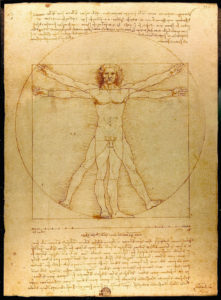

In the pre-modern era, natural metaphors abounded, from Aristotle’s circle of political forms to Benedict Anderson‘s identification of time as a circular, rather than linear, dimension. Even since, the notion of cyclical behaviour and patterns has not disappeared, but it is certainly much more limited.

Instead, we now see the world as a place to exist, under political and social systems that we design and build to whatever pattern we chose. Even if you take a historical institutionalist approach, as I do, and see that the dominant force shaping how things will be as how things are now, then still the potential for change is there.

As my former colleague Maxine David would rightly interject here, this where the structure-agency debate comes in: how are we bound by ‘the system’ and how much can we actually effect as change by ourselves? Such a world-view does not insist on circularity – the structure might be homestatic, but that does not presuppose that we eventually come back to where we started.

This year has been a case in point for all of these reflections. We have seen major political upsets – in the sense of running against the conventionalities of political science and ‘informed debate’ – in the UK and the US, alongside a burgeoning sense across the international system that the liberal certainties of the post-WWII period are not, actually, that certain.

In particular, the rupture created by the UK’s EU referendum points to both the potential for change – both short- and long-term – and the capacity for the structure to reassert itself. As I’ve argued repeatedly here, we should remark on how much has stayed the same as on how much things have changed. The shiny wrapping on the new Christmas presents shouldn’t distract us from the re-emergence of the same old jokes in the crackers or the revisiting of old family dynamics as we carve the turkey.**

It seems to me that there are essentially two responses to the referendum. The first is to complain. The process wasn’t fair, the other lot cheated and lied, people didn’t really understand, it’d be different if we did it again.

The second is to own the result. I don’t personally believe that the result ‘means’ anything – it was a combination of factors and motivations, possibly unique to each individual voter – but I can point you to a big bunch of people who can tell that it was ‘actually’ about X or Y. Theresa May’s first appearance before the Commons Liaison Committee yesterday was just the latest in a very long line of such pronouncements.

If we want to put a spin on this, then we might argue that these are two paths to the same destination: holding power to shape what happens next. Those trying to own the result are taking the direct route, grabbing the levers of power that present themselves. Those complaining are going the long way round, ultimately looking to change what those levers actually do.

The reason that complainants want this is that they are typically more liberal in their approach, which has served them very well over the decades: the system was made in their image and was supposed to avoid such calamities (I paraphrase, very slightly). Their reliance on the deep structures of the liberal democrat state meant that they ceded the ground on the specifics of particular political events.

Indeed, you could argue that eurosceptics have played the long game too, progressively building up the pre-conditions to enable their ultimate success: securing support in different parts of the system, opening up (and closing down) lines of argument and options, defining the language and framing of debate. To reference Dan Hannan, David Cameron’s decision to backtrack on a referendum on the Lisbon treaty meant that he was then only going to be able to subsequently offer an in-off vote further down the line.

Of course, the risk in such readings is no longer that of circularity, but of teleology: the idea that we are heading somewhere particular.

Possibly my biggest political lesson of recent years was when I gave a talk on the EU to a group of seniors. A member of the audience observed that we couldn’t trust the French, “after Crecy and Agincourt.” I retorted that I saw no link that what our forefathers did hundreds of years ago and what we do now, and that I wasn’t a slave to history. His response was simply that he was thus enslaved.

Much as I love the solstice and the passing of the seasons, I cannot accept inevitability in human affairs. Yes, the past does inform the present, but it does not command it. As we enter 2017, we should remember that nothing is given and nothing is fixed.

That should be both concerning and encouraging. Concerning, because it means we can’t take things for granted. Encouraging, because it means we have agency, we have the means to improve our lot. In the tussle between owning the system and shaping the system, we need to recall that the two work together: ownership is ephemeral without shaping, but is also the gateway to that shaping.

To illustrate this, consider this article (via a friend on Facebook). I’m not sure I agree with all the points, but the thrust is what matters more – things do change, often without our noticing or appreciating.

In short, the world of politics is ours – all of ours – to shape and mold. But if we don’t do that shaping and molding, then somebody will do it for us.

Which is why I am determined to head into the new year ready to make my voice heard. Join me, whether you agree with my views or not.

* – OK, the day with the shortest daylight hours, as the more pedantic members of my family like to remind me. But you know what I mean.

** – I do actually like Christmas BTW, despite everything I’m writing here.