Narrative arcs seem to be figuring in my life quite a lot at the moment.

On the one hand, I’ve just started watching House of Cards and can already see the arc of Frank Underwood’s trajectory being sketched out: the initial pique, the considered revenge, the rise and – I presume – the ultimate hubris. Partly I see that because I remember it from the first time around and partly because that’s what people do: make sense of what they see.

And this is the other hand. For my work with our Liberal Arts & Sciences students, we’ve been considering how people think and learn, and particularly the heuristics and shortcuts they employ in so doing. Partly that’s about System 1 & 2 processes, and partly it’s about the particular bent that people have of telling stories, both to themselves and to others.

All of this feeds into a key part of current debate about the European Union and its future: what’s the story we’re telling here?

Before anyone leaps up to complain that politics isn’t story-telling and is much more fundamental/rational/whatever, it’s worth developing the point that story-telling isn’t the same as saying it’s only about the story. Instead, the story is a way into understanding what is happening, a sense-making device. And stories can be more or less coherent and overt: one might even go so far as to say that whenever we talk about ‘values’ we are actually articulating a story about ourselves and what we are like. Just as religion provides a story about who we are, why we’re here and what life means, so too do stories provide a structure to politics.

So let’s consider the EU’s narrative arc. Right now, it seems that two options present themselves.

The first is the story of the triumph over oppressive nationalism and the discovery of our common humanity. The ‘peace in Europe’ narrative – the emergence from the ruins of war, the fight to create and develop joint institutions – has been the dominant one in EU circles for a long time. Even in recent years, we find echoes of it in the crises that the EU has faced, with those challenges being portrayed as just the next step in the struggle to achieve an ever closer union. In this version, Benedict Cumberbatch is Jean Monnet and Eddie Redmayne is Altiero Spinelli, making barn-storming speeches to the reluctant politicians, even as they profess their deep love for Europe’s common destiny to their families and friends. Gerard Depardieu becomes Helmut Kohl, personally travelling to the Berlin Wall, to smash the first hole through it and join hands with his long-lost brother on the other side. You get the idea.

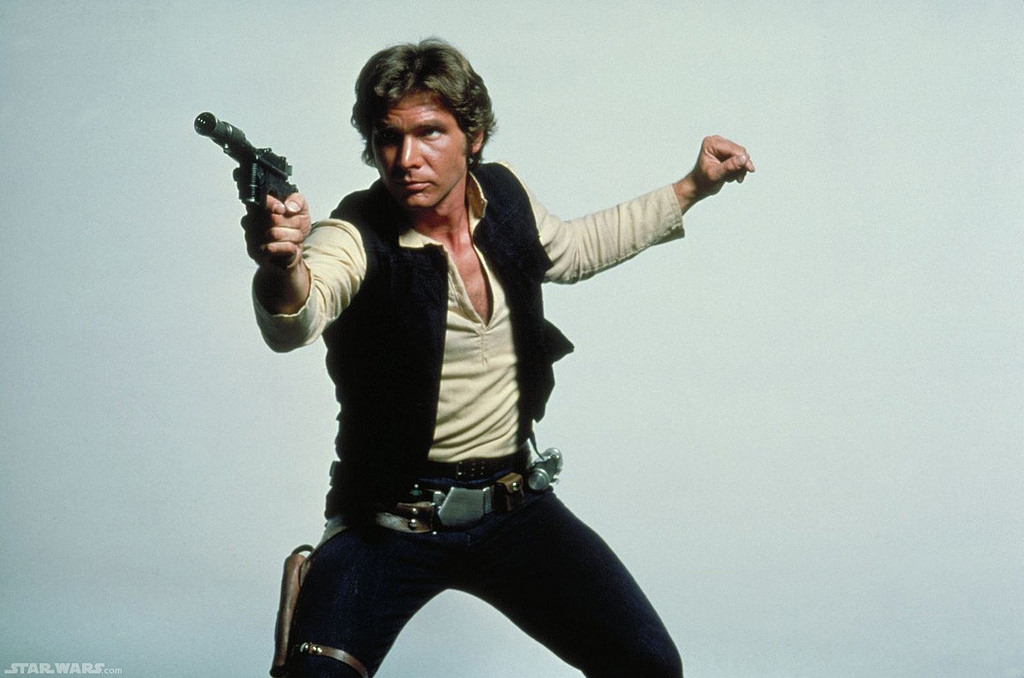

But you’ll also get the other narrative, that of the rebellion. Here it plays out something like Star Wars. There’s an oppressive political system, that we were tricked into accepting and which now tolerates no opposition. A plucky band of those who remember the old ways take up arms and fight, against all the odds, before ultimately winning out. Brad Pitt is Nigel Farage is Hans Solo, cocky and irreverent of authority, but a skilled combatant, getting right into the heart of the Death Star before blowing it up. Helen Mirren is Margaret Thatcher is Admiral Ackbar, making barn-storming speeches to the blindsided politicians, even as she professes her deep love of liberty and self-determination to Dennis and coordinates the resistance’s attacks. I think this also makes Robert Kilroy-Silk into Jar-Jar Binks.

I exaggerate, but only a bit.

In both cases, the story is the familiar one of overthrowing the past and discovering (and realising) a new, better future: the difference is the one of where we start and what we hold to be important.

Of course, both of these stories are unsatisfactory (quite beyond my dubious casting choices), because they are self-evidently not the other ones possible. In particular, the ‘out with old, in with the new’ approach strikes me as rather Hollywood, in it’s depiction of good and bad.

There is another story we might tell, where reconciliation is the theme, a meeting of minds and a recognition of the value of different approaches. Maybe we call this the ‘Mandela’ story, with someone coming through difficult times and events to bring together a divided community in harmony.

I’ll leave to you to decide who’s the Mandela in that one.