Earlier this week, I was quoted in a Daily Telegraph piece about Grassroots Out (GO). The article had noted that ten seeming-offshoots of the group had been registered with the Electoral Commission as participants in the referendum campaign. If the Commission were to consider them as separate, then taken together they would be free to spend as much as Vote Leave – the designated lead group. However, all ten seemed to fall foul of the restrictions placed on them in this regard, since they appeared to be attempts to divide up campaigning activity to different regions and audiences.

While some further response is awaited from the Commission on this, I have been interested to explore this a bit more. To put my cards on the table, this was something that I’d only half-noticed at the time and on which the Telegraph approached me for comment after their investigation, and my interest is not about trashing Grassroots Out (as you’ll see), but rather about understanding their strategy in this.

As a little bit of background, it’s useful to note that GO itself was set up in no small part as a means for Leave.EU to reposition itself in advance of the designation process by the Electoral Commission. Leave.EU was seem as too closely linked to Arron Banks – and, by extension, to UKIP – to be a viable cross-party platform, so GO was established as a more streamlined debating platform for public events around the country, in which it has been generally successful. Indeed, it should be recalled that it was GO, rather than Leave.EU, which submitted an application to the Commission for designation. That submission was made for the deadline at the start of April, with the result being made known on the 13th.

From the evidence I’ve been able to pull together, GO has been engaged in the creation of sub-groups since early March. I’m taking the use of the standardised naming and branding as a marker of being a sub-group here. As the table below indicates, the first of these groups – Labour GO – set up shop on both Twitter and Facebook. A week later, in mid-March, a block of groups came into being. Together, these sub-groups have been the most active, not only in the volume of online activity, but also in the number of mentions made of them by GO itself on their main Twitter feed. So far, so obvious: segmenting messages makes sense in a referendum campaign, to hit different audiences rather than going for the lowest common denominator.

However, from the last week of March there has been a further creation of sub-groups, carrying through to April, with the most recent addition coming only two weeks ago. These groups have been characterised by much less online activity and few, if any, references to them by GO.

| Group Name |

EC registered? |

Earliest Tweet |

First Facebook post |

Earliest mention by GO |

| Health Professionals GO |

X |

N/A |

– |

|

| Left GO |

X |

N/A |

– |

|

| SNP GO |

– |

– |

– |

|

| Labour GO |

X |

8/3/16 |

4/3/16 |

13/3/16 |

| Wales GO |

15/3/16 |

15/3/16 |

15/3/16 |

|

| Students GO |

X |

15/3/16 |

22/3/16 |

16/3/16 |

| Business GO |

X |

16/3/16 |

– |

16/3/16 |

| Scotland GO |

16/3/16 |

23/3/16 |

16/3/16 |

|

| Conservatives GO |

X |

17/3/16 |

23/3/16 |

17/3/16 |

| Lawyers GO |

18/3/16 |

– |

25/3/16 |

|

| LibDems GO |

21/3/16 |

– |

||

| Fishing GO |

24/3/16 |

– |

24/3/16 |

|

| Farmers GO |

24/3/16 |

– |

||

| NHS GO |

25/3/16 |

– |

25/3/16 |

|

| Northern Ireland GO |

X |

25/3/16 |

23/3/16 |

25/3/16 |

| UKIP GO |

25/3/16 |

23/3/16 |

25/3/16 |

|

| Teachers GO |

26/3/16 |

– |

– |

|

| TUV GO |

26/3/16 |

29/3/16 |

– |

|

| Trade Unions GO |

26/3/16 |

29/3/16 |

27/3/16 |

|

| Greens GO |

29/3/16 |

24/3/16 |

29/3/16 |

|

| Communists GO |

29/3/16 |

24/3/16 |

29/3/16 |

|

| Steel GO |

X |

30/3/16 |

– |

30/3/16 |

| Respect GO |

31/3/16 |

29/3/16 |

– |

|

| Scientists GO |

4/4/16 |

– |

12/4/16 |

|

| Gibraltar GO |

X |

4/4/16 |

– |

12/4/16 |

| LGBT GO |

X |

5/4/16 |

– |

7/4/16 |

| Veterans GO |

7/4/16 |

– |

7/4/16 |

|

| Liverpool GO |

13/4/16 |

– |

– |

|

| DUP GO |

25/4/16 |

24/3/16 |

– |

A quick glance at the names of the sub-groups will highlight the very heterogeneous nature of their target audiences: parties, social groups, regions, industries. This suggests less of a masterplan than a concentration on perceived areas of strength and traction.

The confusing part of this comes with the Electoral Commission registration. One might expect that the strongest, most active groups would be the ones to be submitted, purely because that’s the object of the exercise. However, as the next charts show, this hasn’t happened.

The first chart plots the start of Twitter activity by the sub-group against the number of times it’s mentioned by GO’s Twitter feed (either directly or by retweet). As you’d expect, older groups get more mentions. However, the registered groups (circled in red) seem to be pulled at random from the long list: the exclusion of Wales GO and Greens GO (with 31 and 12 mentions respectively) looks odd, given their relatively close relationship with GO.

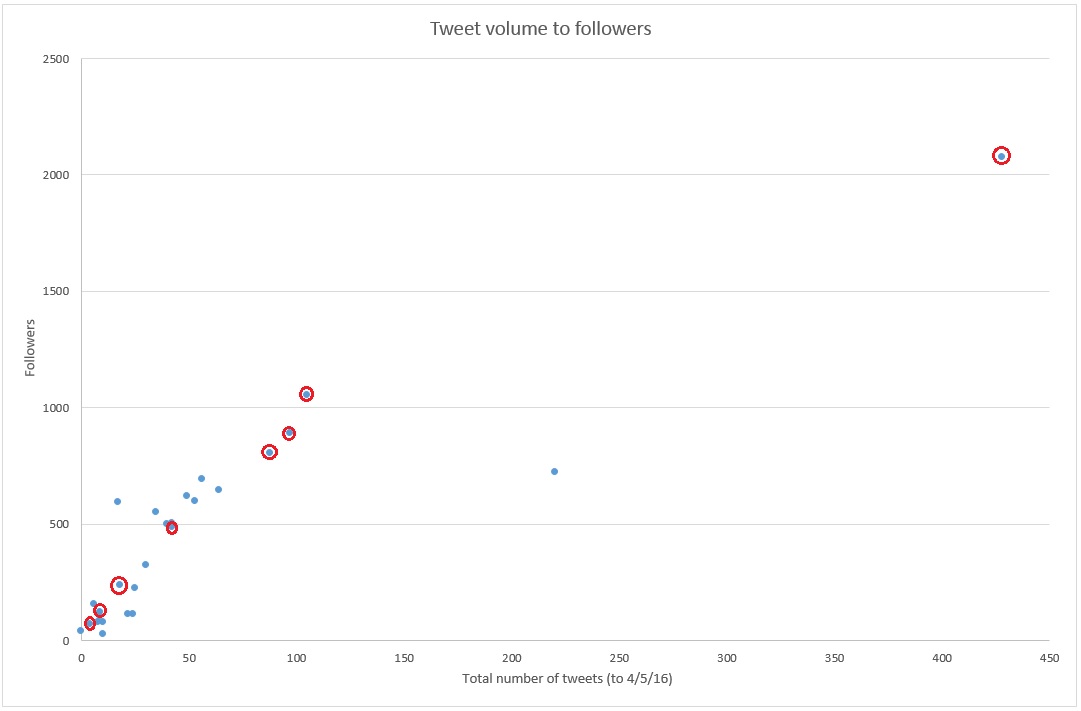

This mismatch is even more evident in the second graph which combines the volume of tweets since foundation to then umber of followers: again, the more one tweets, the more followers one gets. Again, there seems to be no match between registration and performance to date.

While the sum total of Twitter followers of the sub-groups nearly matches that of GO itself (12,380 to 13,821 as of yesterday), that contains a degree of duplication of followers, so the gains of more specialised audiences will be off-set by a reduction in volume. All of which raises a question about whether this is a productive strategy, quite aside from the regulatory question that we starting from.

The final twist in the tail concerns GO itself. Its website is now down, even if its Twitter and Facebook pages continue to produce content, and group members are still giving interviews. As part of our work on social media tracking during the campaign, we have noted that there has been a wind-down in GO’s activities in recent weeks, which doesn’t seem to be matched by a ramping-up of the sub-groups’ work. In short, GO seems to be stuck in a limbo, without a clear way out.