The theme of this year’s LGBT+ History Month is ‘Behind the Lens’ which invites us to celebrate the influence and impact of LGBT+ individuals to film and cinema from behind the camera rather than in front of it.

This topic gives us the ideal opportunity to share material from our extensive dance collections. For this blog we have decided to highlight a selection of women dancers and choreographers from the LGBT+ community who have made notable contributions to the world of dance, performance, and film.

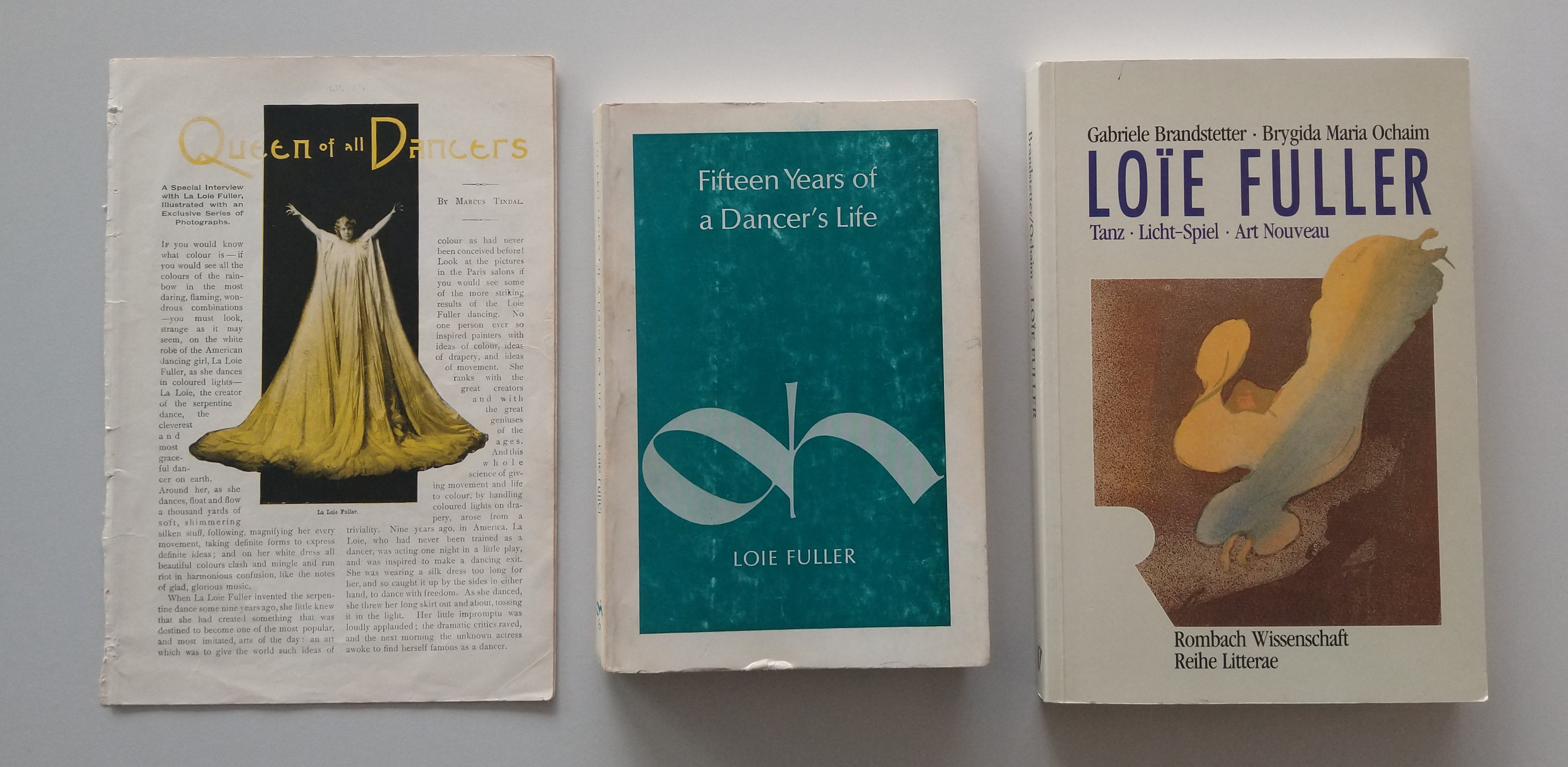

Loïe Fuller (1862-1928, birth name Marie Louise Fuller)

Even if you are not directly aware of Loïe Fuller’s work in dance and film you will have no doubt seen some of the many Art Nouveau artworks she inspired. The flowing movements of her voluminous and graceful costumes have become synonymous with the decorative style.

Loïe is credited with inventing a whole new style of dance. A special interview with Loïe Fuller written by Marcus Tindal titled ‘Queen of all Dancers’ in Pearson’s Magazine (1901) records how this new way of dancing came about:

‘Nine years ago in America, La Loie, who had never been trained as a dancer, was acting one night in a little play, and was inspired to make a dancing exit. She was wearing a silk dress too long for her, and so caught it up by the sides in either hand, to dance with freedom. As she danced, she threw her long skirt out and about, tossing it in the light. Her little impromptu was loudly applauded; the dramatic critics raved, and the next morning the unknown actress awoke to find herself famous as a dancer.’

Loïe perfected and refined the dance which came to be known as the Serpentine Dance. She also devised a costume incorporating curved wands and specified how the garment should be made. This innovative design enabled the performer to create sweeping movements to emulate different styles of wings.

She obtained patents for the design of her costumes (which were integral to the illusion she created on stage), as well as for the lighting techniques which added to the spectacle of the performance, and the enchantment of the audience. Details of two of these patents are given below:

Patent no. 518347. Patented April 17, 1894 ‘Garment for Dancers’

My invention relates to certain new and useful improvements in garments particularly adapted for theatrical dancing and more particularly adapted to that class of dancing known as ‘the serpentine dance’

‘My invention consists of certain improvements hereinafter fully shown and described, which improvements materially assist the dancer in posing, and, in causing, by movements of the body, the folds of the garment to assume variegated and fanciful waves of great beauty and grace’

Patent no. 533167. Patented January 29, 1895 ‘Theatrical Stage Mechanism’

‘My invention consists in constructing a new and useful theatrical stage mechanism to be used in the production of a dance, said mechanism having the effect of multiplying the reflections of one or more dancers performing in front of said mechanism. Thereby producing to the eye of the spectator an illusionary effect.’

‘In a modification of my invention I provide a series of vertical lines which give the effect of many pillars of fire around, and among which the figures are represented as dancing.’

Following Loïe’s death in early January 1928 an article in the Wilkes-Barre Evening News, (January 28, 1928) with the title ‘Loie Fuller’s work will be carried on by intimate friend’ stated that “Many new ideas in motion picture photography accomplishing weird and unnatural effects were discovered by Miss Fuller.”

The intimate friend referred to in the headline was Gab Sorère (1870-1961, born in France as Gabrielle Bloch) who had been the partner of Loïe for 30 years. Gab Sorère was quoted in the article as saying “By carrying on with her work the memory of Miss Fuller will be better perpetuated than it could be by the erection of stone memorials”

Loïe and Gab worked together to not only create theatrical performances, but also in the making of three films; Le Lys de la vie (1921), Visions des rêves (1924) and Les Incertitudes de Coppélius (1927). Of these, Le Lys de la vie is the only film to survive.

Loïe’s dances were much imitated by other performers, so it unfortunate that no footage of Loïe dancing seems to have survived. However, a film by Auguste and Louis Lumière dated 1896 of the ‘Serpentine Dance’ featuring an unknown performer still exists. The film was hand tinted in an attempt to recreate the lighting effects used on stage and this provides us with a glimpse of the sensation that was Loïe Fuller.

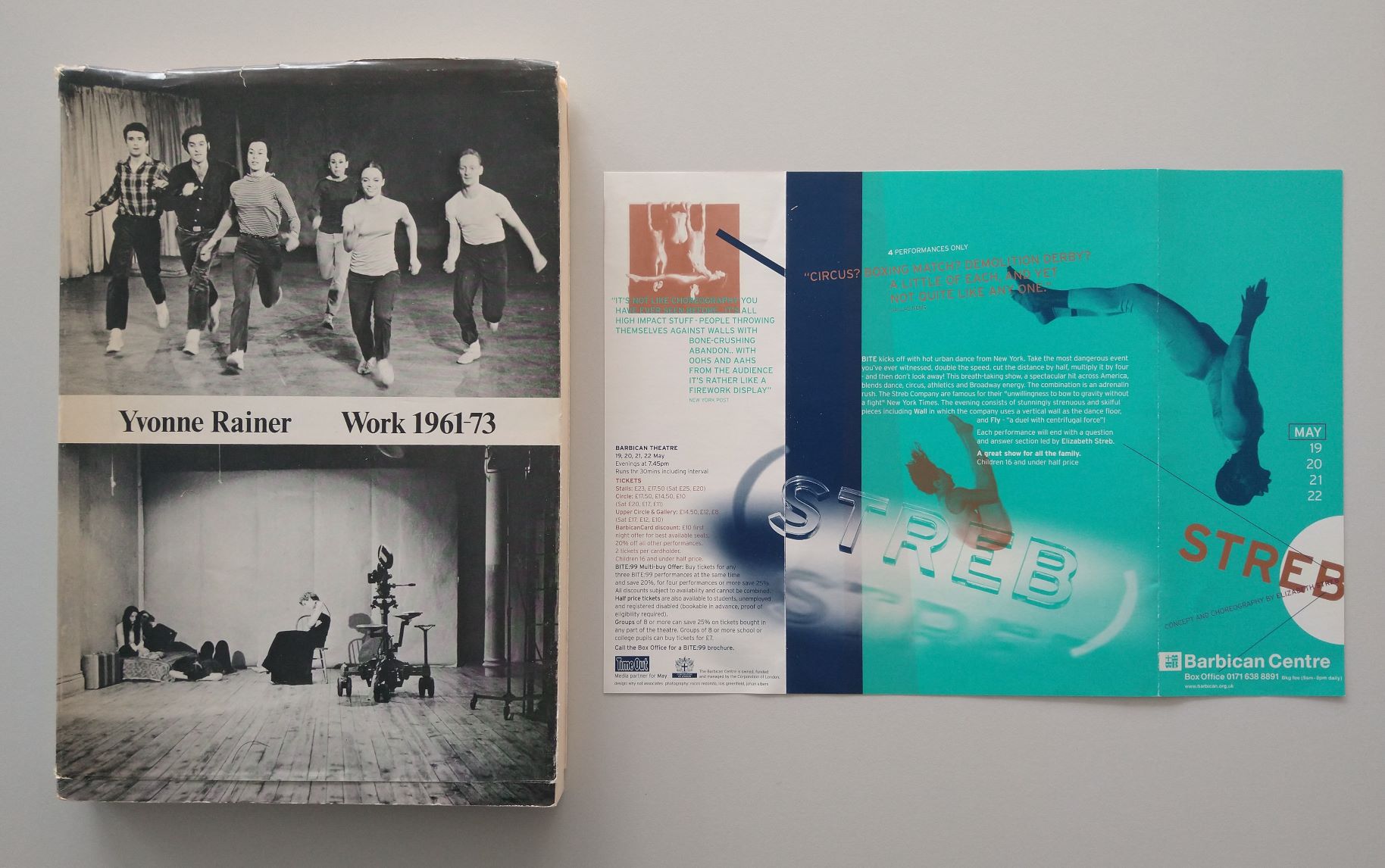

Yvonne Rainer (born 1934)

Yvonne Rainer started her career in performance as an actor but after being told that she ‘couldn’t generate the proper illusion’ and thinking objectively about her skill as an actor she came to the conclusion that perhaps this wasn’t the career for her.

After taking dance classes with the initial aim of improving her acting, she loved dance so much she decided to drop the acting classes and started studying dance in earnest. She appeared in many dance performances but felt that she was unlikely to be accepted into any professional dance company. She was also conscious that her body shape did not conform to the popular image of the female dancers of the 1950s and 1960s so if she was to remain committed to dance she would need to create her own work, and the intention of becoming a choreographer started to develop.

Initially her first use of film was to incorporate short filmed sequences into dance performances, but in the early 1970s she moved away from choreography and started to direct experimental feature length films:

- Lives of Performers (1972)

- Film About a Woman Who (1974)

- Kristina Talking Pictures (1976)

- Berlin/1971 (1980)

- The Man Who Envied Women (1985)

- Privilege (1990)

- MURDER and murder (1996)

In 1999 Mikhail Baryshnikov invited Yvonne to choreograph for his White Oak Dance Project and this resulted in her return to choreography. In an interview with the LA Times (21 June 2009) she stated ‘I’ve come back to the body as the main element of my work. Once a dancer, always a dancer, I suppose,’

In the winter of 2010-11 the BFI in London held the first UK exhibition dedicated to her career. It featured three of Yvonne’s works in the BFI Gallery and was accompanied by screenings of her seven full length films. The films have been restored in 4K by the Museum of Modern Art and the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation.

Rainer’s choreographic works are still highly influential and have been referred to as ‘anti-dance’ as they incorporated movements that were considered ordinary, such as running and walking. Without having an awareness of the complex motivations and background to her dances some have commented that Rainer’s choreographed pieces look like ‘ballet being done badly’. However, Yvonne’s work in both dance and film has much greater depth, exploring subjects such as the male gaze, feminism, terrorism, political power, and lesbian sexuality.

Elizabeth Streb (born 1950)

Elizabeth Streb is a dancer and choreographer whose work endeavours to push the limits of the human body. Her innovative style of extreme action dance which Streb herself has named ‘PopAction’ incorporates ‘a fusion of dance, sports, gymnastics, and the American circus’. Performances often involve the dancers flying through the air or slamming into barriers.

Streb’s creative works are not set to music, and she is often quoted as saying that ‘music is the enemy of dance’. Without music the choreography isn’t restricted to a set rhythm and actions and movements can be unconstrained and spontaneous.

As with Yvonne Rainer, Elizabeth Streb has been defined as a ‘anti-dance’ choreographer but perhaps a more insightful way of thinking about the choreographed performances is to consider how they challenge our preconceptions and definitions of dance.

As part of the London 2012 Festival to celebrate the Summer Olympics taking place in the capital Streb’s Extreme Action dancers performed at London landmarks on the 15 July 2012, in event title ‘One Extraordinary Day’. The site-specific performances included bungee-jumping from the Millennium Bridge, performing on the spokes of the London Eye and abseiling down City Hall. The City Hall event featured three performers one of which was Elizabeth Streb herself.

In a detailed interview in the Evening Standard (21 June 2012) to talk about ‘One Extraordinary Day’, the interviewer discusses how not only Streb’s work defies categorisation, but that it is also true of her as an individual. Streb is quoted as saying:

“I’m a gay person who has mostly been closeted because I never wanted my sexual orientation to be first and foremost and have people think, ‘She’s just a dyke slamming into walls’,” she says. “I’m a feminist but it’s not my identity. I’m an action specialist and it’s not a practical thing to be!”

In an article in ‘The New Yorker’ from June 2015 titled ‘Rough-And-Tumble’ Streb’s influences and inspirations for her work are explored including her study of Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering photographs of animal and human movements. The article also includes quotes from an email written by Mikhail Baryshnikov:

‘Elizabeth’s work is fearless and complex. When I first saw it, I was puzzled about how it made me feel—what was it about? It’s an interesting question that I can’t ever answer completely—and perhaps it’s many answers all at once: Is it art to provoke? (Certainly.) Is it art to please? (Definitely not.) Is it art for survival? (Good question!)’.

In the same piece there is an observation regarding the roles of men and women in the dance works: ‘Unlike in ballet and modern dance, the women are effectively as strong as the men, and they do not occupy gender roles. A woman in STREB is just as likely to catch a man thrown into the air as a man is to catch a woman.’

Whether you feel Streb’s works should be categorised as dance or acrobatics or by another classification, perhaps still undefined, her work generates a response in the viewer either positive or negative, but it is always thought provoking.

We hope that by celebrating the lives of these trailblazing individuals for LGBT+ History Month it will inspire others to find out more about the lived experiences of LGBT+ individuals and communities.