By Professor Amelia Hadfield and Evie Horner[1]

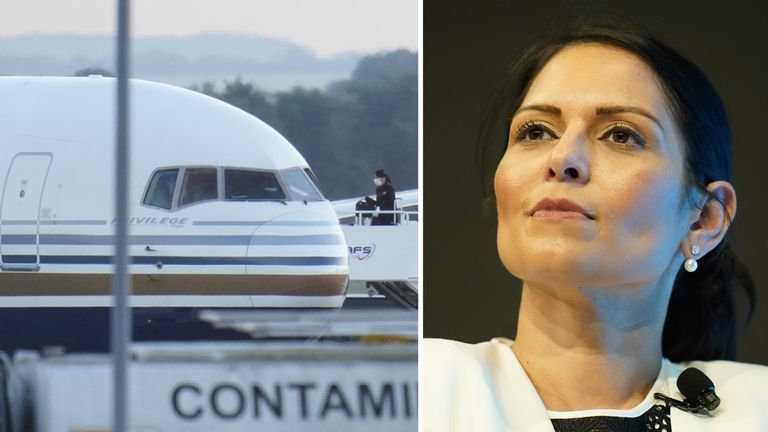

Tuesday 14 June 2022 saw Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s erstwhile “innovative approach”[2] to tackle illegal migration halted at the eleventh hour by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). 37 people were originally due to be on the inaugural Tuesday flight to Rwanda; however with previous legal challenges, this number was reduced to seven, before the flight itself was cancelled.

The Rwanda Asylum Seeker plan, announced on 14 April 2022, will focus on single men arriving to the UK via small boats and lorries, with the aim of reducing the number of migrants crossing the English Channel. On this basis, individuals who are deemed to have entered Britain unlawfully since 01 January 2022 could be relocated to Rwanda. Migrants who are ineligible for UK asylum and meet the relocation criteria will board chartered flights to the African country and will enter the Rwandan asylum system. Once individuals have arrived in Rwanda they will not be considered for return to the UK. If an individual chooses not to stay in Rwanda or their application is rejected, under the UN’s refugee charter, authorities will ensure their safe return to their country of origin or a third receiver country[3].

The ECHR is an international court, established in 1959, that protects civil and political rights which are established in the European Convention of Human Rights, which itself is a treaty drawn up after World War II. Pre-dating the EU, the ECHR has no EU links; however, it does form a part of the Council of Europe[4], of which the UK remains a member. A country’s withdrawal from the ECHR’s jurisdiction is an extreme rarity, with Russia the only country to have left following the invasion of Ukraine (alongside the temporary withdrawal of Greece in 1969).

On Tuesday 14 June 2022, the ECHR granted an urgent interim measure regarding an Iraqi asylum seeker due to be sent to Rwanda, which prevented his removal to Rwanda, until three weeks post-delivery of the final UK domestic decision in his judicial review proceedings[5]. This judgement in turn triggered further legal challenges and as a result, the removal of all seven passengers from the plane. In this specific case, the ECHR cited the UN high commissioner’s concerns that if refugees and asylum seekers are moved to Rwanda, they may not be able to access “fair and efficient procedures” related to their refugee status claims[6]. Interim measures such as these are rarely issued and are legally binding[7].

UK Migration Policy

UK migration policy has a long heritage of being incredibly sensitive, from dog whistle politics in the 2000s to the tinder box during Brexit, it continues to bedevil the approach and philosophy of both the UK as a state, and the Conservative Party itself.

Whilst the Leave campaign ironically won the 2016 referendum under the slogan “bring back control”, the UK has now lost the capacities provided by the Dublin III Regulation, an EU law that sets out which country is responsible for investigating an asylum seeker’s application. The legislation began back in 1990, known as the Dublin Convention, and reached its third iteration in 2013[8]. Prior to the UK’s departure from the EU, the UK was able to return asylum seekers to their first point of entry within the EU under this law[9].

The 2015/16 migrant crisis highlighted the EU’s failings to effectively deal with the issue of migration. Over one million refugees and migrants arrived in Europe by sea (unauthorised) in 2015[10]. With the majority arriving in Greece or Italy, this caused a major strain on the respective countries’ domestic asylum systems and in turn has caused a need to rethink the rules for redistributing asylum applications in the EU, set out under the Dublin III Regulation.

Although the Ukraine crisis has triggered a dramatic improvement in the treatment of Ukrainian citizens fleeing the conflict, the Russian invasion has exposed the contrast in consideration of non-European asylum seekers witnessed in the 2015/16 migrant crisis. With European governments opening their borders and citizens opening their homes in an act of solidarity towards Ukrainian refugees, there is hope that this could act as a turning point towards treating refugees more humanely in the future[11].

Now that the UK is not bound by the Dublin III Regulation, the Government has expressed an interest in bilateral deals with other EU countries in regard to returning asylum seekers to the EU without a replacement returns mechanism[12]. However, a number of EU member states such as France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands have already expressed that they do not intend to cooperate in such negotiations[13].

ECHR: Context and Options

At this point, a little context is in order. In 2016, Johnson described the European Convention on Human Rights as “one of the great things we gave Europe”[14], however, after the ECHR intervened this Tuesday, the Prime Minister hinted at the UK’s withdrawal, stating “will it be necessary to change some laws to help us as we go along? It may very well be, and all these options are under constant review.”[15] Jessica Simor QC, one of the country’s leading specialists in public/regulatory, EU and human rights law, took to Twitter to explain that “if the UK withdrew from the ECHR, the next step would be to leave the UN…it is a baseline – if you’re out you’re lining up with Belarus and Russia. Not a good look & bound to destabilise us even more.”[16]

The question at this point is what next. If the UK was indeed to consider withdrawing from the ECHR, what would the impact be? It’s certainly a point that’s been raised before. Prior to the 2016 EU referendum, Dominic Raab and Theresa May for example raised the option of leaving the ECHR. This would involve the repeal of the Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998, which incorporates the ECHR into domestic law, and replacing it with a British Bill of Rights[17]. In December 2021, the UK government launched a consultation on a new bill of rights to replace the HRA. Included in this proposed overhaul are key provisions limiting a category of individuals from escaping deportation on human rights grounds, the enhancement of press freedom of expression, the potential to trial by jury and the greater protection of public authorities[18]. Dr Katie Boyle[19] highlights that leaving two European systems could result in a human rights legal deficit. Whilst a British Bill of Rights could fill this void, Boyle argues that significant constitutional change necessitates a fair, democratic and lengthy deliberative process[20].

In 2021, the African Union announced that it is home to 85% of global refugees as opposed to just 15% hosted by developed countries[21]. On 14 April 2022, Boris Johnson made a speech on his plans to tackle illegal migration and stated, “our compassion may be infinite, but our capacity to help people is not.”[22]. Given Rwanda still ranks among the 20 poorest countries in the world in terms of GDP per capita, and 40% of its population lives below the poverty line, it remains highly questionable how the African nation has the capacity that the UK is lacking[23]. The ECHR ruling on Tuesday highlighted this very point. Whilst the UK was largely responsible for building the Strasbourg system of the protection of human rights, the current political landscape indicates that we could be the very nation that destroys it.

Government Options: Fillip or Foil?

The UK Government has therefore turned to Rwanda. Johnson’s description of the African nation as “one of the safest countries in the world”[24] is remarkable given the UK made allegations of extrajudicial killings, disappearances and torture in Rwanda at the UN last year[25]. Rwanda has already welcomed around 150,000 refugees from other African countries and approximately 70% of the nation’s already densely populated 13 million people are subsistence farmers which means they eat as opposed to sell what they grow[26].

Home Secretary, Priti Patel, has made it clear that the UK government will not back off from the Rwanda Asylum Seeker Plan, despite Tuesday’s cancelled flight already costing the UK taxpayer approximately £500,000[27]. The UK government continues to paint a false image of a compassionate Britain, evidenced by Priti Patel’s statement to the House of Commons on Wednesday, including the line that “we are a generous and welcoming country”. Whilst many words in the English dictionary are open to interpretation, sending human beings, of whom Refugee Council Chief Executive, Enver Solomon, highlights, are often those who have escaped war, violence, persecution and torture[28], to Rwanda, is not welcoming under anyone’s definition of the term.

[1] Professor Amelia Hadfield is Dean International and Head of Department of Politics at the University of Surrey, as well as the Founder and Co-Director of the Centre for Britain and Europe (CBE). Evie Horner is soon to graduate with a BSc in Politics with French from the University of Surrey and is a Studentship holder at the CBE.

[2] GOV.UK. (2022) PM speech on action to tackle illegal migration. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-action-to-tackle-illegal-migration-14-april-2022 (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[3] Sky News. (2022) ‘Why are migrants being sent to Rwanda and how will it work?’, Sky News, 14 April. Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/where-is-rwanda-why-are-migrants-being-sent-there-and-how-will-it-work-12589831 (Accessed: 19/06/2022).

[4] Founded in 1949, The Council of Europe is a human rights organisation that comprises of 46 member states. All members have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights which protects human rights, democracy and law. The European Court of Human Rights thus ensures the implementation of the Convention in all member states.

[5] Davies, C. (2022) ‘What is the ECHR and how did it intervene in UK’s Rwanda flight plans?’, The Guardian, 15 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/jun/15/what-is-the-echr-and-how-did-it-intervene-in-uk-rwanda-flight-plans (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[6] Dzehtsiarou, K. (2022) ‘Rwanda deportations: what is the European Court of Human Rights, and why did it stop the UK flight from taking off?’, The Conversation, 15 June. Available at: https://theconversation.com/rwanda-deportations-what-is-the-european-court-of-human-rights-and-why-did-it-stop-the-uk-flight-from-taking-off-185143 (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[7] Ibid.

[8] House of Commons Library (2019) What is the Dublin III Regulation? Will it be affected by Brexit? Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/what-is-the-dublin-iii-regulation-will-it-be-affected-by-brexit/ (Accessed: 19/06/2022).

[9] UK in a Changing Europe. (2021) ‘What is the Dublin Regulation?’, UK in a Changing Europe, 25 June. Available at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-facts/what-is-the-dublin-regulation/ (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[10] European Agency for Fundamental Rights (2016) Asylum and migration into the EU in 2015. Available at: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2016-fundamental-rights-report-2016-focus-0_en.pdf (Accessed: 19/06/2022).

[11] Venturi, E. and Vallianatou, A. (2022) ‘Ukraine exposes Europe’s double standards for refugees’, Chatham House, 30 March. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/03/ukraine-exposes-europes-double-standards-refugees (Accessed: 19/06/2022).

[12] UK in a Changing Europe. (2021) ‘What is the Dublin Regulation?’, UK in a Changing Europe, 25 June. Available at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-facts/what-is-the-dublin-regulation/ (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[13] Bulman, M. (2021) ‘Hundred of asylum seekers in UK being considered for removal to EU- despite absence of returns deals’, The Independent, 27 May. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/uk-asylum-seekers-deportation-returns-b1854858.html (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[14] Webber, E. (2022) ‘Boris Johnson rages at the European Court of Human Rights. But will he act?, Politico, 16 June. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/uk-boris-johnson-slams-the-european-court-of-human-rights-but-will-he-act/ (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Simor, J. [@jmpSimor] (2022) If the UK withdrew from the ECHR, the next step would be to leave the UN. The Council of Europe has 46 states in it, having expelled Russia in March. It is a baseline – if you’re out you’re lining up with Belarus and Russia. Not a good look & bound to destabilise us even more [Twitter] 15 June. Available at: https://twitter.com/JMPSimor/status/1536855790761426952?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Etweet (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[17] Boyle, K. and Cochrane, L. (2016) ‘Brexit and a British Bill of Rights: four scenarios for human rights’, UK in and Changing Europe, 17 May. Available at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexit-and-a-british-bill-of-rights-four-scenarios-for-human-rights/ (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[18] Fenwick, H. (2021) ‘Five takeaways from the UK government’s proposal to replace the Human Rights Act’, The Conversation, 15 December. Available at: https://theconversation.com/five-takeaways-from-the-uk-governments-proposal-to-replace-the-human-rights-act-173788 (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[19] [19] Boyle, K. and Cochrane, L. (2016) ‘Brexit and a British Bill of Rights: four scenarios for human rights’, UK in and Changing Europe, 17 May. Available at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexit-and-a-british-bill-of-rights-four-scenarios-for-human-rights/ (Accessed: 17/06/2022).

[20] Ibid.

[21] African Union. (2021) Press Statement on Denmark’s Alien Act provision to Externalize Asylum procedures to third countries. Available at: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20210802/press-statement-denmarks-alien-act-provision-externalize-asylum-procedures (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[22] GOV.UK. (2022) PM speech on action to tackle illegal migration. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-action-to-tackle-illegal-migration-14-april-2022 (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[23] Wohlfahrt, S. (2022) ‘Rwanda: Tackling the challenge of overpopulation’, France24, 06 May. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/reporters/20220506-rwanda-tackling-the-challenge-of-overpopulation (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[24] Syal, R. (2022) ‘Tens of thousands of asylum seekers could be sent to Rwanda, says Johnson’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/apr/14/tens-of-thousands-of-asylum-seekers-could-be-sent-to-rwanda-says-boris-johnson?utm_term=Autofeed&CMP=twt_gu&utm_medium&utm_source=Twitter (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[25] GOV.UK (2022) 37th Universal Periodic Review: UK statement on Rwanda. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/37th-universal-periodic-review-uk-statement-on-rwanda (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[26] BBC News. (2022) ‘Why are asylum seekers being sent to Rwanda and how many could go?’, BBC News, 16 June Available at:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/explainers-61782866 (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[27] Badshah, N. and Sparrow, A. (2022) ‘First UK deportation flight to Rwanda cancelled after European court intervention- as it happened’, The Guardian, 15 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/live/2022/jun/14/rwanda-flights-asylum-seekers-priti-patel-liz-truss-conservatives-uk-politics-latest (Accessed: 16/06/2022).

[28] Ibid.