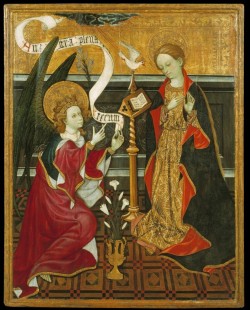

Artist unknown © public domain

March 25 is Lady Day, a traditional name in England for the Feast of the Annunciation. This feast commemorates Gabriel’s proclamation to Mary that she will be the mother of God (Luke 1: 26-38). After this event, when Mary visits her cousin, Elizabeth, Mary declaims a poem in praise of God – the Magnificat – of her own composition. The first Marian poem was authored, therefore, by a woman for a woman. In her lyric Mary predicts that ‘all generations will call me blessed’ and this has proven to be the case.

The list of medieval authors who have written Marian devotions is long. It includes Geoffrey Chaucer, William Dunbar, John Audelay, Osbern of Bokenham, John Gower, William Langland, the ‘Gawain’- poet, Thomas Hoccleve, John Lydgate and Osbern of Bokenham. The great and the goodly – the canon of medieval English literature – all turned their pen, at one time or another, to praising the Virgin Mary. Such evidence appears to support Barry Spurr’s view that most of the medieval authors of Marian poetry, with the exception of the ‘passing references’ by Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, were men (Spurr, 2007, p. 76). Spurr does cite ‘A hymn to the Virgin’ written by an anonymous anchoress of Mansfield as noteworthy but does so precisely because this woman is exceptional (p. 77). It would appear that subject matter too can be canonical.

As a role model for women, Mary – Virgin Annunciate, wife, Mater Dolorosa, Pietà, Heavenly Queen, and Intercessor – sets an impossibly high standard. Yet in spite of the differences between themselves and the Mother of God, medieval women, labouring in a tradition forged by literary forefathers, wrote, commissioned, owned and read Marian works. The Marian devotion of Eleanor Percy, Duchess of Buckingham (1474-1530), is illustrative of how secular women might engage with the Mother of God.

The Oratio Elinore Percie Ducissa Buckhammie [The Prayer of Elinore Percy Duchess of Buckingham] is a macaronic verse translation of the anonymous, Latin antiphon, Gaude virgo, mater Christi [Rejoice Virgin, Mother of Christ]. It is recorded on the final page of the Book of Hours, now British Library MS Arundel 318, copied probably by Anne Arundel (c. 1485-1552), Eleanor’s younger sister.

Image of St Catherine in British Library MS Arundel 318, f. 26v © The British Library

Eleanor’s work is that of a poet skilled in integrating Latin into Middle English sentence structure, as the following extract illustrates:

Gawde, Vergine and mother beinge

To Criste Jhesu, bothe God and Kinge,

By the blessed eyare [ear] him consevinge.

Gabrielis nuncio [by Gabriel’s message]

Gawde, Vergine off all humylytie,

Showinge to us thy sonnes humanitie

Whan he without paine borne was of thee

In pudoris lilio [in the lily of chastity]

The emphasis that Eleanor places on Mary’s motherhood through her own additions to the Latin original; ‘Showinge to us thy sonnes humanitie’ (stanza two), and that the fruit of Mary’s womb in Heaven ‘Shall still ther reigne everlastinglie’ (stanza seven), suggests that Eleanor recognised in Mary a similar pride of a young mother in ‘showinge’ her own ‘sonnes humanitie’ before an appreciative audience. As Eleanor’s prayer indicates, sisterhood with the Virgin was not simply the perception of those who took the veil.

Eleanor, Anne, and their elder sister Joan (1470-1547), may have been the first owners of this book of hours (made in the Netherlands in around 1490), that became a record of female-centred piety and a family heirloom. Eleanor was the grandmother of Anne Percy (c. 1485-1552), daughter of Eleanor’s son, Henry (the heir whose birth may well have inspired Eleanor’s Marian prayer). Anne was the second wife of William FitzAlan, eleventh Earl of Arundel and Lord Maltravers (c. 1476-1544), and her ownership of the book of hours after 1530 is recorded under her married name, ‘Anne Mautreuers [Maltravers] ys the tru possessor of thys boke’ (f. 153v).

In 2016, The Feast of the Annunciation falls on Good Friday in the British Isles. This also occurred on March 25, 1608, the rarity of which inspired John Donne to compose ‘Upon the Annunciation and Passion Falling Upon One day, 1608.’ In his poem Donne ponders the simultaneity of Christ’s conception and crucifixion, inspired by the constellation of the two feast days:

At once a Son is promised her, and gone;

Gabriell gives Christ to her, He her to John;

Not fully a mother, She’s in orbity;

At once receiver and the legacy.

About to be a mother, and also in a state of bereavement or ‘orbity’ for her child, Donne contemplates Mary’s liminality. All too many medieval women will have understood the paradox created when the feast of the Annunciation and the Passion coincided: of anticipating the birth that might also be the death of the child, and that of the mother herself.

While the convergence of the feasts of the Annunciation and the Passion is rare, medieval women’s literary responses to the Virgin are not as scarce as we have been led to believe. Eleanor Percy is only one of a number of women who followed in the footsteps of the first author of Marian poetry; none other than the Virgin herself.

Sue Niebrzydowski, Bangor University

4 April 2016 (The Feast of the Annunciation transferred from 25th March to first date post the Easter Octave)

Barry Spurr, See the Virgin Blest: The Virgin Mary in English Poetry (Basingstoke, 2007).

For the text of Eleanor Percy’s prayer see Women’s Writing in Middle English ed. Alexandra Barratt (Harlow, 1992), 279-80.