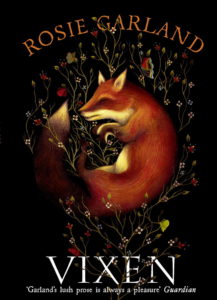

Credit line: Alex Allden at HarperCollins Publishers

Rosie Garland won the Mslexia Novel competition in 2012 and her debut novel The Palace of Curiosities was published in March 2013 by HarperCollins. Her second novel, Vixen, published in 2014, is set in the plague year of 1349. In this post, Rosie writes about writing a novel set in the medieval past.

******

I am fascinated by times when the world is on the cusp of massive change, specifically that moment before those changes take place. I view it rather like an indrawn breath, held and not released. Vixen is set during one such period of upheaval: 1349, the year the Black Death struck England. I wanted to capture that sense of a deadly force and its inexorable advance. In an isolated village deep in a forest in the south west of England, the arrival of a mysterious young woman – the Vixen – turns the lives of the villagers upside down. Amongst other things, the novel is about love found in unexpected places; the impossibility of escape if you won’t accept you are in a prison; how people refuse to see what’s right in front of them and the consequences of that refusal.

These are themes with personal resonance.

A very early memory is of my grandmother reading fairy stories. Magical elsewheres and elsewhens that transported me far away from childhood rural England. Which was, and is, a delightful place to be unless you are in any way different. This wasn’t restricted to sexuality – anything that wasn’t marriage and 2.4 children (preferably with one on its way by the age of 16) was regarded as deeply suspect. Suckled on the boundless possibilities of fairy tales, I grew up with a passion for medieval history, possibly because it too was elsewhere, other, and I yearned to get away. As a child, the Middle Ages was ‘The Black Shield of Falworth’on Sunday afternoon TV. In glorious Technicolor Cinemascope, it boasted bleached-blonde damsels in crimson lipstick, knights in neatly-ironed satin tabards and an awful lot of thwarting and jousting and choreographed sword fights. This was a Middle Ages where Tony Curtis proclaimed ‘yonda stands da cassel of my fadda’ in his salty New York accent (sadly apocryphal).

I learned this wasn’t the full story. Nurtured by inspiring teachers who introduced me to Chaucer, I found a perfect home at the University of Leeds with its specialism in Old and Medieval English. I fell in love with the cadence of Anglo-Saxon poetry, a dance of language that feels fresh despite being 1000 years old. Ever seeking the story, my undergraduate dissertation explored the parallels between Saints’ Lives and fairy tales (dear old Vladimir Propp & structural analysis). My MA was in Medieval Studies – not Creative Writing. My dissertation rejoiced in the title ‘The Apocryphal Elements in the Benedictional of St Aethelwold’, and combined art, politics, social history, faith and linguistics. I’m sure it sounds frightfully old hat, but in the early 1980s postgraduate study that drew together separate subjects was unusual. To my mind, the MS wasn’t produced in a vacuum, so it seemed nonsensical to study it in one. (As a sidebar, I was offered a doctoral scholarship to study the Lives of the Virgin Martyrs, but life has its odd bifurcations and I chose the path of singing in Goth band The March Violets).

However much I like to keep up with current research, I’m clear that my novels are not academic publications. Nor should they be. The two have different purposes, goals and styles. History on its own is not a story, let alone one that compels the reader to turn the page. One of the first questions I’m asked at book signings is how I do my research, as if that’s all that’s needed. My attitude is that it’s vital, but like high-fat food, best taken in moderation. Of course, I need to research the period assiduously. However, it’s essential to know when to stop. I am driven to distraction by novels in which the narrative comes to a juddering halt whilst the author goes off on a tangent about Babylonian cylinder seals (a prime example is Dan Brown. If you think I’m joking, check out).

The way I see it, the art of good research is when the reader barely notices its presence, only that everything feels right. Personally, I don’t care if an arrow is fletched with swan feather, eagle feather or magpie feather. I want to know who is shooting it, who dies, and why I should give a monkeys. A great example of a novel in which the history – pungent, gritty, humorous and ghastly – serves the story and characters rather than the other way round is Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. It had a profound influence on how I approach the writing of my own novels.

Dammit, Jim, I’m a storyteller, not a historian.

I don’t write the past because I regard it as quaint, safe and charming. When I encounter fictionalisations that portray people from ‘back then’ as different and one-dimensional (tropes of the simple peasant, saintly maiden, evil sheriff, chivalric knight etc), I switch off. I am at odds with the saw ‘the past is another country; they do things differently there’ (LP Hartley, The Go-Between, 1953). My personal conviction is that we haven’t changed much; that we share the same motivations. Love tastes like love and hatred like hatred, whatever era.

I don’t see myself as a historical writer, specifically. Not that I’ve a problem with the label – I’ve been called worse. But it’s where my characters and their narratives take me and in it I find a freedom to plunge into fictional voices. I link this to Emily Dickinson’s ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant’ and Michael Ondaatje’s assertion that one can be ‘more honest when inventing, more truthful when dreaming’ (Interview with Eleanor Wachtel, June 1994, Essays on Canadian Writing; Issue 53). The very phrase ‘historical fiction’ is something of an oxymoron; a dislocation of truth (history) and lies (fiction). I relish the dance of that tension.

Taking a step back in time can make it easier to see the trees, so to speak. Historical settings provide a sense of distance, which can be particularly handy when tackling difficult subjects. These are what motivate me. In addition to Plague deaths, Vixen also touches on domestic violence, misogyny, hatred of the outsider, child abuse, the urgency of brief lives and how fear can make monsters of good men. I’ve found that historical settings can act as a buffer between the reader and the grimness, as well as providing windows through which narrative light can shine. Light is as vital as darkness.

I have a penchant for sneaking things in beneath the radar. One of Vixen’s themes is how two women find each other. Anne is a young villager whose expectations run to husband, children and no further. Through her relationship with the Vixen she discovers love can transcend gender. However, they do not refer to themselves as gay, let alone queer (if there’s one thing I find more irritating than cod-medieval romps full of corsets and yea forsooths, it’s modern people in wimples).

In 14th century Europe, women’s sexuality was of such little importance there was no word for lesbian. The idea that women might have sex with other women was largely incomprehensible, for the simple reason that sex was dependent upon the presence of a penis. The fulminations of the church were almost entirely directed at men who practised sodomy ( (but see Judith C. Brown, Immodest Acts, OUP 1986; and The Lesbian Premodern, edited by Noreen Giffney, Michelle Sauer and Diane Watt, Palgrave, 2011). Whatever else fenced them in, Anne and the Vixen are not hemmed in by vocabulary.

One of the many pleasures of historical fiction is the opportunity to give a voice to those who don’t make it into the history books. A motif running through all my writing is that of the outsider; someone who won’t (or can’t) squeeze into the one-size-fits-all templates on offer and the friction that occurs when they try. It explains my choice of first person present tense for Anne and the Vixen. I wanted them to speak for themselves, rather than endure the ventriloquising that comes with third-person.

At heart, I’m interested in creating characters who are greedy, curious, yearning, silly, striving, hopeful, cantankerous, nurturing, disobedient, sneaky and self-serving. Characters with unrequited sexual desires because of guilt, self-denial, or fear of social condemnation. In short, characters who live and breathe and change; and as they change their desires change and develop too.

Rosie Garland