Hildegard of Bingen (c1098-1179) could be described as a Renaissance Woman long before that term was coined (for men) or the Renaissance dawned. She was a poet, musician, theologian, composer, artist, doctor, botanist, philosopher, environmentalist, singer, herbalist, preacher, lexicographer and visionary – and it would be no idle claim to call her an early feminist.

Hildegard was born in Rhineland and given to the Church when she was 8 years old. As an adult she became mother superior of her order at St Disibod, but having come into conflict with church authorities, she founded a new abbey at Rupertsberg near Bingen in 1150, taking many of her nuns with her. Although sometimes controversial and not above bitter arguments with clergy, she was enormously respected in her lifetime and, as well as preaching widely in Europe, she regularly corresponded with a number of popes.

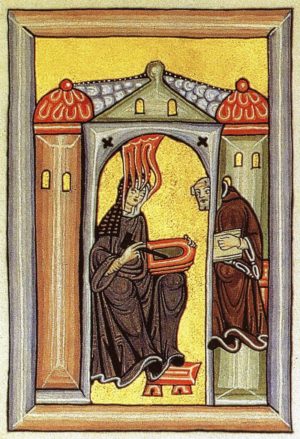

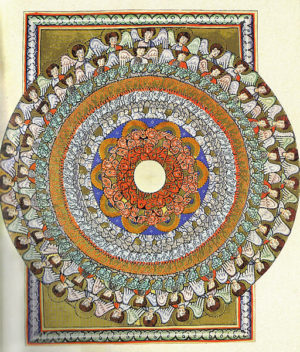

Her beautiful, ethereal music has grown in popularity in recent years, as well as some of her mystical art, which was inspired by her visions and set out in her major prose works: Scivias, Liber Vitae Meritorum and Liber Divinorum Operum. She also practised medical and herbalist sciences, transcribed her own music and invented her own script. Her medical knowledge was extensive, and although some of her prescriptions sound strange to modern ears, she is credited with having effected many cures.

This poem was written for a book about Hildegard, published in Italy in 2012 on the occasion of Pope Benedict XVI naming Hildegard a Doctor of the Church*. It also formed part of an exhibition of my poetry mounted in Winchester Cathedral when I was Poet in Residence for that city’s Ten Day Arts Festival in 2013. The poems were set in appropriate places all around the cathedral, and because of its subject matter, this one was placed below the pulpit.

Hildegard: Doctor of the Church

Hildegard believed that herbs for the body’s healing

had a part to play, with prayer, in the soul’s salvation;

and perceiving the greening of earth and heaven

from far beyond our human understanding,

she celebrated Viriditas, the force that flows

through all that’s green and good, in all that grows.

Like many other women since,

she posed a challenge to the Church,

displaying a deep learning never found

in books the clergy knew,

communicated in an alphabet they couldn’t read,

and if they could, they wouldn’t understand.

Down the centuries we hear her songs of glory

soaring higher in ripieno praise,

above the black-clad choir stalls

and dusty academic libraries

of those who failed to grasp that wisdom

could be grounded in a woman’s native wit.

As she joins the other doctors of the Church:

Térèse, Theresa, Catherine of Sienna,

along with sundry men, the question hovers:

will those without a voice today

nine hundred years from now be heard,

admired?

Alwyn Marriage

* Hildegard, Visions & Inspiration, edited by Gabriel Griffin, published by Wyvern Works, Italy, 2012.

Vision of the angelic hierarchy from Scivias 1.6.

Image from Wikipedia Commons