The results of a recent nuclear physics experiment featuring Surrey physicisits has just been published in joint papers – one in Physical Review Letters, and one in Physical Review C. The experiment, in collaboration with authors from 12 institutions, found the most extreme “octupole” shaped nucleus to date. The nucleus in question is an isotope of Gadolinium (element 64).

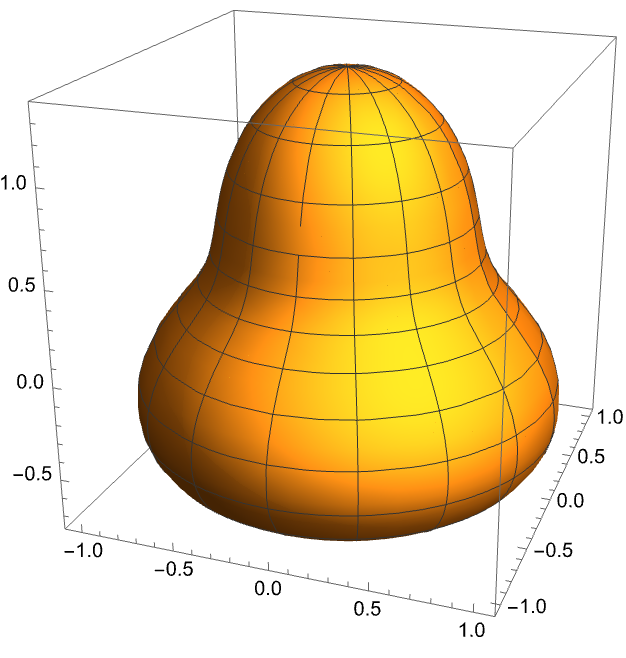

Many nuclei are spherical, while some are squashed or stretched spheres (discus / rugby ball shape). An octupole shape is something like a pear shape, with on end fatter than the other. This is a rare thing in nuclei as a more symmetric shape is generally the lower energy configuration, and thus more favoured. When we see octupole shapes we can try to deduce something about the reasons why it exists.

In the work, nuclear theorists from the Surrey group, and elsewhere, made use of a selection of state of the art nuclear models to see how the observed properties corresponded to underlying structure, figuring out how the particular behaviour of protons and neutrons in the nucleus leads to the octupole shape being favoured, and the details of the way the nucleons carry angular momentum inside the nucleus seems to be the answer.

Here’s a visualisation of a typical octupole-deformed shape such as found in the nuclei in the recent paper