Only a short post this week, as I’m attending the first European conference on Learning & Teaching in Politics, IR and European Studies at the University of Maastricht (yes, there again).

Obviously this week potentially represents an important moment for the EU, with its possible resolution of the Spitzenkandidat issue at Ypres. Certainly, to listen to some of the British press, the meeting will be almost on a par with the trench warfare of World War I and is likely to lead to a British exit.

That is overblown and unhelpful to all involved. Commission presidents remain limited in their powers; the Commission only proposes legislation; and none of the alternative people being touted for the role are particularly inspiring replacements, partly because member states don’t want a dynamic person in the role. As Kurt Koller pointed out, if Juncker (or Schulz) was going to be such a problem, why didn’t the UK make much more of a fuss when the whole idea of Spitzenkandidaten was launched?

But this is something we will come back too, since whatever happens tomorrow, the results will be a matter of debate.

Although writing this brings me back to the point I would like to consider here, namely the difficulty of maintaining momentum for eurosceptics.

You might recall that eurosceptics did really well in the European elections: of course you do.

You’ll also be aware that they have had difficulty in forming groups: EAF has failed in the past week, EFD has become EFDD, while ECR has been the best of the bunch, becoming the third largest group in the EP.

But aside from this, sceptics have not kept the profile they had at the time of the elections.

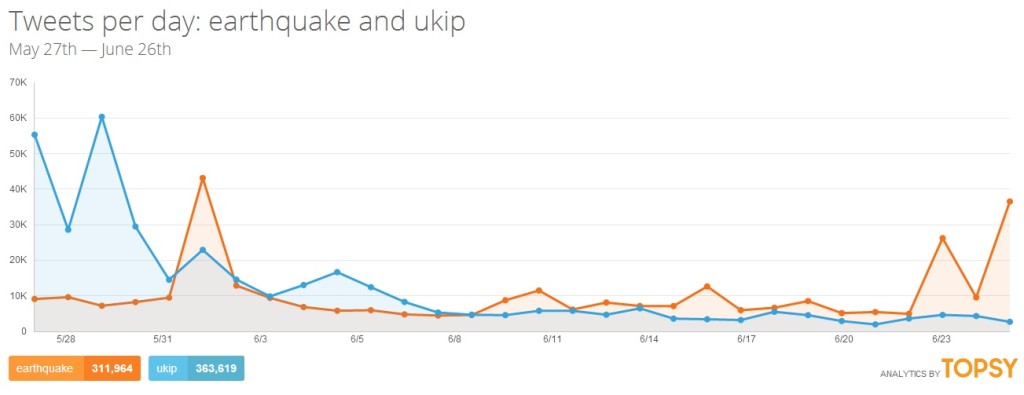

Consider the case of UKIP. In the campaigning phase, all the talk was of causing a political earthquake. For my own personal amusement, I started watching Topsy to compare mentions of ‘UKIP’ and ‘earthquake’: the data for the past month is instructive:

Google Trends shows a similar pattern: a big peak, followed by a rapid drop-off of interest.

This suggests that UKIP, and other sceptics, remain in a marginal political position, able to benefit from particular moments, but not able to make the political weather and enjoy a high structural level of media and popular interest.

As I’ve noted before, this is potentially the killer for UKIP, especially once the 2015 general election has come and gone – the opportunities for opportunism look a bit thin on the ground.

To tie this all up, the continuing failure of British EU policy by Cameron – Juncker, AfD joining the ECR, etc – will mean that UKIP has an easier time of things: if the Conservatives could find a more constructive approach, they might find that they could kill two birds with one stone.