As we head into a short Easter break, it’s useful to review the state of play in the social media campaigning around the EU referendum. While the absence of movement in the polling suggests that wider public interest remains to be fully engaged, the period since February has been vital on both sides.

The closing of the European Council deal last month meant that David Cameron could start to campaign actively on the benefits of membership, as could the rest of the senior Tory party figures and indeed the Labour party, even if the latter has been noted more by its absence than anything else. This sorting of the main political figures has also meant that messages can be practised and honed, and local activists recruited and trained.

Social media has been an important part of this process. However, we hesitate to say that this is a ‘social media referendum’, both because such claims have been made and disproved many times before and because we see no clear example of things having changed so far. At the same time, we know that eurosceptics have long used cyberspace as a forum for contact and exchange of ideas, and so have a well-established presence on which to draw. In addition, the nature of a referendum vote somewhat upsets the conventional, constituency-based campaigning of a general election: any vote, anywhere in the country is equally useful, so social media has an additive quality that is usually missing.

Since we began our surveying in early February, several trends have become clear.

Firstly, Twitter is used in very different ways by different groups.

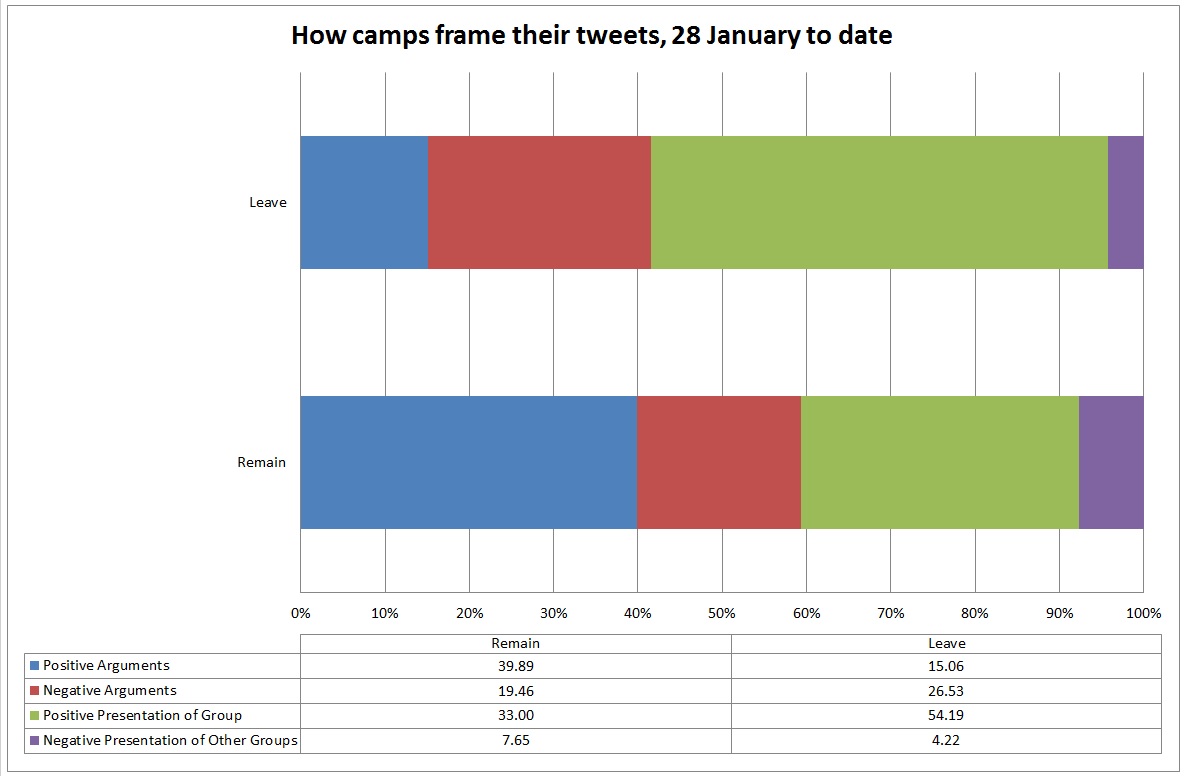

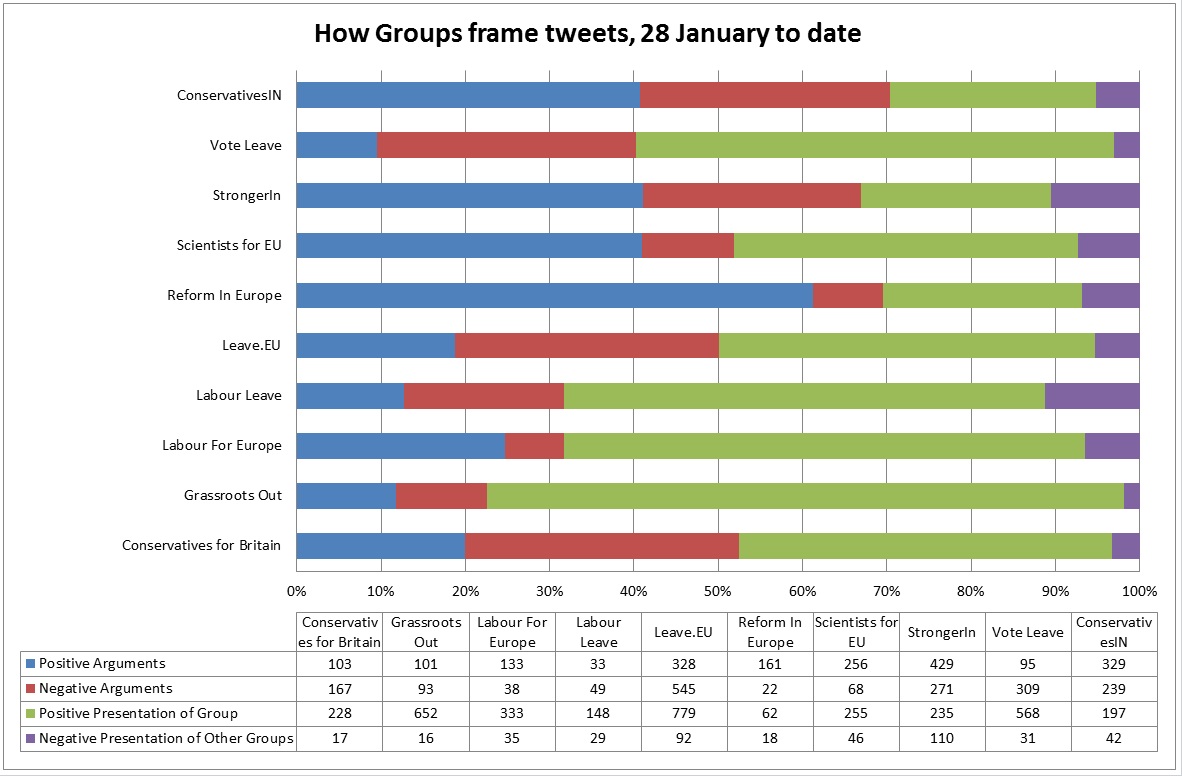

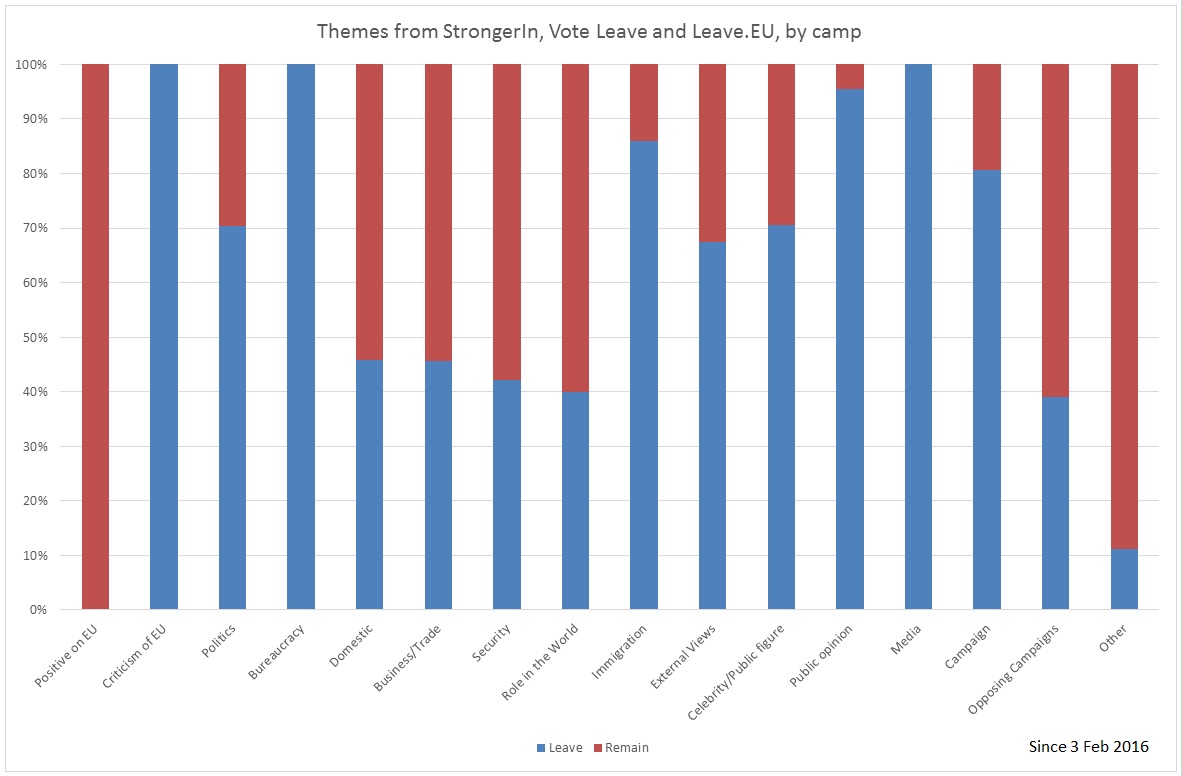

Broadly speaking, Remain groups have been much more focused on making positive arguments about the value of membership, while Leave groups have focused more on membership’s costs and problems. Just as importantly, Leave groups have used Twitter as a vehicle for community-building and -maintenance, devoting many tweets to connecting with local campaigning and other groups, whereas Remain groups have done this much less. In part, this is also a reflection of the much larger base that Leave have to work with (approximately 3.5 times as many followers, with Leave.EU alone having twice as many followers as all the Remain groups in our sample): if we make the assumption that this reflects offline mobilisation, then there are simply more Leave activists and activities to share.

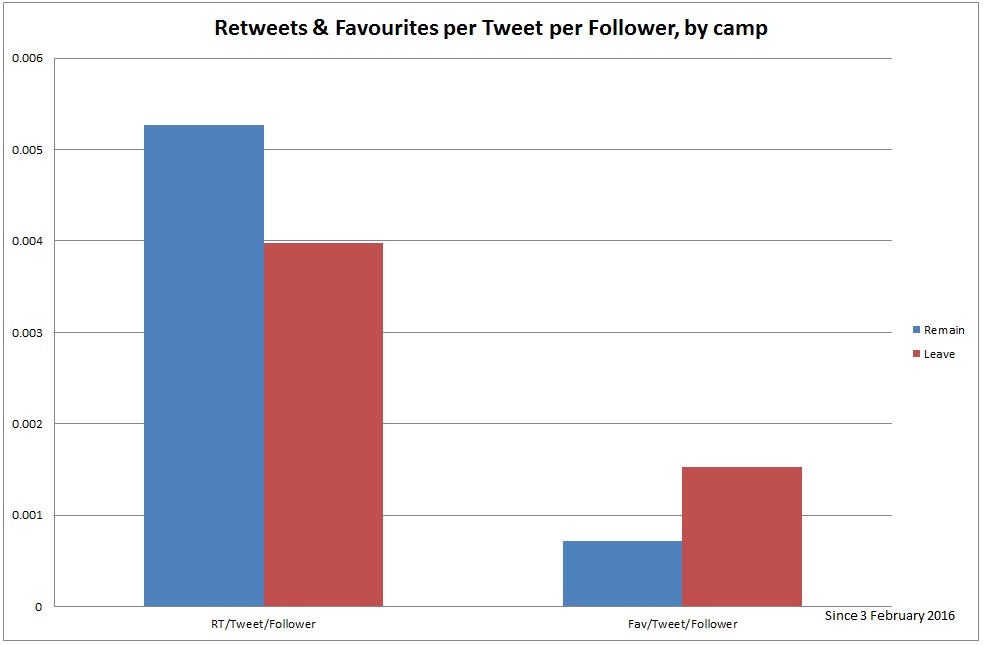

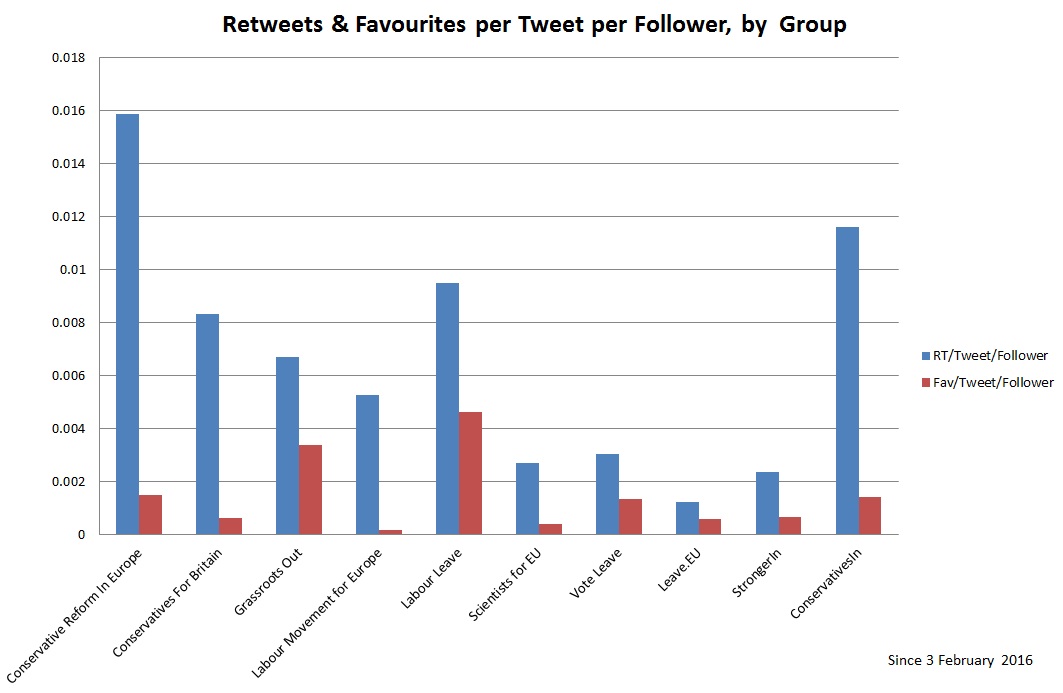

But if Leave dominate the space, then it is also important to note that Remain have appeared to be more successful in spreading their messages: their relatively higher level of retweets that we noted several weeks ago has been maintained.

The reasons for this difference are not entirely clear, but two possibilities are worth considering. Firstly, it is clear that more niche groups are much more likely to get retweets than the broader campaigns: the former have a more coherent audience, which in turn makes it more likely that material will be worth sharing. As such, this might be more of a statistical artefact than anything else, especially given the weight of Leave.EU in the calculations: this will become more evident once official designations are made. Secondly, there is something to be said for the argument that Remain arguments are shared more because they are more novel: Leave have drawn on two decades’ worth of campaigning, so much of what they say has been said many times before, whereas the logics for staying in the EU are much less well known. If that is the case, then we might expect this effect to taper off during the rest of the campaign.

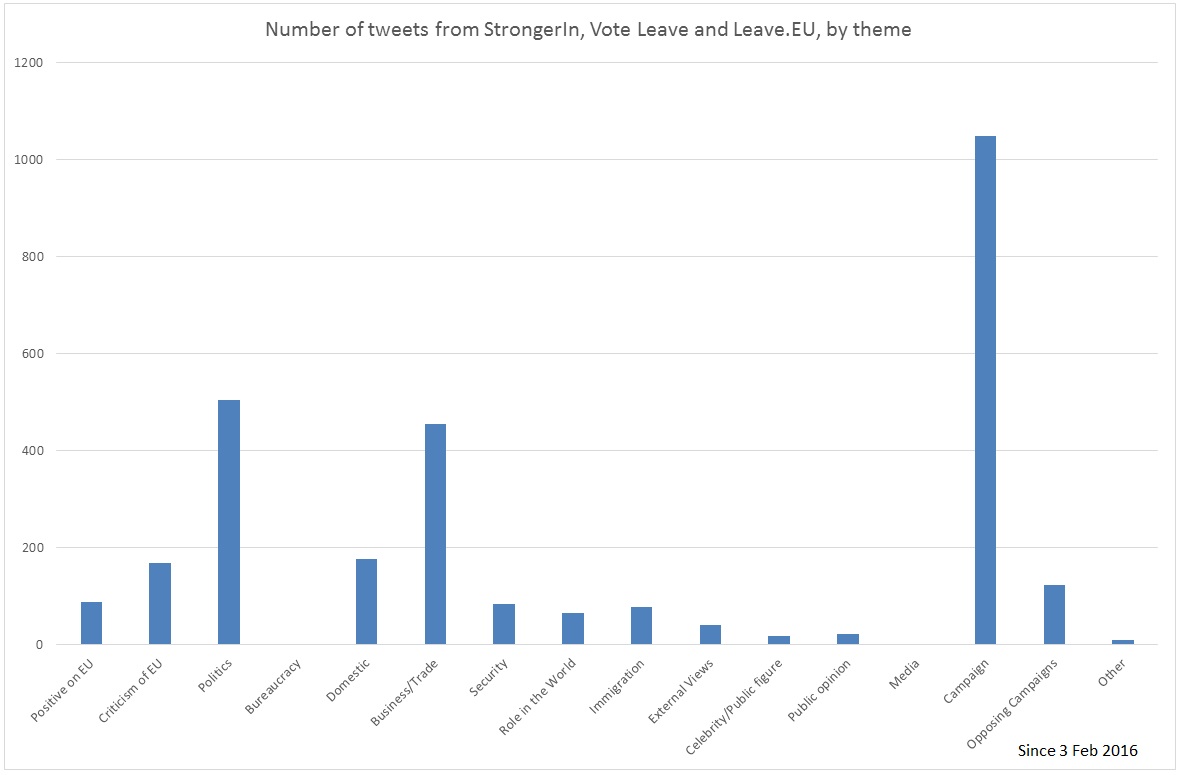

If we look at themes, then we can see some of these issues coming through in different ways. Our coding of the main groups – Leave.EU, StrongerIn and Vote Leave – shows that they all spend much time talking about campaigning activity, but then have multiple core areas in their lines of communication. The two Leave groups talk often about politics (including Cameron’s deal), while StrongerIn is big on business and trade. Immigration has not been a frequent topic to date, but when it has been raised, then it has usually been on the Leave side. Cameron’s preferred frame, of ‘security’ has made some headway with StrongerIn, but remains rather marginal.

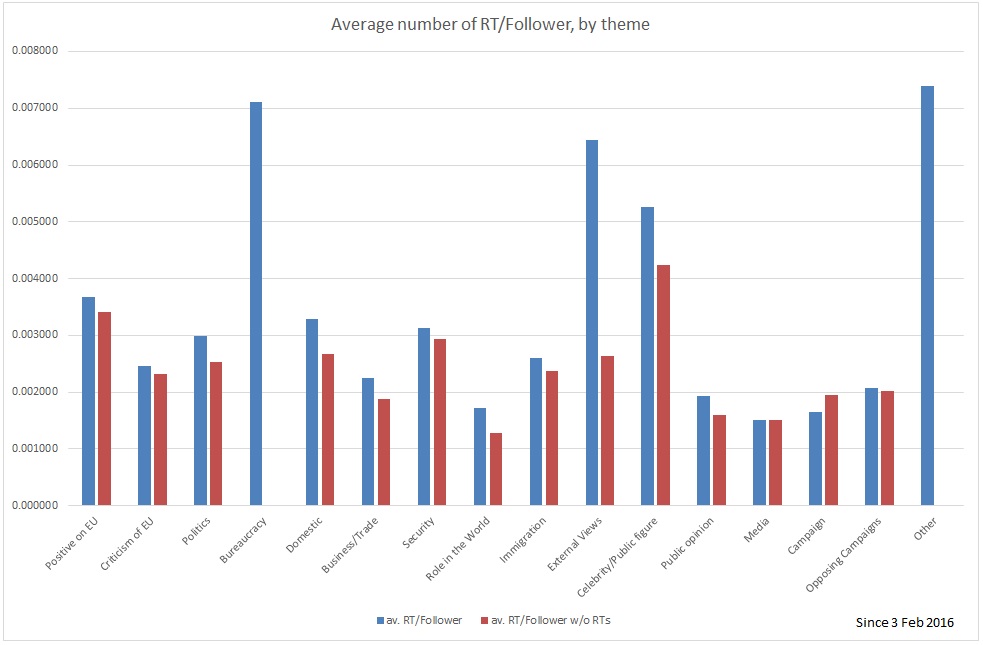

Interestingly, the choice of theme doesn’t seem to have a big impact on its impact, as measured by retweets. Our graph below is less varied than it might first appear, as all the peaks in retweeting are for very small numbers of tweets, which means we should treat them with a considerable degree of caution, especially the celebrity/public figure endorsements. Tellingly, the other theme where groups’ original tweets (as opposed to tweets from others which they have then retweeted) are more retweeted than average is in ‘campaigning’, which suggests that these groups operate to some degree as clearing houses for content produced elsewhere, which underlines our original intent to study these groups as key points in the social media space.

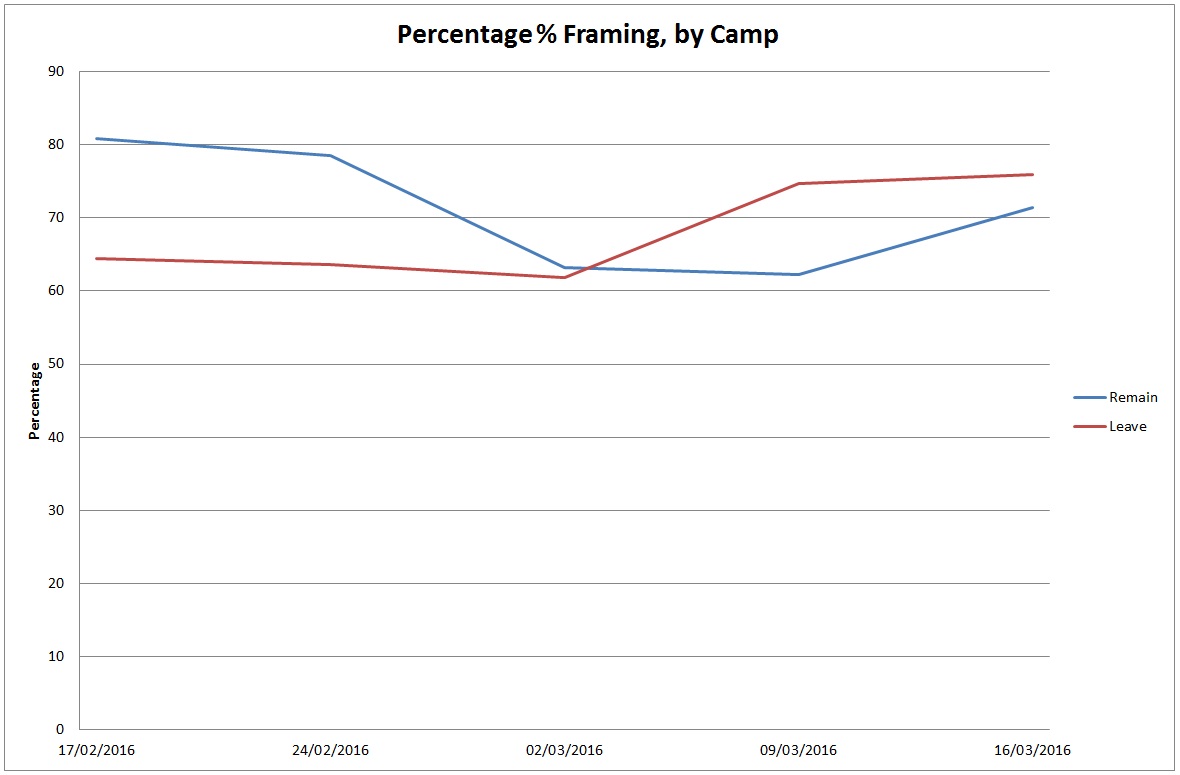

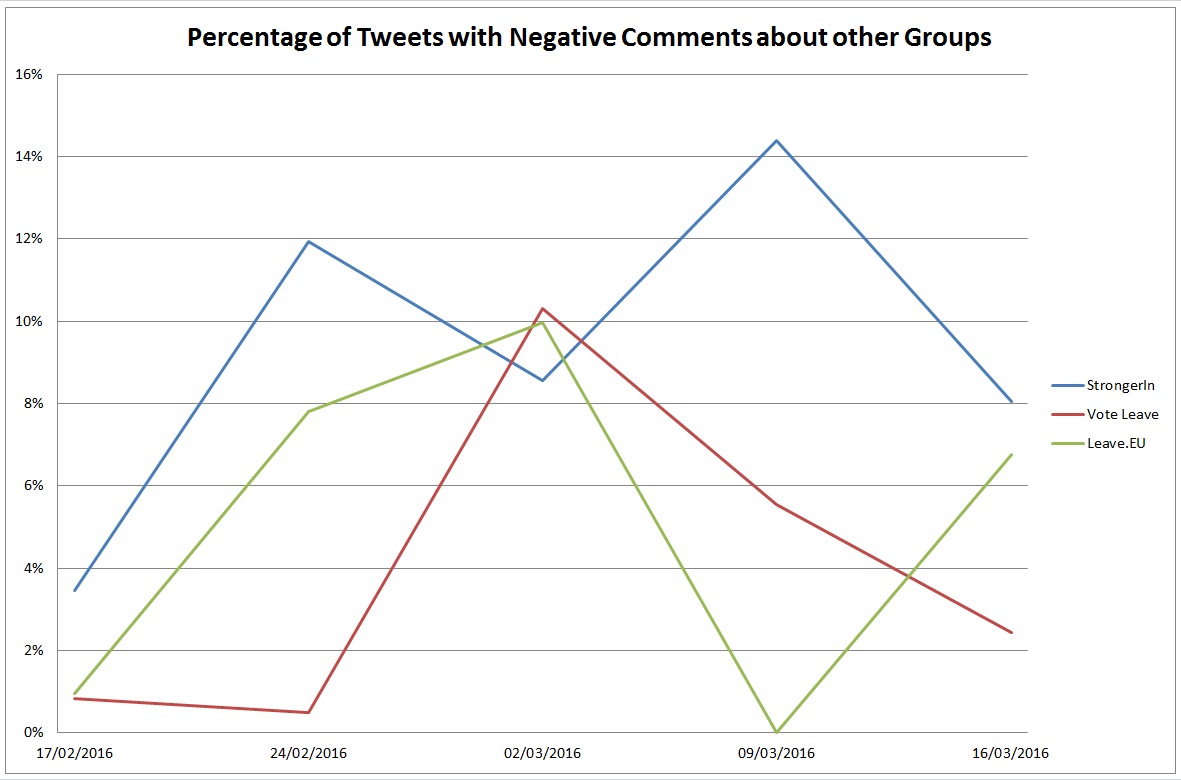

Finally, groups have appeared to maintain their generally positive framing of messages so far: almost three-quarters of tweets now have positive messages about arguments or about the group, and negative comments about other groups remain rare (if not necessarily mild in tone). Again, while this has held during this phase, the critical moment will come with the opening of the official campaign period.

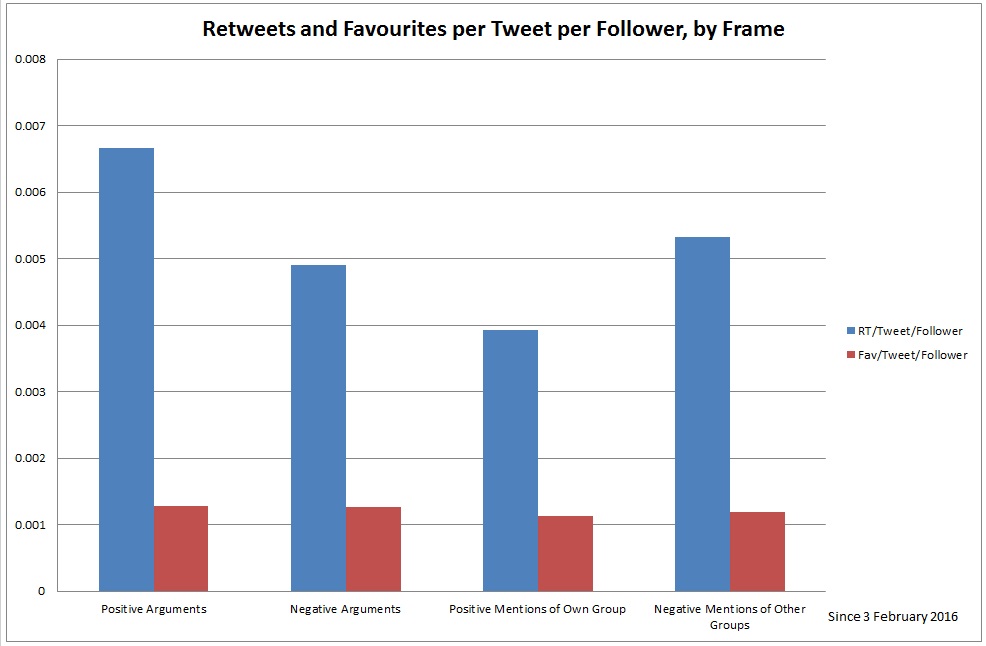

The relative success of positive arguments in being shared continues: such tweets are clearly more likely to be shared than any other, with negatively-framed tweets coming in ahead of positive mentions about one’s own group. While the latter is not surprising – these tweets are either lacking in substantive content or are of interest to a narrow audience (the “we’re loving campaigning in rainy market town” type) – the relative success of positive arguments is less easily explained. We know that such tweets are more likely to come from Remain groups, so once again the novelty argument outlined above might be at play.

The overall picture is thus more nuanced than it might first appear. Both sides might take some comfort from our findings, but equally the situation is still a deeply contingent one, liable to disruption from external events. When we return in a fortnight, we’ll be able to look at the impact of the Brussels attacks, which present the first major event that sits outside of the EU per se, but which has been connected back into the referendum discussion: the restraint shown around last week’s discussion of the Queen might well not hold.