So here we are, about a month into the new government. How’s it shaping up with the EU referendum thing? For me, four things stick out so far.

So here we are, about a month into the new government. How’s it shaping up with the EU referendum thing? For me, four things stick out so far.

Firstly, David Cameron has conformed to type in his approach to the matter. Assuming that he was a surprised as the next man (that next man being Ed Miliband) to win the election, he has set about things in as pragmatic a manner as possible. That has meant some dashing between continental capitals to sound out/reassure/lobby (in that order) key interlocutors; tying in key sceptics into the negotiation team (most obviously Hammond, May and Osborne) and generally trying to keep a lid on things. The unexpected nature of his electoral victory has given Cameron a (very) brief window of opportunity with his party, and he’s using that to full effect, not dawdling on negotiations.

The obvious trade-off is that Cameron still doesn’t have a good idea of what he can achieve or ‘win’. The continued absence of a clear agenda of policy points strongly reinforces the impression that he’s biddable on most things. As the useful Cicero Group summary showed, much of what has been discussed is actually a matter for HMG itself to do, rather than any change in EU treaties or legislation: likewise, the continuing muddle about the ECHR doesn’t give great confidence that anyone in Number 10 is building a constructive agenda of work. This despite the arrival of Mats Persson of Open Europe as Cameron’s special advisor, a level-headed if critical voice.

This feeds into the second point, namely that the UK continues to navel-gaze. The debate so far has been very largely about getting something for the UK out of this, and how ‘Europe’ might try to stifle (or, more rarely, help) that. Almost completely absent have been frames of making things better for the whole EU: Cameron’s comments in Riga a couple of weeks ago suggest the tone. For Cameron, his negotiation team and most of his party, this will be not only presented as ‘us’ against ‘them’, but pursued as such.

Where the more constructive/engaged frame has emerged (as here) it has come from the few pro-EU voices to have put their head above the parapet. This is, in of itself, something to note, since there was a widespread assumption that it would take an actual referendum for the pro campaign to stir itself. Fair to say that neither side has really got going yet (this, this, this, this and this as a small sample) in part because of the uncertainty about what’s happening with the renegotiation element and in part because of the obvious personality politics involved.

The third observation is that the election itself continues to exert an influence on matters. Labour and the LibDems are busy regrouping and lack leadership to challenge Cameron’s plan; Cameron’s enhanced position vis-a-vis his backbench has already been noted; and the SNP are finding that more MPs doesn’t really help when they have little to leverage against the government. Most interesting (for me, at least) has been the winding in of UKIP in the aftermath of the Farage (un)resignation: without his presence in public, the party has lost a lot of the profile it had in the media pre-election. A quick check of their website shows they are still pumped out content and comment, but without much pick up. the Blatter/Farage comparisons also suggest that the latter has suffered at least some damage to his teflon reputation.

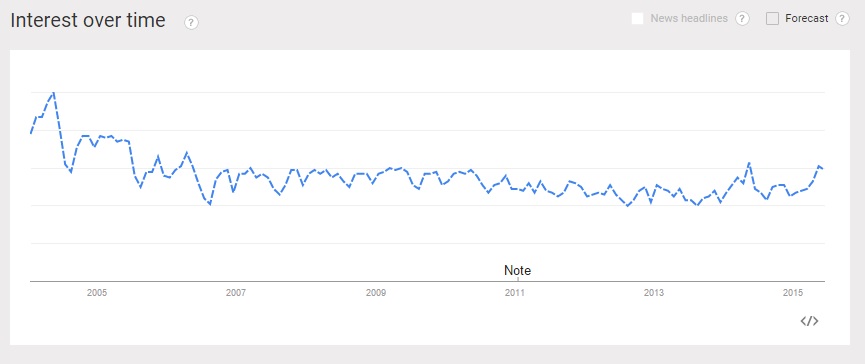

And so, finally, to the continuing apathy of most people, something that has been deeply palpable. There’s some evidence of a recent upswing of interest, as the chart from Google Trends (below) shows, but only back to the sort of level seen in the aftermath of the Constitutional Treaty a decade ago: far from the burning, predominant issue it sometimes is presented as. More anecdotally, there isn’t a sense of febrile political debate on the subject in the street and in the pubs of the country: it’s certainly more AV referendum than Scottish independence referendum to date.

Added to this, we have more polling evidence (insert witty observation about reliability issues here) that the British public is increasingly supportive of EU membership, and it’s as clear as ever that this referendum – when it does come and pretty much regardless of its content – will solve little of the underlying problems. Already, critical voices talk of a second vote, or of a set-up. Unless the renegotiation agenda firms up, and a more meaningful public debate develops, this is unlikely to be anything more than a costly diversion from the serious issues facing both the EU and the UK.