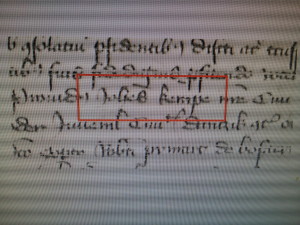

Gdańsk, Archiwum Państwowe, APG 300, 27/3, fol. 12r. Akta miasta Gdańska – Missiva, 12 June 1431.

Margery Kempe’s arrival in the modern world was surprisingly quiet. In 1910, Edmund Gardner published a brief account of the East Anglian mystic as printed in 1521 by Henry Pepwall – itself a reprint of a 1501 pamphlet by Wynkyn de Worde. Garner exaggerated Kempe’s reputation for mysticism and assumed that she was an unmarried woman living in the 1290s, a certain ‘Margeria filia Johannis Kempe’ [Margery, daughter of John Kempe] found in a record from Canterbury. His conjectures were aided by the claim of his early modern printed source that Kempe had been an anchoress, a person permanently walled in in a cell attached to a church or bridge – dead to the world. A year later, the novelist and latter-day mystic Evelyn Underhill proclaimed Kempe ‘the first English mystic we can name with certainty’. And so the early twentieth century invented a saintly thirteenth-century virgin mystic and spiritual pioneer.

All this was turned on its head when in 1934 the only known manuscript of Margery Kempe’s Book was discovered in the ping-pong cupboard of a house belonging to the Catholic Butler-Bowden family. On 30 September 1934, Lieutenant-Colonel William Butler-Bowden nonchalantly announced the find in The Times, claiming that occasionally ‘visitors read a page or two of [the manuscript]’. (His son later recalled how Butler-Bowden had threatened to dispose of this manuscript and other nearby clutter: ‘I am going to put this whole “–––“ lot on the bonfire tomorrow and then we may be able to find Ping Pong balls & bats when we want them’.) The American scholar Hope Emily Allen identified the manuscript, and her article in The Times of 27 December 1934 marks the ‘academic’ discovery of this text.

Margery Kempe, it emerged, was no saintly ‘Margeria’: instead of exhuming the immured virgin foundress of English mysticism, The Book of Margery Kempe reveals a fifteenth-century mother of fourteen whose notorious weeping and screaming in public places made her an international embarrassment – as one early reviewer writes, ‘it would have been wonderful to have met her on the bus’. But just how much of Margery’s eccentric character was shaped by the author Kempe? To many readers The Book of Margery Kempe is not necessarily Margery Kempe’s book: her main competitor for the title of ‘author’ is the priest who acted as her main scribe, in all likelihood her confessor Robert Springold. The Book is shot through with his learning and theological training, making it at times difficult to hear Kempe’s voice.

Some time ago, I decided to look for Margery Kempe’s eldest son. He is believed to have been the Book’s first scribe before his draft was rewritten by Springold. Gdańsk, where Kempe’s son lived and worked, struck me as an obvious starting place. Despite the city’s turbulent history, surviving copies of the town council’s outgoing letters reach as far back as the early fifteenth century. It wasn’t long before I stumbled over a Latin letter, issued on 12 June 1431 to one John Kempe (the find has been covered by The Guardian on 8 May 2015). The letter requests the English authorities to assist Kempe in recovering a substantial sum from a Boston merchant. Given the date and circumstances, there can be little doubt that John Kempe was Margery’s eldest son (his father and grandfather were also called John). But what makes this discovery so exciting is that it confirms crucial dates and events in the Book, lending authority to some of Margery Kempe’s claims while questioning Springold’s account of how the book was written. What’s more, the letter strengthens John’s identification with the first scribe. In my subsequent research I found new evidence for Springold’s involvement with Margery Kempe’s family – all of which allows us to see Margery Kempe as the Book’s author rather than as Springold’s co-author.

The Book of Margery Kempe has enriched our understanding of early English prose, popular piety, women’s religious culture, and the genre of autobiography. But Margery Kempe has also helped to make gender a much bigger part of our discussions about the medieval canon, boosting the voice of literary women, from the historical Julian of Norwich to Chaucer’s fictional Wife of Bath. These findings embed the Book more firmly in its historical context and, crucially, help us once more to rediscover Margery Kempe, only this time as the authoritative voice behind her text.

My discussion of these findings will appear as “The writyng of this tretys”: Margery Kempe’s Son and the Authorship of Her Book’ in volume 37 of Studies of the Age of Chaucer.

Professor of Medieval Literature and Culture

Department of English, University of Groningen