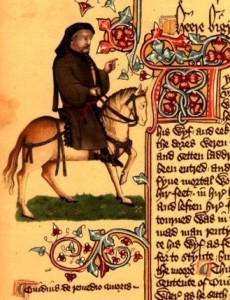

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ellesmere_Chaucer#/media/File:Chaucer_ellesmere.jpg

My first experience of reading medieval literature, unsurprisingly, came in the form of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales composed in the fourteenth-century. In 2009, as part of my A-Level course in English Literature I studied The Nun’s Priest’s Tale and immediately became interested in Middle English literature and medieval history. However, it would be another three years and a degree later before I encountered Marie de France for the first time and began to comprehend the significance of her influence on the medieval canon.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Marie_de_France#/media/File:Marie_de_France_1.tif

Marie de France is an enigmatic figure and very little is known about her identity. However, there is a general consensus that she was a French woman who resided at the English court of Henry II during the late twelfth-century. She is attributed with writing three major works in Old French, a collection of short narrative poems known as the Lais, a collection of humorous fables, and the Legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick.

While there is no direct evidence that Chaucer read Marie’s works, there are some striking similarities between the writings of both that illustrate the impact that Marie had on later medieval literature. One example (of many) that demonstrates this influence is The Nun’s Priest’s Tale itself. The Tale tells the story of a cock named Chauntecleer who dreams of a ‘beest’ that wants him dead. Shortly after this dream he encounters a fox who through flattery encourages him to sing with his eyes closed and his neck outstretched. Chauntecleer obliges him and is seized by the fox. He only escapes by tricking the fox into opening his mouth, allowing Chauntecleer to fly away to a nearby tree. This is an expanded, elaborate version of a fable retold by Marie, ‘The Cock and the Fox’ where the fox captures the cock through flattery by convincing him to sing with his eyes closed. The cock then outsmarts the fox by tricking him into opening his mouth, allowing the cock to take refuge in a tall tree.

In preparation for writing this blogpost, I eagerly dug out my original copy of The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, confident that I would find Marie’s name at the back of the book where the genre of the beast fable is discussed. I was mistaken. The appendix contains extracts from the ancient writers Cicero and Aesop and a summary of the later French epic fable The Romance of Reynard the Fox but Marie’s version of the fable is omitted entirely. This indicates the ease with which her significance is overlooked and highlights the importance of rethinking women’s role and engagement with the medieval canon.

Marie’s role as a female writer, while interesting, is not the main focus of my PhD research. Instead, I draw on queer theory to analyse queer time and space in two of her Lais, Bisclavret and Lanval, alongside the more well-known medieval texts Sir Orfeo, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath’s Tale. When viewed alongside these later texts, it becomes apparent that Marie’s Lais draw on the same themes, motifs and courtly narratives that dominate medieval writing. It is therefore about time that her contribution to literature is brought to the fore and she is given the recognition afforded to medieval male writers such as Chaucer and the anonymous but presumed male authors of texts such as Sir Orfeo and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.