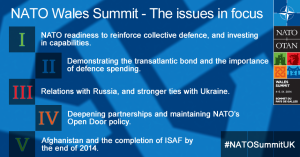

In the run up to NATO’s Summit in Wales (September 4th to 5th) I will be blogging on issues related to the future of the Alliance, with a particular focus on the place of UNSCR 1325 on women, peace and security on the agenda. This is my first blog on the topic.

The importance of NATO’s Wales Summit for the future of the Alliance has been much discussed (here, here and here). However, what much of this coverage has overlooked is the significance of the Summit for the place of UNSCR 1325 on NATO’s agenda.

UNSCR 1325 has gained significant momentum and traction on NATO’s agenda since the Chicago Summit two years ago. The appointment of the Secretary General’s Special Representative on Women, Peace and Security has been instrumental in this drive. This year alone has seen NATO hold its first ever consultation with civil society (on any issue) in respect of the latest NATO Action Plan on UNSCR 1325. The Action Plan was subsequently made public (opening it up for scrutiny for the first time) and followed on from the release of an updated NATO/EAPC policy on UNSCR 1325.

The creation of the Special Representative position at the Chicago Summit was significant but would not have had any lasting impact had Norway not funded the position and appointed Mari Skåre to the post for two years. The future of the positon has already been secured ahead of the summit, with the positon becoming a permanent fixture in the International Staff (on a 3+3 year contract in line with all new International Staff). This is no small achievement given the considerable budgetary constraints placed upon NATO, which have resulted in an International Staff comparable in size to that at the end of the Cold War when NATO members numbered half of the current Allies.

The agenda for NATO Wales includes ‘women, peace and security’ under the final item for discussion – Afghanistan. Afghanistan has had a central role in NATO’s understanding of UNSCR 1325. The gendered specificities of the ISAF mission have provided NATO with a context from which to interpret the Resolution. This has had implications for the way in which NATO has sought to implement the Resolution. Primarily, we have seen NATO’s longstanding preoccupation with the status of women in NATO forces[i] folded under the UNSCR 1325 banner. We have also seen gender instrumentalised as a tool to increase operational effectiveness, most noticeably with the use of Female Engagement Teams (FETs).

The significance of including women, peace and security formally on the agenda of the Wales Summit should not be underestimated. Symbolically, it is the last item for discussion but nevertheless the Summit provides a critical juncture for NATO to recommit to the agenda. It remains to be seen what form this commitment will take as NATO’s involvement in Afghanistan changes form.

More to follow on this here and here

[i] The Committee on the Status of Women in NATO Forces (CWINF) was established in the 1960s. Feminist work has demonstrated the link between recruitment of women into the armed forces and a ‘manpower’ shortfall, for example due to the end of conscription or a declining birth rate (see: Segal, 1995 and Enloe 2007).